FINE MAPS

A Million-Dollar Map

Seven Figures for Seven Letters: AMERICA

Although most people collect maps for their own sake,

we may dream that one day something in our collection that was purchased

for a pittance will turn out to be worth millions. That’s what happened

to a German book collector recently. Drinking coffee and reading his newspaper

one morning, he saw an article about a rare map and realized that he had

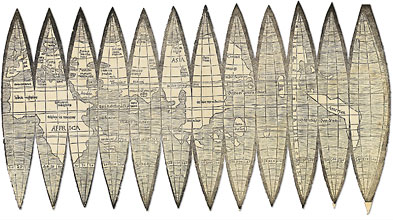

one that looked awfully similar. His small woodcut map of the world was

arranged in jagged sections— called globe gores— designed to

be cut out and glued onto a sphere to create a four-and-a-half-inch-diameter

globe. The German collector’s example had already been cut out like

that.

Photo Courtesy: Christie's

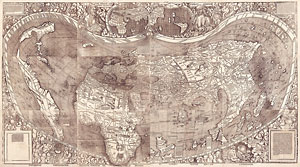

This world map by Martin Waldseemüller, the

first to use the word “America,” sold for more than $1 million

on June 8.

His globe gores turned out to be part of a set

of materials first published in 1507 by Martin Waldseemüller—a

German cleric, scholar, cosmographer, and cartographer— and several

assistants. In addition to the globe gores, they produced a large wall map

and a booklet describing the maps. Waldseemüller’s world map

was one of the first to include geographical features from the reports of

the explorers who sailed west from Europe after Columbus. He had examined

the accounts of Amerigo Vespucci’s voyages to South America between

1497 and 1504, and he used that information to draw the east coast

of the continent. He had no accounts of the geography beyond the Caribbean,

so the coasts of most of North and South America were pure guesswork. Waldseemüller

honored Vespucci’s discoveries by labeling the new continent America,

a name that stuck. The name was actually suggested by Waldeseemüller’s

assistant, Matthias Ringmann, who wrote the introduction to the map, called

the Cosmographiae Introductio: “There is a fourth quarter

of the world which Amerigo Vespucci has discovered and which for this reason

we can call ‘America’ or the land of Americo.” This

was the first use of the word “America” on any printed

document, and Waldseemüller’s use of it was l.ikewise its first

on any map.

There were, until our coffee-drinking collector

realized what he had, only three sets of the globe gores known to exist.

A number of copies of Cosmographiae survived, but the first gores

were not discovered until 1871. That map now resides in the James Ford Bell

Library at the University of Minnesota. The two other copies are in Germany,

one at the Bavarian State Library, and the other in a public library in

the small town of Offenbach, having been found bound into an unrelated library

book in 1992. The German collector’s map was put up for auction at

Christie’s in London and sold on June 8 for slightly more than a million

dollars (£545,600 or $1,002,267, including the auction premium), a

price just below the low estimate. The buyer was Charles Frodsham and Co.

Ltd., a London antique-clock dealer. The three other known copies are on

full sheets of paper, so the fact that this set was cut out undoubtedly

kept bidders from reaching deeper into their pockets.

The survival of maps in general seems to

be inversely correlated with size; the larger the map, the rarer it tends

to be. A good example of this is Waldseemüller’s wall map, which

measures eight feet by four feet. The Library of Congress purchased the

only known copy four years ago from a German collector. It survived because

its twelve separate sheets were bound into a portfolio that had been put

together by German globe maker Johannes Schöner. At some point, the

portfolio was acquired by the library of the Castle of Wolfegg, at Wurttenburg,

and was discovered in 1901 by a Jesuit historian, Josef Fischer. Luckily,

by this time the map was old enough to be recognized as valuable. Following

years of negotiation and diplomacy, the Library of Congress acquired the

map and an export license at a cost of $10 million.

The Library of Congress paid $10 million for

this wall map by Waldseemüller.

Photo Courtesy: Library of congress

After such a high-profile purchase, made with $5

million appropriated by Congress and a matching amount raised from private

donors, some have questioned whether the map is actually a first printing

from 1507. The watermarks on the paper match another map more definitively

dated eight years later (indeed, Christie’s gave a 1515 date for the

Library of Congress map in its press materials). While there is no historical

evidence of a second printing of the wall map, it is not inconceivable that

the wood-block plates could have been reused at a later date. The question

is somewhat academic since the Library of Congress’s map is one of

a kind, but for collectors keen to own what has been called the “birth

certificate of America,” a later date for the wall map would mean

the globe gores are the sole surviving first appearance of the word “America” on

a map.

When I asked Dr. John Hébert, chief of the

Geography and Map Division at the Library of Congress, for his view, he

dismissed the later date as speculation and vigorously defended the 1507

date for the library’s wall map. He pointed out that the watermarks

are only on the descriptive text pasted onto the corners of the maps and

that the dating of the watermarks themselves is far from certain. This is

true. The dating of the watermarks is derived from the fact that they are

the same as those on another Waldseemüller world map, called the Carta

Marina, which has been more positively dated to 1515. The two maps could

have the same watermark simply because the printer had a lot of paper with

this watermark and used the same paper for both maps.

The watermark evidence from the globe gores adds

to the confusion. The four copies are printed on three different papers.

The watermarks on the globe gores sold at Christie’s and on the University

of Minnesota copy have been dated by some to 1526, not 1507, but that later

date is not certain either. All of which illustrates the difficulty dating

old maps, and the uncertainty likely contributed to a lower-than-estimated

auction result for the globe gores. The Library of Congress declined to

bid because of it, and others may have as well.

But what is the special appeal of the Waldseemüller

maps, other than simply being the first to name America? The answer lies

in a few other “firsts” claimed by the maps. They are the first

printed maps to depict a North American continent in the western Atlantic

and the first to show the New World as an entirely separate continent. They

are also the first maps to depict all of South America and the Pacific Ocean

beyond, or at least a separate ocean between Asia and America, an ocean

that was not physically discovered until 1513 by Vasco Núñez

de Balboa, when he crossed the Isthmus of Panama. The existence of the Americas

dispelled Christopher Columbus’s hope that there was an easy ocean

route to the riches of the East and the Spice Islands by sailing west from

Europe. As Ferdinand Magellan was to discover in 1519, getting around the

Americas required a long and arduous voyage. Emerging from the strait he

found at the tip of South America on an unusually peaceful day, he named

the ocean he found what it was not: the Pacific.

Map makers of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries

usually had to work with incomplete information and often resorted to what

passed as logic to depict what they thought ought to be, and Waldseemüller’s

group, following Vespucci, thought that there ought to be another continent

before the coast of Asia was reached. It was probably little more than an

intuitive leap but they had the fortune to have guessed correctly. All other

maps up to that point either had shown America as an eastern extension of

Asia or had conveniently run the western edges off the maps, thus evading

the question.

Waldseemüller’s maps, with as many as

1,000 copies distributed, influenced many later cartographers, and had far-reaching

geographical implications. His map was the embodiment of such a revolutionary

new notion of the world that, on that basis alone, it certainly qualifies

as a landmark map. The fact that so few survive, whatever their actual dates,

virtually guaranteed that one offered for sale would produce a jaw-dropping

price.