Britain loves nothing as much as an unfair fight. When Goliath threatens, we’re right behind David. In this case, the underdog was the Fitzwilliam, the art museum of the University of Cambridge; Goliath was California’s Getty Museum. The prize at stake was a tiny, four-inch by seven-inch, fourteenth-century devotional book, mislaid for more than a century between two undistinguished divinity texts in the Earl of Macclesfield’s library, in the moated Shirburn Castle in Oxfordshire.

A rancorous family dispute has led to the eviction of the present Earl, who gets to keep the contents but not the castle. So most of his magnificent library, described by Sotheby’s as “the last great country-house library in England,” is going on the block in a series of sales. The Psalter, cataloged as “the most important discovery of any English manuscript in living memory,” easily outstripped its estimate, falling to the Getty on June 22, 2004, for £1.7 million ($3.1 million).

End of story? No, just the beginning, as civil servants, experts, charitable funds, and the British press limbered up for a battle royal to “save” the Psalter and prevent its export under British antiquities law. “It’s a unique piece of English heritage,” explained David Barrie, Director of the National Art Collections Fund. “It’s an object of outstanding artistry, produced at a time when this country’s illuminators were famous throughout Europe. Very few works of such quality remain from that period in our history, and it was essential that we launch a public appeal to save this remarkable object.”

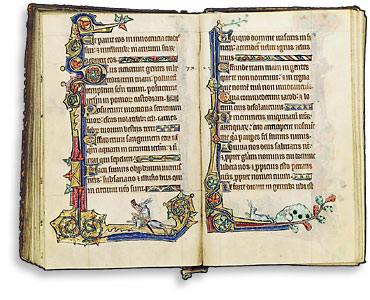

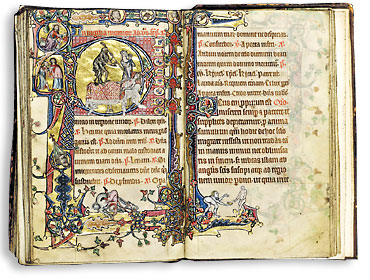

Henry VIII’s Reformation and the wholesale destruction of Catholic artifacts left the Psalter as a rare window into the medieval world, where the secular and devotional, the sacred and profane, jostle for attention. In the Psalter, dogs dressed as bishops, urinating men, bare bottoms, rabbits, pigs in turbans, an astonishingly naturalistic skate all embellish a text comprising prayers and psalms. “As a Psalter, it was the typical book for private devotion,” explained Dr. Stella Panayotova, Keeper of Manuscripts and Printed Books at the Fitzwilliam. “But its size and incredibly dense illumination are exceptional—I would say, unique. The artist’s uninhibited imagination breathes life into his technical perfection. It’s the perfect blend of devotion and humor, both in extraordinary measures. It’s like an imprint of its owner with biblical images, courtly scenes, and absurd marginalia. It’s the whole medieval world gathered in a microscopic scale.”

Does it really matter, given digital scanning and Internet access, where the Psalter actually resides? It was, after all, until its discovery by an astonished Sotheby’s director Paul Quarrie, on a high, dusty shelf, not available to anyone. “In terms of digital access, it doesn’t matter where the Psalter is,” argues Panayotova. “In every other aspect it does, as the Getty knows, since they would like to have the original, not just a digital facsimile.” In order to keep the Psalter in the country, the Fitzwilliam had to match the Getty’s bid and pay Sotheby’s buyer’s commission. The museum announced on January 25 that it had raised the necessary sum.

The Getty Museum declined to comment on the matter, and who can blame them? They agreed, generously, if reluctantly, to allow the BBC to film the Psalter, and that footage formed a key element in the fund-raising efforts that ultimately kept the Psalter in East Anglia, where it was originally produced. So, rather than displaying the artifact in its galleries in sunny California, it is the Getty that will have to make do with digital scans and the promised facsimile editions.