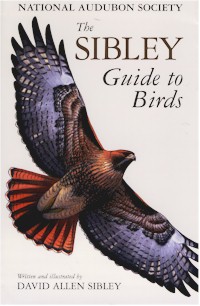

If a contemporary heir can lay claim to John James Audubon’s legacy as a bird artist, it is David Allen Sibley. Four years ago, The Sibley Guide to Birds was published to immediate and widespread acclaim, with many bird watchers calling it the most important advance since Roger Tory Peterson’s Field Guide to the Birds in 1934. Sibley spent two decades painting all 810 North American bird species, producing 6600 illustrations. With the publication of Duff Hart-Davis’ Audubon’s Elephant approaching, I wondered how this modern bird artist viewed his 18th-century predecessor. When I called, David Sibley was reading a proof copy of the Audubon book.

DS: I started thinking at a very young age that I would paint birds for a living, and I started thinking about doing a book when I was 12 or 13. The idea of doing a field guide to all the birds of North America didn’t really take shape until about 1987. At that point, I had spent seven years, from 1980 to 1987, just traveling around the country living very cheaply in a camper van, watching birds and drawing. In 1987, I committed to doing the book. I spent six years working on it before I found a publisher.

Yes, I decided that all of this drawing and studying I had been doing should continue, and I should focus on putting this book together. I did that for about six years and then I found a publisher when I felt I was ready to start working on the final draft. Then another six years elapsed before the book came out with me sitting in the studio doing the paintings—a total of 18 or 20 years of traveling, studying, working. I’ve talked a number of times about that sharp transition in my life from the years of just wandering around in the woods spending almost every day from dawn to dusk outdoors, to working just in the studio, painting. And in the last few years, I’ve been traveling around the country being a promoter, lecturer and author.

I did, yes. I underlined a couple of quotes in Audubon’s Elephant. There’s one where he writes to a friend, “I am thrown into a vortex of business that I never conceived I could manage.” After years in the woods looking at birds, he had to become a publisher, a businessman and all of that stuff. I felt a lot of empathy for that.

I actually didn’t pay that much attention to Audubon until after my own book came out. I started reading his journals, and I’ve gotten really interested in his life and experiences. His journals are such a fascinating depiction of life at that time. But he wrote about his style of drawing birds, the way he wrote about it, the way he described it, and the things he said about how he developed the idea for The Birds of America sounded so familiar. It really struck me that Audubon’s motivation for doing these giant paintings of birds was really just like lots of other people I know and me—it was just a desire to share it.

Audubon’s name is well known and very big in birding, of course, now synonymous with bird conservation of the Audubon Societies, but his work is not referred to much by modern birders. It’s a bit dated, not surprisingly, being almost 200 years old, and the poses and arrangements of the birds look a little contrived by modern standards. His self-proclaimed goal was to introduce the birds of America to a wide audience, and he used some very dramatic scenes to catch the viewer’s attention. So his work was part-scientific documentation and part-fine art. His work was a huge leap forward from the much stiffer and unemotional work of previous artists, and later artists learned from and built on his success to show birds in more true-to-life scenes and postures. But for capturing the spirit of the birds and their elemental struggle to survive, with a genuineness and clear love of the birds and sensitivity to the delicate details of feathers, he has no equal.