The British Library

Giving the Past a New Future

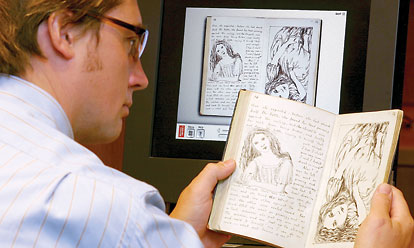

A curator compares the original manuscript of Alice’s

Adventures Undergroud , given by Lewis Carroll to Alice Liddell

in 1864, with the British Library’s

“Turning the Pages” digital facsimile.

You could be forgiven for assuming the British Library

is a truly ancient institution, populated by dusty academics and bearded

revolu tionaries poring over Victorian tracts For an organization so dedicated

to knowledge, the Library has been con stantly dogged by profound ignorance

Steve Hare demolishes a few myths.

Every civilized country boasts a national library.

It is an essential part of any definition of “civilization.” What

often starts with the gifts of generous patrons and avid collectors is usually

formalized at some point by the notion of legal deposit: a law dictating

that a copy of every item published in the country is to be given to the

national library. A collection of treasures thus becomes a point of access

for the country’s collective genius and a major research facility.

The Library of Congress, in Washington, D.C., dates back two centuries and

its Thomas Jefferson Building to 1897. If that library is the world’s

biggest, the British Library is not far behind, managing 400 miles of shelving

against the Library of Congress’s 530. But it might just pip them

for the sheer size of its collection, with an estimated 150 million items

against the American national library’s 130 million. That’s

no surprise, surely, since the British Library must have been around forever?

In fact, far from being an ancient institution,

the British Library only came into being in 1973 and didn’t have its

own building until 1997. Prior to that, it was primarily a department of

the British Museum, from that institution’s foundation in 1753. Today,

the Round Reading Room, where Karl Marx researched Das Kapital, is

primarily a tourist magnet within the Museum’s Great Court, half a

mile south of the new Library, and now light years away in approach, attitude,

and facilities. The old Museum Library—the first public library in

Britain—struggled desperately in its later years to house and conserve

its rapidly growing stock. Much of the collection was dotted around London,

often in damp basements, and ordering an obscure title might entail a wait

of weeks for the hapless researcher. The solution to this increasingly urgent

problem was to establish the Library as a separate entity with its own dedicated

building.

The flagship home for the national collection,

the new British Library complex on Euston Road in the heart of London, broke

ground in 1982 and finally opened in 1997. It’s a minor miracle of

engineering, though most visitors will never be aware of this. The book

stacks and mechanical handling systems are all far below ground and out

of sight. The exterior is a magnificent response to its location and neighbors,

a stark 1960s office block on one side and the magnificent neo-Gothic of

St. Pancras Station and its accompanying hotel on the other. Behind the

library, amongst a forest of cranes, the new Channel Tunnel terminal is

emerging (confusingly enough some seventy miles from the actual tunnel at

Dover).

This whole site was once a huge Victorian goods

yard where the coal that caused London’s smog was delivered to the

capital by steam train. Long derelict, the site was finally picked for the

library, once officials ditched an earlier proposal to flatten several acres

of Georgian architecture on Bloomsbury Square, to the eternal gratitude

of local residents, academics, and conservationists.

Planning for this, the largest public-sector development

in twentieth-century Britain, started in the 1950s and was never rushed.

It became not simply a commission, but virtually an entire career for architect

Colin St. John Wilson and a constant source of frustration and compromise.

With funding released in an unsteady and reluctant trickle, his ideas and

ideals took a battering from succeeding governments—particularly when

the property boom of the 1980s prompted Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher

to argue that a potentially lucrative chunk of real estate was being wasted

on mere books. The site was carved up and future construction phases summarily

cancelled, ending forever the library’s hope of housing the entire

collection on a single site. The delays and endless changes drove the project

cost from £36 million (about $90 million in the late 1960s) to £500

million ($820 million) by its completion three decades later.