Marbled paper

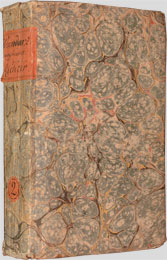

One of the most common methods of decorating the endpapers

of hand-bound books is marbling. Although collectors and others who are

used to handling and viewing books of the past often take little notice,

to those who haven’t encountered marbled paper before, its splendid

variety of patterns and colors can be an eye-opening experience.

Far from being a recent decorative innovation,

the marbling of paper dates back to at least 1118 a.d. and a Japanese publication

whose title translates as Poetical Works of the Thirty-six Men.

The paper was produced by a method known in Japan as suminigashi,

or “a pattern formed by floating ink,” which aptly and concisely

describes the nature of the process. Marbled paper is created by floating

colors on the surface of water, working the colors into patterns, and then

transferring the pigments onto a sheet of paper. Books covered with these

geometric and random patterns of color can be quite striking.

Marbled paper was in use in the Near East in the

succeeding centuries after its documented appearance in Japan, though it’s

not known whether it developed independently or if it migrated westward

from Japan or China. European travelers must have seen marbled paper when

they visited Persia and Turkey in the sixteenth century, and by the early

seventeenth-century, similar paper was being produced in Germany. The craft

of paper marbling spread quickly to France, and eventually to the rest of

Europe. John Evelyn demonstrated marbling to the Royal Society in 1662.

Before marbling became an established trade in England in the late eighteenth

century, marbled sheets imported from the Continent proved very popular

among bookbinders, who used them frequently for endpapers and the coverings

of bindings. Marbling arrived in the United States in the early nineteenth

century.

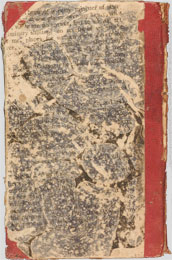

In addition to blank paper, artisans also marbled

surplus or waste sheets, and it is this practice of recycling that created

some of the marbled sheets most prized by Americana collectors. Sometime

after 1800, a still-unidentified printer in New England undertook an edition

of John Cleland’s notorious Memoirs of a Woman of Pleasure (known

colloquially as Fanny Hill, after its main character). The title-page

falsely identified it as having been produced in “London: Printed

for G. Felton, in the Strand, 1787.” For reasons that are still the

subject of speculation, the printer abandoned the edition, apparently after

completing the first part of the book. The printed sheets were marbled (“overmarbled”

is the technical term) and used to cover the plain board

bindings of books of all kinds. Over the years, the marbling has worn away,

revealing—on a variety of much more innocent books, ranging from textbooks

to religious works—portions of the beginning of the story of Fanny

Hill. A number of these books survive, and they appear on the market from

time to time, where they are acquired far less for their texts than for

what is revealed beneath the marbling.

While marbled paper was widely used on books well

into the nineteenth century, its popularity slowed after the mechanization

of new-book binding. Marbling never died out completely, however, and it

remains popular today both for custom bookbinding and as a craft practiced

by people of all ages.

Paper marbling seems magical, and yet it is improbably

simple. The basics haven’t changed very much over the past several

hundred years. It still involves depositing bits of color on the surface

of water (to which a thickening agent has been added) and arranging those

colors, through the use of combs or other implements, into patterns that

are then transferred to a sheet of paper. It is fairly simple to follow

a manual and produce a sheet of marbled paper, just as one can also follow

instructions and produce a sound by drawing a bow across the strings of

a violin. In each case, one will get results, but the results may not be

pleasing. With marbling, it takes practice to learn the proper amount of

thickening agent to add to the water so that the colors will float and some

experimentation to create pleasing patterns. Placing and removing the paper

to be marbled from the surface of the water also requires delicacy. With

diligence and experience, the results do improve, and paper marbling can

become an addictive hobby.

Many marbled papers used for endpapers and bookbinding

have similar designs. Applying the colors to the water’s surface in

a set manner and manipulating them with specific combs, as described in

marbling manuals, create standard patterns. While the sheets will exhibit

some variation, an experienced practitioner can create very similar and

consistent designs.

Not all of the decorated paper found in books is “marbled.” Some

designs are produced using woodblocks or engraved plates, while others have

patterns created by a process involving colored paste. These “paste

papers,” as they are known, are also quite common on book bindings.

Further Reading

The

standard history of the field, which was of great help in the writing of

this article, is Richard Wolfe’s Marbled Paper: Its History,

Techniques, and Patterns (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania

Press, 1990). Wolfe covers both Eastern and Western marbling, with particular

emphasis on marbling in Britain and America. His detailed notes are essential

for anyone doing research in the field. A more general account of several

types of decorated paper is Rosamond B. Loring’s Decorated Book

Papers: Being an Account of their Designs and Fashions (Cambridge:

Harvard College Library, 1942). Later editions, edited by Philip Hofer,

contain additional essays about Loring’s life and work. They do not,

however, include original samples of marbled and decorated papers included

in the 250-copy first edition. No list, however brief, of reading about

marbled paper should exclude mention of some of the many works on the subject

published by the Bird & Bull Press of Henry Morris: The Mysterious

Marbler (1976); Karli Frigge’s Life in Marbling (2004);

and The World’s Worst Marbled Papers (1978), complete with

paper samples.

The

standard history of the field, which was of great help in the writing of

this article, is Richard Wolfe’s Marbled Paper: Its History,

Techniques, and Patterns (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania

Press, 1990). Wolfe covers both Eastern and Western marbling, with particular

emphasis on marbling in Britain and America. His detailed notes are essential

for anyone doing research in the field. A more general account of several

types of decorated paper is Rosamond B. Loring’s Decorated Book

Papers: Being an Account of their Designs and Fashions (Cambridge:

Harvard College Library, 1942). Later editions, edited by Philip Hofer,

contain additional essays about Loring’s life and work. They do not,

however, include original samples of marbled and decorated papers included

in the 250-copy first edition. No list, however brief, of reading about

marbled paper should exclude mention of some of the many works on the subject

published by the Bird & Bull Press of Henry Morris: The Mysterious

Marbler (1976); Karli Frigge’s Life in Marbling (2004);

and The World’s Worst Marbled Papers (1978), complete with

paper samples.