Pessimism is the only truly relevant consciousness: negativity is vastly more reliable than optimism can ever aspire to be. My purpose here is to spread fear and despair, so for those of you in need of a more upbeat diversion, please move on.

Any slice of popular culture is by its very nature transient. Few things enjoy widespread popularity indefinitely; the never-ending human requirement for new entertainment fuels the hurried extinction of yesterday’s delights, in a perpetual litany of “out with the old, in with the new.” An argument over what constitutes an acceptable or commendable reign as a pop icon is beyond the scope of this piece.

But a gnawing, late-night fear is worming its way into a small segment of the collectables maelstrom and a fate not shared by many other accumulators of stuff; that is, that the collectors themselves will outlive market interest in their hobby.

The great pulp magazines, one of America’s least-known, most poorly respected champions of printed achievement, stand on the brink of complete extinction. The thunderous silence regarding their possible disappearance brings sorrow to the handful of the faithful still reveling in their browning glory. This is not, however, intended as a defense of the collectability of these magazines, although aspects of their historical and cultural importance are touched upon. Rather, it is intended as a call to awareness that the last nails of the coffin already may have been driven.

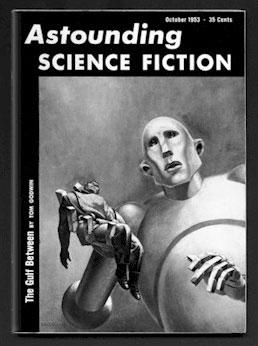

Briefly, for those of you unfamiliar with the physical format of the pulp magazines, they are approximately 7 inches by 10 inches overall, anywhere from a quarter- to a half-inch thick, with a color cover on coated paper, and interior pages made of highly acidic pulpwood paper. Hence the term of endearment, pulps. The cover is slightly larger than the interior and hangs over the edges, which protected the pages at inception, but tends to become ragged later. A typical issue runs to 128 numbered pages inside, usually printed in 16- or 32-page signatures. These are then stapled from top to bottom about a quarter inch from the spine to which the cover is glued. The weekly, monthly or quarterly print runs of the hundreds of different titles would stagger most publishers today. Interiors are typically two columns of text, with occasional line drawings; the color covers emphasize boldness and action. Modestly priced even in the Depression at anywhere from five to 25 cents a copy, a pulp magazine offered a few hours of preciously achievable escapism.

The first true pulp is generally believed to have foisted itself onto the public in October 1896, when Argosy switched to an all-fiction format. The pulps reigned supreme on the newsstands, at least in terms of volume, from the early 1900s to their demise in the mid 50s. The 1920s to 1940s are considered their Golden Age.

The pulps, rough hewn, cheaply printed, hurriedly written and quickly forgotten, hold a fascinating place in the history of the printed word, whether the literati like it or not. Indeed, a tremendous volume of badly written, poorly produced material lies within their pages deserving the scorn associated with the now-derogatory term pulp fiction. Their highly acidic paper and carelessly overhanging covers have largely fared quite badly over the decades, making most of the few remaining copies aesthetically unappealing. Neatness does count. So their final demise may, in fact, be applauded in certain circles by those scoffers who vilify the names of the giants that trod their pages; Edgar Rice Burroughs, Robert E. Howard, Dashiell Hammett, H.P. Lovecraft and more. Mixed among the forgettable and the regrettable are indeed many great writers of imaginative fiction. To dismiss the entire pulp era as crap is to miss some tremendously imaginative writing and art, but again, an attempt at persuasion to accept the pulps is not the purpose here.

This about extinction. The pulps may be disappearing while your choice of collectable probably isn’t.

Several factors deter neophytes and veterans alike from collecting the original magazines, even presupposing that one is inclined to do so. The basic difficulty of finding them, when a whopping percentage of the population stares blankly at their mention, doesn’t make matters any easier. How readily do venerable pulp titles such as Blue Book, Adventure and Black Mask leap to mind today? Flea markets, antique shows, church bazaars and crumbling attics are yielding scant few treasures in these modern times. Bear in mind that the last of the true pulps—before the digest format took over—exited the newsstands by the mid-50s, now a half century since their demise. The bulk of the survivors in digest format are science fiction magazines, such as Astounding, and these 19501960 issues are not widely collected today. Added to that is the difficulty of stumbling across copies in decent to upper grades. The overhanging covers frequently succumb to tears, promoting the loss of small-to-gargantuan pieces. The highly acidic paper can change to a color any tanning enthusiast would admire. This browning, often brittle, paper can make handling precarious, and casual reading nigh impossible. It may even inspire a celebratory round of vacuuming as flaking edges shower the reader with affectionate epidermis.

Old paper also holds a certain fascination for various insects, rodents and other lower creatures of the food chain who frequently gnaw into oblivion yet another copy of something dear. A particularly worm-ridden first issue of Uncanny led one dealer to consider discounting the book because it was considerably lighter than most copies. And for inexplicable reasons, hosts of previous owners found margins and other open areas an irresistible artistic lure for pen and ink, naturally! Many copies have math sums, various unworthy notations and names written as if in practice, further diminishing their desirability. While she is quite likely long deceased or very elderly, Mrs. Mary T_______ has much to answer for, repeatedly inscribing her married name and thus despoiling the back cover of an early issue of The Shadow. Her frequent underlining of Mrs., while perhaps of emotional significance to her, did nothing to augment the collectability of that particular item.

In recent years, many of the more sought-after pulps have scaled upward in price, an unappealing trend following decades of affordability. The fondly remembered days when stacks of Doc Savage Magazine, Dime Detective and others idled around used bookstores at outrageously inexpensive prices are now long gone. Serialized stories, a mainstay of Weird Tales and other titles in their day, are the bane of collecting existence now. Try piecing together five or more installments of a weekly or monthly magazine on the stands a decade before the attack on Pearl Harbor. The dated nature of the writing, both in style as well as content, also contributes to their lack of contemporary appeal, and for neophytes, it’s a stretch to picture an era before the Internet, satellite TV or cell phones. Try explaining to people today why our hero is desperately searching for a drugstore to make a phone call. And in case anyone is pondering its origins, political incorrectness was practically invented by the pulps. The Spicy titles especially are a haven for all things currently unacceptable.

These magazines were written in a less sophisticated era, where access to information was far more limited than today. Africa and the Orient were worlds away, and the mind-boggling rituals that surely occurred there were anybody’s guess. The Wild West was only a generation back, but cheerfully inaccurate tales of its glorified wonders were accepted as fact. Other planets teemed with bug-eyed aliens with enormous craniums bent solely on Earth’s destruction or the wholesale kidnapping of its women. Everyone who read Amazing Stories in the 1920s knew it was true. Now, these viewpoints seem almost comical, and yet millions of people delighted in entertaining tales of everything from high adventure to impossible romance.

The typical pulp hero is usually a person of noble character, unshakable virtue and morality and a pinnacle of human achievement that would have contemporary audiences howling with derisive laughter. Self sacrifice, white-hat goodness, and chaste male/female relationships of undying celibate love would wash over most readers today leaving no greater impression than a small unsightly stain. While indeed more “realistic” representations of the human condition can be found within their pages, the pulps liked their heroes heroic, untarnished and undefeated.

Unfortunately, this lodestone of declining condition and outdated prose doesn’t help secure future enthusiasm in a collectable. While pulp acquisition as a pastime has ebbed and flowed, the community has never been enormous and the generation of collectors free of liver spots is not taking up the torch.

While collectors keep kicking the bucket, pulp collecting faces something of a paradox. In the unlikely event that droves of previously pulp-deficient homes should suddenly sprout frenzied collectors hellbent on jamming their abodes to the rafters with these decaying prizes, the simple truth is that not enough copies are left to go around. Some titles have likely vanished completely unbeknownst to even the fans. Others are in limited supply, perhaps only in handfuls, and could not support mass interest. In all likelihood, a bumper crop of new collectors would only escalate prices faster, perhaps even out of sight.

So the ugly question arises: what is a reasonable estimate of the lifespan of the pulp-collecting hobby? Much as the last dinosaurs must have glared with angry resignation at the lousy weather, lamenting the fact that it was getting damn cold, certain die-hard pulp enthusiasts are eyeing the calendar and mumbling the unthinkable. How long has the hobby got? To those that genuinely care, it seems terrifying to contemplate a whole chunk of popular culture eroding away. It is by no means impossible that on one not-so-distant day, the whole era will be completely extinct—physically as well as in the common memory. In recent years, a more concentrated effort has gone into reprinting collections of stories as well as complete magazines in both facsimile and near facsimile form, promising that some of the better material will be archived for the future should the demand remain.

The Internet opened previously unknown sources of pulps and united collectors, dealers, researchers and enthusiasts as never before. But will it bring in fresh hands waiting to receive the flickering torch? Or will the faithful continue to chase, cherish and channel every effort into pursuing their inexplicable passion that inspires so many—the unquenchable desire to collect—until that unhappy day when the last original page finally crumbles to nothing.