Not everyone agrees on the definition of “leaf book,” but most collectors seem to recognize one when they see it. In its usual form, a leaf book contains an original leaf from a significant manuscript or printed book, accompanied by an essay written by a knowledgeable, or at least prominent, author. Leaf books have been published by booksellers, collectors, bibliographers, book collecting clubs, and academic institutions, and have been designed and printed by many well-known typographers and private presses.

The main differences of opinion regarding what constitutes a leaf book relate to what accompanying material is necessary. Everyone seems to agree that individual leaves sold separately aren’t leaf books, but there is less unanimity regarding groups of leaves enclosed in boxes or portfolios. If an essay or some other relevant written material accompanies them, most collectors accept them as leaf books. There is less agreement when the leaves are left to speak for themselves or when a single original leaf accompanies a facsimile of the original work.

Although many private collectors tipped in leaves from other books as part of the process of “extra-illustration,” these individually created books are not considered to be leaf books. Standard sources on book collecting and leaf books trace the true beginning of the genre to 1865, with the publication of Francis Fry’s A Description of the Great Bible..., but there are at least two earlier examples. In 1841, the British and Foreign Bible Society published Specimens of Some of the Languages and Dialects, in which the Distribution, Printing, or Translation of the Scriptures, in Whole or in Part, has been Promoted by the British and Foreign Bible Society, either Directly or Indirectly. This volume included 122 mounted leaves taken from previously issued British and Foreign Bible Society publications, along with identifying labels. An enlarged edition published in 1852 included 137 leaves.

Francis Fry’s Description of the Great Bible included fourteen original leaves, which were taken from incomplete or defective sixteenth- and seventeenth-century English Bibles. Fry, a businessman who spent much of his later life collecting and studying Bibles, believed, as he wrote in his introduction, that “no description is equal to an actual leaf.” Reading about a book can be educational and rewarding, but seeing and handling the book—whether the complete object, or a single leaf extracted from it—is a completely different, and potentially much richer, experience. A belief in the power of the original object has been one of the main motivations for the production of leaf books ever since.

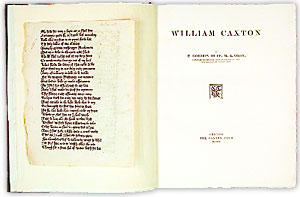

The first few leaf books published after Fry were produced by scholars who used original leaves as specimens to illustrate some or all of the copies of their bibliographical works. G. E. Klemming’s Sveriges Äldre Liturgiska Literatur (Early Swedish liturgical literature) was produced both in folio and octavo editions in 1879, and the folio edition, which was limited to fifty copies, included original leaves from the fifteenth-century books that Klemming described. Konrad Burger included original incunable leaves in Monumenta Germaniae et Italiae Typographica (Monuments of German and Italian typography), which began publication in 1892 and was completed in 1913. Falconer Madan advocated the use of “leaves from real books” in bibliographies in an 1893 address to the Bibliographical Society and followed his own advice with The Early Oxford Press two years later. Not all early leaf books were strictly bibliographical publications. William Harris Arnold’s First Report of a Book-Collector (1897– 1898) was “illustrated with original leaves from damaged books,” and the first 148 copies of E. Gordon Duff’s William Caxton, published in 1905 by the Caxton Club of Chicago, included an original leaf from the first edition of Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales. The club purchased the incomplete Ashburnham copy for the sole purpose of making the leaf book.

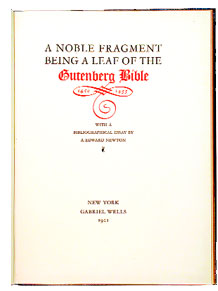

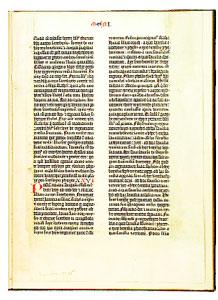

The book collecting boom of the 1920s brought with it significantly increased production of leaf books of all kinds, beginning with what is still the most famous and most expensive leaf book, A Noble Fragment, Being a Leaf of the Gutenberg Bible, 1450–1455. The book featured an essay by A. Edward Newton, who had recently published The Amenities of Book Collecting, an enthusiastic and infectious gathering of bibliophilic essays. Newton’s essay in A Noble Fragment conjured up the magic of ownership of even a small part of the Gutenberg Bible, and placed the purchasers of this book in the company of famous collectors such as James Lenox, George Brinley, Robert Hoe, and Henry Huntington. Gabriel Wells, a New York bookseller, published A Noble Fragment using leaves from an incomplete copy of the Bible that he owned. Wells’s enterprise was profitable and many other antiquarian booksellers have since published leaf books.

Organizations such as the Society of Foliophiles created and marketed several different portfolios of leaves, including Printed Pages from English Literature (1925) and Specimens of Oriental Mss. and Printing (1928). These sets fed the growing market among collectors and libraries for original leaves that shared a common theme or illustrated the development of letterforms or typography. Bibliographer Konrad Haebler was also involved in the publication of several assembled sets of leaves drawn from incunabula, and Otto Ege, a self-proclaimed “biblioclast” (a destroyer of books), sold a large number of single leaves and portfolios. The productions of Ege, Haebler, and the Foliophiles are still sought by collectors and are used for educational purposes by libraries, and other sets of leaves continue to be gathered and sold. One such modern publication is The American Bible, a series of portfolios containing thirty-eight leaves from early American Bibles in the collection of Michael Zinman. In addition to the leaves themselves, the portfolios include explanatory text written by Zinman and an essay by historian of religion Mark Noll. The American Bible was published in 1993 in an edition of 100 sets.

One of the most prolific publishers of individual leaf books has been the Book Club of California, whose first leaf book, Aldus Pius Manutius (1924), combined an essay by Theodore Low De Vinne and a leaf from the 1499 Aldine Hypnerotomachia Poliphili. Since then, the Club has produced more than a dozen leaf books, with the original leaves drawn from books as diverse as the King James Bible of 1611 and the Club’s own first publication, Robert Cowan’s A Bibliography of California and the Pacific West, 1510–1906, which was first issued in 1914.

There is, as yet, no accurate tally of all the leaf books that have been produced, but the total probably exceeds 250, especially if one includes portfolios of leaves, such as those produced by Ege and Haebler, and the many private press bibliographies that include original leaves taken from some of the publications described. There is also a case to be made for counting most issues of Matrix, the annual feast of fine press articles, reviews, tipped in leaves, and samples produced since 1981 by John and Rose Randle at the Whittington Press.

Leaf books have drawn criticism on ethical grounds for more than 100 years. Although they have been the occasion for the publication of significant scholarly essays, this doesn’t necessary balance the harm done by the removal of the leaves from their original contexts. In 1893, Falconer Madan criticized G. E. Klemming for using leaves from “rare and costly books” in his 1879 leaf book, and in the recently published eighth edition of ABC for Book Collectors, by John Carter and Nicolas Barker, Barker states that the breaking up of books “is not to be condoned, even in a good cause.” The ethical issues of leaf books will continue to be debated, but collectors will also continue to compete for them. Although Barker believes that leaf books are out of fashion, their publication rate has shown little sign of slowing down in recent years. Since many collectors would still like to possess an original leaf from a book that they can’t afford in any other form, in the absence of legal protection for copies of important books, entrepreneurial zeal and the marketplace will likely determine whether or not we’re actually nearing the end of the leaf book as a genre.

Beginning in April 2005, an exhibition of leaf books entitled “Disbound and Dispersed: The Leaf Book Considered” will tour the country, opening at the Newberry Library in Chicago, traveling to the San Francisco Public Library, the Houghton Library at Harvard University, and finishing at the Lilly Library at Indiana University. The exhibition, organized by the Caxton Club, will be accompanied by a catalog, which will include an extensive checklist of leaf books, but no leaves.

More information on leaf books can also be found in the “Check List of ‘Leaf Books,’” by John Borden, David Magee, and Duncan Olmsted, published in Quarterly News-Letter of the Book Club of California, Vol. XXVI, Nos. 3 & 4 (Summer & Fall 1961), with an “Addenda” by Olmsted in Vol. XLI, No. 4 (Fall 1976).