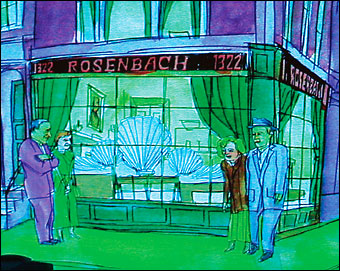

"Fewer babies. More books. Fewer babies. More books.” On the screen at the front of the Adrienne Theater in Philadelphia, a loose sketch of a baby gnawing a book is projected onto the stage. The band breaks into a song while actor Mark Mulcahy, singing the part of Abe Rosenbach, coos a book lovers’ ode to contraception.

The playwright and artist, Ben Katchor, is a graphic novelist whose work has elevated the illustrated book to new heights and new venues—in 2000, he earned a $500,000 MacArthur fellowship, commonly called a “genius grant.” The Rosenbach Company: A Tragicomedy is his third theater piece using projected illustrations. He likes doing theater because in twenty years as an artist, he has only seen one person reading his cartoons, and he likes the instant audience reaction of the performances. “It’s half reading a comic strip, half seeing an opera, and half going to a rock concert,” he said in an interview from his home in New York. “I guess that’s why it’s so entertaining.”

The play, which ran for four performances in September (and will be revived for one night only, on November 9 in Brooklyn), was sponsored by the Rosenbach Museum and Library as part of its fiftieth anniversary. The museum was established in 1954 after the death of the Rosenbach brothers: Abe in 1952 at seventy-six and Philip a year later at eighty-nine. Philip sold antiques and furniture. Abe—Dr. A. S. W. Rosenbach—sold books.

Abe Rosenbach was perhaps the greatest bookseller of the twentieth century, a dealer whose auction purchases made headlines around the world and who shaped and guided most of the great collectors of the first half of the century. As a child he gnawed on books, and as an adult he pioneered the collection of children’s books. There was just one problem: most first editions were either chewed on, scribbled in, or both. He wrote an essay on the subject that prompted Katchor to write the words for “Fewer babies, more books.”

Katchor’s entire script (or perhaps it should be called a libretto) was sung by three actors: Mulcahy as Abe Rosenbach; Ryan Mercy as Abe’s dandified brother Philip; and Katie Geissinger as the Narrator, Isabella, their mother, and other characters. The singers didn’t act, per se, but they certainly evoked the characters as they sang, standing still, reading the lyrics off a podium. Behind them, projected drawings and animation by Katchor established the setting and created the occasional dramatic counterpoint. “I suffer from a terrible disease,” Mulcahy sang, as the word “bibliophile” flashed in red on the screen behind him. “Whose name I won’t mention, if you please.”

The Rosenbach Museum and Library is set up like a dream house for lovers of the ancient and the ostentatious, with its ornate French furniture, a marble and gilt clock that belonged to Napoleon, George IV’s cigar humidor, and a ghostly statue purchased from the New York Metropolitan Museum of Art. Cabinets are full of fine silver and engraved, monogrammed personal effects wrought in gold.

At the top of a curving, spiral staircase is the library, which almost belongs in another house, another world. Its holdings draw scholars who want to study the original manuscripts of Ulysses, Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, and nearly all of the works of Joseph Conrad. On the third-floor shelves are first editions of the first books published in America, London, and Lisbon; the Federalist Papers; Shakespeare’s Second Folio; ten thousand drawings and manuscripts by Maurice Sendak, and countless rare editions. Though Abe Rosenbach bought and sold the Gutenberg Bible many times, the docent explained to me, he never collected a copy because, she said, they were too common. The library, with its well-used reading tables, glows with light reflected from the aged leather bindings that fill the shelves.

In 2001, Bill Adair, the education director of the Rosenbach Museum, called to ask Katchor if he would contribute to the fiftieth anniversary of the museum as part of its artist-in-residence program. After a little cajoling, Adair persuaded him to come down to Philadelphia and check out the museum. “They probably thought I was going to do a book or a drawing or something,” Katchor said. But he told them, “You know, it would be much more spectacular to do a music theater piece.” Other than a dance version of Ulysses a few years before, the museum had never done anything like it. When Philadelphia’s Pew Charitable Trust agreed to fund the project, Katchor and his collaborator Mark Mulcahy were in business.

Katchor read everything he could find about the Rosenbach brothers, relying on published sources like Rosenbach: A Biography by Edwin Wolf 2nd and John Flemming and materials in the museum. He collaborated with Mulcahy to write the original score, and he drew the illustrations that served as backdrops during the performance. All four performances sold out to crowds of enthusiastic bibliophiles.

The play told the story of the Rosenbach brothers with wit and style. Abe’s overbearing brother Philip, his polar opposite in many respects, was also a man of spectacular obsessions. He had a taste for expensive decorative arts, women, and clothes rivaled only by his brother’s passion for books and booze. He was the elder brother and took the lead in the partnership, despite the fact that Abe, with his back office showroom full of books, made most of the company’s money. Philip’s portion of the shop displayed “the latest thing in decorative arts,” as Mercy sang it, with the whining desperation of the tragically hip. “In six months everyone will have one,” he continued, and “at that point the novelty is gone! At that point the novelty is gone!”

The relationship between the two brothers— an interplay of love, mutual dependency, and distaste—was the heart of the show. Both, as Katchor tells it, were lonely, desperate in their success, and unable to tame their demons until it was too late. Adair, reflecting on the show he commissioned, said it had brought him closer to the brothers than years of working in their own home. “I thought it was really unbelievable. It was actually much more beautiful than I thought it could be,” he said. “I think the brothers would have liked it. It told the truth in ways that maybe they wouldn’t have wanted to, but they were both larger-than-life characters.”

Abe Rosenbach made a fortune selling rare books, but in the end the books were more than a living to him. He would sneak books, in a secret pocket inside his suit coat, past his brother and into the house. He read them surreptitiously in bed at night. Many of these books make up the core of the collection at the Rosenbach Museum. When a book touched the notorious dealer, even if it was worth a thousand times what he had paid for it, he gave no heed to profit. “I kept it for myself,” Mulcahy sang with Abe’s self-satisfied glow. “I kept it for myself.”