At age 13, Richard Minsky bought his first printing press—his first real printing press, he is quick to add—which replaced the rubber stamps he printed with before. Since that day in 1960, he has pursued nearly every avenue of the book arts—letterpress printing, bookbinding, leather tanning, papermaking, and illustration. He has also created one-of-a-kind objects based on books that are closer to conceptual art or sculpture than the output of traditional fine presses. And along the way, he founded New York’s Center for Book Arts, the first such organization in the United States and still the most influential.

In the early 1970s, Minsky was working as a bookbinder, repairing books and crafting fine bindings for clients. His fledgling career took a dramatic turn when an aging book on mummies came in for repair and instead of simply fixing it, he proposed rebinding it in strips of linen like those used on its subject. The result helped move bookbinding from a craft into an art. Two years later, Minsky affixed a salted pheasant skin to a copy of J. J. Studer’s 1888 book The Birds of North America and placed it in an exhibit of finely tooled leather bindings. The controversial book crystallized a central idea behind Minsky’s subsequent work: using materials as a metaphor for the content of the book. The dead bird recalls the techniques of nineteenth century naturalists who routinely shot animals so they could draw them more accurately. When the exhibit curator, Dale Roylance from the Yale University library, asked how this kind of book should be shelved, Minsky replied, “You don’t stick it on a shelf next to other books. It’s a work of art, like a sculpture, and you exhibit it like that.”

Although Minsky continued to make elegant leather bindings, he also used a rat skin he personally tanned for a book by punk icon Patti Smith and draped barbed wire around The Crisis of Democracy, a book that suggested that democracies could not survive unfettered personal freedoms. These unusual materials invoke strong reactions because of something Minsky calls “museum finish”—the extraordinary sensation a great work of art induces when it is seen for the first time.

When he went to museums, he explained, “the space around some pieces seemed to vibrate, and I wanted to know why. After studying the philosophy of art, I realized that when looking at a work with ‘museum finish,’ it’s seen as a material object—as paint, a piece of stone, whatever it is. It also has a visual image, and that image evokes a metaphor, which invokes an internal experience of what it’s about. During that moment of internal experience your attention is diverted from the artwork. If the material is used well, it reminds you that it’s there, and the image then reasserts itself. The mind acts like the shutter of a movie projector, cycling perception between the material, image, and metaphor many times each second, creating the illusion of flickering space.”

Minsky is currently interested in social and political metaphors. He seeks books with important implications for contemporary society and binds them to call attention to the core message of the text. He considers books an ideal medium to express complex ideas. “There’s the initial visual impact,” he explained, “and the opportunity to explore the issue in more depth right there in your hand.” When the work is on display in a case, it “creates a tension, the desire to touch and feel and read, but the book is on the other side of the glass,” Minsky said. “I try to use that in the art.”

That tension is perhaps most evident in his series on the Bill of Rights. Beginning in 1993, he envisioned ten individual pieces, each devoted to one of the amendments. After creating three unique pieces, the project expanded into an edition limited to twenty-five sets of ten books. When the work is displayed in galleries or museums, the glass between the viewer and the artwork heightens Minsky’s message that constitutional rights are moving out of reach. Minsky has completed seven sets and expects it will take another decade to finish the rest. He will not sell the books, priced at $18,000 for the ten-book collection, separately. “The government is trying to take [rights] away one by one,” he told the New York Times. “You have to have them all.”

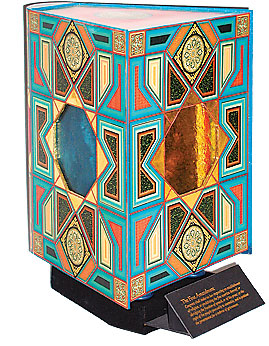

The books in the series vary widely in format. A book-shaped reliquary, decorated with patterns inspired by Islamic designs, signifies the first amendment to the Constitution. In each vessel are the ashes of a copy of Salman Rushdie’s The Satanic Verses. More than any other book, Minsky said, Rushdie’s novel and the resulting fatwa symbolize “how, with one book, you can lose four freedoms: speech, the press, religion, and assembly.” He likened his burning of the book to the “many saints sacrificed for their beliefs. I’m burning them as a warning,” he said.

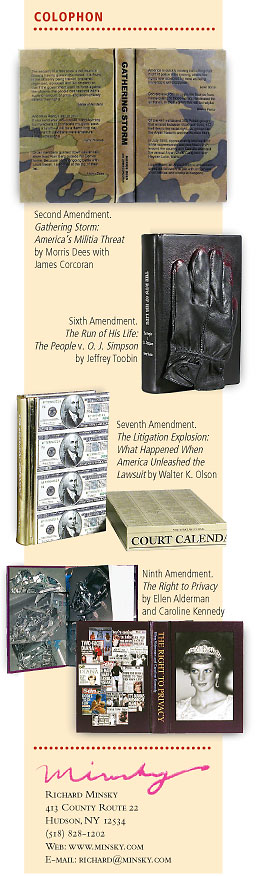

A book, bound in camouflage, about right-wing militias symbolizes the Second Amendment, the right to bear arms. Minsky’s third piece, representing the prohibition on quartering troops in private homes, is an attaché case containing a specially bound copy of Seven Days in May, about a general who seeks to quarter himself in the White House. Enclosed with the book is a DVD of the movie. For the Seventh Amendment, the right to a trial by jury for civil cases over twenty dollars, Minsky bound a book on frivolous lawsuits using phony twenty-dollar bills with Jackson’s face replaced by the father of the Bill of Rights, James Madison. The slipcase is covered with announcements of lawsuits. Other books in the series have been embedded with electronic equipment, shot with a pistol, attached to a jail-like case by a chain, and bound in a classic law book style. Such is Minsky’s devotion to the project that when he discovered that a bo ok he wanted to use was out of print, he obtained permission to publish twenty-five copies just for this project.

The Bill of Rights, as a group, confirms Minsky’s mastery of a wide range of materials and techniques. While art critic Rose Slivka called Minsky “the foremost American exponent of modern bookbinding as the art of amplification on the book,” and his works are in numerous libraries and museums, he says, “I don’t believe in talent.” His knowledge of so many of the book arts is the result of persistence. “If you have an affinity for something and keep doing it, you get better at it. If you live long enough, you can do anything.”