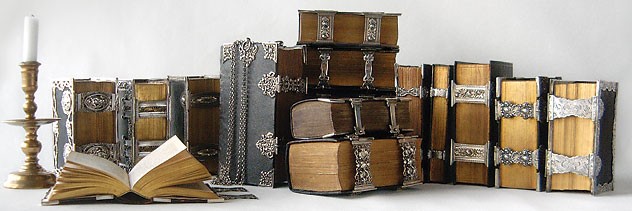

Sabbath Silver

Holy Books from the Collection of Bernard van Noordwijk

In an era when leather bindings on books are considered a

luxury, it is easy to forget that for most of the book’s 2,000-year history, almost all

volumes were bound in calf skin or sheepskin. For centuries, book owners

desiring something more lavish than utilitarian

leather commissioned elaborate designs to be worked into the cover, or decorations of jewels or ivory. The most ornate treatments were

reserved for Bibles and other holy books owned

by the church or nobles. In the seventeenth century, ornate silver

decorations became affordable to and popular among the burgeoning middle

class of successful merchants and lesser nobles. These bindings indicated the importance of the books, the

wealth of their owners, or both at the same

time. For nearly two centuries, books adorned with silver were popular in

Western Europe.

Bernard van Noordwijk, a retired Dutch management

consultant, has assembled an extensive

collection of books with silver adornments. He is interested in small volumes of religious texts such as

prayer books, missals, and hymnbooks, the sort of book that someone,

usually a woman, would have carried to church. The books themselves—standard religious texts in most

cases—are often not particularly valuable. European printers

manufactured them in vast quantities, and they can be found in any good

antiquarian shop. The silverwork on the bindings, however, makes them

special as objects and as a record of European church fashions from the

seventeenth through the nineteenth centuries. They were bound and adorned

centuries after books no longer needed to be chained to shelves for

safekeeping, yet some of them incorporate chains into their design. The

silver chains may have even allowed their owners to carry them like

handbags. The books

were anachronisms and impractical in one key respect: The metalwork prevented them

from being stored with other books. Pulling them on and off the shelf would

scratch and tear the covers of the adjacent volumes. Van Noordwijk believes

the books were typically displayed on a mantelpiece when not in use.

While books adorned with silver were probably fairly

common at one time, most of them have been disassembled because the silver

is worth more than the book. In fact, that’s how van Noordwijk

started collecting these books. Thirty-five years ago, he noticed that one of his

wife’s silver bracelets appeared to be fashioned from a book clasp.

Early binders mounted brass clasps or affixed leather ties to the edges of

books to hold them closed when they weren’t in use. Before bookcases

came into widespread use, books were often

stored flat on a shelf or locked in a trunk. With time and use, the pages

tended to warp slightly, preventing the covers from closing tightly.

Eventually, this would damage the book and make it susceptible to dust and

insect pests. The solution was to clamp or tie the book closed when it

wasn’t in use. Before he realized that his wife’s bracelet had

once been part of a book, van Noordwijk had

never paid much attention to books with clasps fashioned from silver.

As often happens with collectors, once he knew what he

was looking for, van Noordwijk soon spotted other books with ornamental

silverwork still attached. The first example he found seemed too expensive, and he

didn’t buy it. He continued to think about it, however, and

eventually returned prepared to pay the asking price. The book was gone,

sold to have its clasps made into knife rests, according to the shopkeeper.

Thus began three decades of collecting to save silver-adorned bindings from

being converted into jewelry or dining room accessories. The books, valued

mostly for their silver content, typically cost a few hundred to a few

thousand dollars. Van Noordwijk’s efforts to preserve these

endangered books will culminate in a February through June exhibition of

his books at the Bijbels Museum (Bible Museum) in Amsterdam, where he is a

guest curator. The

examples that follow will be depicted, with many other books from his

collection, in the illustrated exhibition catalog, which will provide the

most extensive documentation of silver-adorned bindings to date.

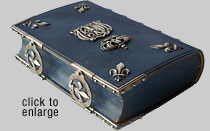

appears at the corners and on the clasps and enhances the religious symbolism of the binding materials.

appears at the corners and on the clasps and enhances the religious symbolism of the binding materials.