No other book collecting experience offers quite the thrill of a live auction. It takes nothing away from Internet auctions to note that for sheer emotion, sitting in a room full of other anxious bidders cannot be matched by watching a computer screen at home. No one can sneak in at the last second; you always have another chance to bid. Unlike visiting a bookstore, where a purchase can be contemplated for a few minutes or even a few hours, in a saleroom, decisions must be made in seconds.

The pages that follow document some of the most remarkable of these decisions in 2004: the 296 book, manuscript, and autograph lots that were hammered down for more than $100,000. We also present the complete fb&c 50—the top fifty items from 2004. To make the cut required just over $300,000. Most items on the list have familiar names—Mozart (#14), Lincoln (#16), Newton (#18), Joyce (#21). A few are less well known, like Jacques Vache, an early Surrealist (#34). Declarations of Independence were big in 2004, occupying four of the top fifty spots. Two different editions of the U.S. Declaration finished at #27 and #46. Texas made it all the way to #6, and the Irish Declaration, published in 1916, is #42.

Five authors managed to land more than one item at the top of the list. Shakespeare, of course, is in that very select group. Perhaps more surprising is that a fine copy of the Third Folio (#10) outsold a previously unknown, but incomplete, First Folio (#48). Arthur Conan Doyle checks in with two manuscripts of Sherlock Holmes short stories (#27, 35). French illustrator Pierre-Joseph Redouté made the list twice with a pair of rare hand-colored flower books (#24, 37). The great philosopher Maimonides, the leading Jewish thinker of the Middle Ages, is on at #4 for a fourteenth-century manuscript of Mishneh Torah, his important distillation of Jewish law, and for an incunabulum (#36). However, the writer with more top lots than anyone else is Ernest Hemingway, with three books and a cache of letters in the Fine Books 50 (#31, 33, 44, 49).

In addition to these remarkable stories, we explain how John James Audubon failed to make the grade when he should have and how the Getty Museum placed the top bid of the year yet went home empty handed. Almost anything’s possible before the hammer comes down and the auctioneer says, “Sold!”

It started with what, on the surface, seemed like an obvious question. What do the year’s top sales of rare books at auction tell us about the current state of book collecting? After sifting through nearly 300 sales over $100,000 and narrowing the list down to the top fifty—the Fine Books 50—the answer proved surprisingly simple. Collectors place a premium on one-of-a-kind items and seek objects relevant to their lives.

The Internet might have taken a bite out of the lower-end market, but the high end of the rare book world is doing just fine. As Shannon Kennedy of PBA Galleries in San Francisco notes, “Things that people can’t easily find stick out.” Indeed, the Fine Books 50 shows that the top tier of the top tier is largely dominated by matchless objects like the fantastic Macclesfield Psalter, an English illuminated manuscript that fetched over $3 million (#1 on our list; see page 22). Or the hand-corrected typescript of Alcoholics Anonymous: The Story of How More than One Hundred Men Have Recovered from Alcoholism (1939) that set a California collector back over $1.5 million (#2)—when a first edition of the finished book might cost $20,000.

The substantial number of items that weren’t mass-produced by printing reflects a strong desire among buyers for manuscripts and letters that will set their collections apart. In fact, only just over half (28 lots) of the Fine Books 50 are printed books and ephemera. Unique items make up the remainder: authors’ working manuscripts (10), manuscript books (8), and letters (4).

Why will a collector shell out $528,000 for a six-page musical manuscript by Mozart (#14)? Or $445,480 for an erotic three-page letter from James Joyce to his wife (#21)? Or $331,520 for a collection of short works on astronomy (#40), one inscribed to Christiaan Huygens, after whom the Titan probe is named? There are many possible reasons. As Leah Dilworth, chair of the English department at Long Island University in Brooklyn and author of Acts of Possession: Collecting in America, suggests, we collect because it helps us to establish a framework of meaning in our lives, and the objects we collect, in turn, become imbued with an aura of significance, much like a saint’s relic. We also collect because we’re mortal—and our collections live on after us.

To put it in the words of Nicholas Basbanes, as he writes in A Gentle Madness, “The closer people get to the source, the closer they feel to the wonders of creativity…To see and handle a first edition of Darwin’s Origin of Species or Newton’s Principia mathematica is to touch ideas that changed the way people live.”

If the items at the top of the Fine Books 50 are artifacts that define a collection or library, it’s also true that their provenance will include the buyer as they are passed on through history. The latter is an important point, as illustrated by Glen Miranker, a major Sherlock Holmes collector. When part of a previously lost archive of materials from Sir Arthur Conan Doyle was to be auctioned by Christie’s, the world’s foremost Sherlockian, Richard Lancelyn Green, feared that putting the archive in the hands of a private collector or collectors would limit scholarly access. Green’s subsequent mysterious death was the subject of a long profile in The New Yorker, to which Miranker, a friend of Green’s and one of two private collectors to purchase the lion’s share of the Holmes material in the archive, responded with a letter to the editor. “The sale posed little threat to scholarly work or accessibility,” he wrote. “We take our custodial responsibilities as collectors very seriously.”

Steven Gelber, professor of history at Santa Clara University in California and author of Hobbies: Leisure and the Culture of Work in America, points to this as a major facet of collecting. “As a historian,” he says, “I think collectors are wonderful people. They spend their own money to get material that is on the public market, and they often rescue it from being ignored or destroyed or discarded, which is the fate of most objects in a throw-away industrial society.”

Even so, only items with generally broad appeal can bring several collectors together both willing and, more important, able to let loose a sum in the mid-six figures for a book. For this reason, the top of the market is crowded with books and manuscripts that get many people excited. These collectors, for the most part, are not forging new paths—in the U.S. and Western Europe, men (more so than women, probably for both cultural and economic reasons) “have historically collected in a pattern that tends to replicate market mechanisms,” Gelber says. “That is, they collect things that have market value, and they are concerned about the market value of the things they collect.”

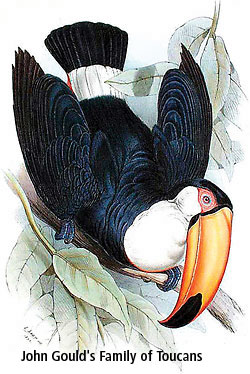

It helps if the books are gorgeous. Bookseller Ralph Sipper told The Financial Times, “If you are going to buy books, you have to be attracted to them in a very visceral way.” Consider the large number of natural history books with hand-colored plates. Such books have been popular for centuries and became something of a cottage industry in the nineteenth century. Thirty-five plate books sold for more than $100,000 last year, with several great artists represented in the Fine Books 50: John Gould (#46; see page 25), Maria Sibylla Merian (#46), Pierre-Joseph Redouté (#24, 37). John James Audubon’s The Birds of Americashould have made the list but didn’t (see page 29).

The overall auction results also show a much more specific appreciation of timeliness. A printed broadside of the Texas Declaration of Independence brought $764,000 (#6), perhaps influenced by a hotly contested U.S. presidential election with a fiercely Texan incumbent. As PBA Galleries’s Shannon Kennedy says, “All things Texas are hot.” And Copernicus (#3) will always bring a high price, but certainly the publication of Owen Gingerich’s The Book Nobody Read: Chasing the Revolutions of Nicolaus Copernicus raised awareness and added to the back story.

In general, twentieth-century works are surprisingly attractive to collectors right now. This certainly explains in part why a manuscript copy of a work by the Venerable Bede from the twelfth century fetched only $123,000 at auction (#224 for the year), while Alcoholics Anonymous gets over $1.5 million. “The culture is telling us a one-thousand-year-old document isn’t as relevant as a seventy-year-old document,” suggests Leah Dilworth, “and thus not as economically valuable.”

While the oldest item on our list—a marvelous Buddhist scroll (#43)—dates from as early as the sixth century, almost as many items are from the twentieth century (17) as the sixth through seventeenth centuries, combined (18). In part, this is due to two sales of the extraordinary Maurice Neville collection of modern literature and the strength of modern artists’ books (see page 31). As Nick Basbanes put it recently, “There’s not some grand manipulator up there… Material has to be available. People have to be willing to sell.”

Jeremy Norman, a dealer in science books, isn’t surprised by the strength of comparatively recent material. “The twentieth century is more relevant to our time,” he says. “I find working with newer things very exciting. It’s fun to find and collect things that haven’t been collected before.” The interest in new material in science is demonstrated by the $104,000 (#278 for the year) paid for James Watson and Francis Crick’s second paper on DNA, Genetical Implications of the Structure of Deoxyribonucleic Acid, published in 1953. (James Watson shares with Martiniquais poet Aime Cesaire the distinction of being one of two living authors with items on our extended list.) The growth in biotechnology and the wealth of company founders is creating demand for key works in biology like Mendel’s paper on heredity, just outside the Fine Books 50 at #61 ($270,000) and Linnaeus’s twelve- page paper classifying species ($517,000, #15).

Another confluence of interest and availability places six examples of Judaica on the Fine Books 50. Between the Sotheby’s auction of the collection of manuscripts manuscripts deaccessioned from the Montefiore Endowment in Britain and the sale of the Wineman incunabula by Kestenbaum & Co., it was a banner year for Hebrew books. The thirty-nine lots that made over $100,000 brought $8.9 million into the auction houses. Daniel Kestenbaum notes a strong market in New York for Judaica but wonders at the lack of interest on the part of collectors and dealers who aren’t Jewish. Referring to the recent sale of a remarkable group of rare books in Hebrew from the earliest days of printing, he said, collectors of incunabula and printing history “were not present in this auction, which I find astounding. The first book printed in Portugal was in Hebrew. The first book printed in the Ottoman Empire was in Hebrew. Hebrew books are overlooked. Every item in this sale went to either Hebrew libraries or collectors of Judaica.” Nevertheless, the sale grossed nearly $4 million and placed an important incunabulum on our list (#36).

What will the highspots of 2005 be? It’s too early to tell, and we don’t dare predict what collectors might do in the new year. As Steven Gelber says, “We tend to think that human beings—homo economicus, economic man—do things rationally and objectively. But, of course, that’s not true at all.”