Book Reviews

Melville

His World and Work

By Andrew Delbanco

New York: Knopf, 2005

415 pages. $30.00

ISBN 0375403140

Though Melville had been born and died in the

nineteenth century, Moby-Dick was the work of a twentieth-century

imagination

Literary biography is a mongrel genre, mixing

historical biography with literary criticism. Mediocre literary biographies

merely recycle fact and gossip about the author but offer no insight

about how their works were written and received, and why they continue

to endure. Andrew Delbanco’s Melville: His World and Work belongs

among the superlative breed of biography. It’s an outstanding

reappraisal of Melville, a reminder of his importance in American literature

and his relevance in our time.

When Melville died in New York City in 1891,

many of his contemporaries were surprised to see his obituary—they

thought he had died long before. After the Civil War and the commercial

and critical failure of Moby-Dick, Melville stopped writing

for publication. Of his seventy-two years, Delbanco notes, only twelve

were devoted to writing prose that was published in his lifetime.

Melville was born in 1819 in a newborn nation.

Giants such as Adams and Jefferson were still alive, the nation’s

economy was mainly agrarian, and slavery flourished. “During

Melville’s childhood,” Delbanco writes, “the rhythm

of American life was closer to medieval than to modern, but by the

time he grew old, he was living in a world that was recognizably our

own.” American literature, as embodied by Hawthorne and Emerson,

was also coming into its own during Melville’s adolescence.

Melville spent only three years on the high

seas—one year sailing to London and back, and another two in

the South Pacific and Hawaii. These voyages provided the content of

his earliest and most successful books, Typee and Omoo.

He planned to make a comfortable living as a professional writer, married,

and moved between Arrowhead, his family estate in western Massachusetts,

and the bursting metropolis of New York City.

Delbanco believes New York City played a larger

role in Melville’s life than many critics have acknowledged. “I

have swam through libraries,” Melville wrote, absorbing the works

of great European authors in the city’s private and society libraries.

His middle-period novels—Mardi, White-Jacket and Redburn—reflected

these influences and showed maturity, tackling social, political, and

philosophical issues. Most of his characters were drawn from urban

landscapes, not from his maritime experiences. Melville once observed, “Where

does any novelist pick up any character? For the most part, in town….

Every great town is a kind of man-show, where the novelist goes for

his stock.”

Everything was a prelude to the book he began

writing in 1850, “a strange sort of book” about a whaling

voyage. Delbanco makes a convincing argument that Moby-Dick was

the first modern American novel: “a young man’s coming-of-age

story, an encyclopedic inventory of facts and myths about whales, a

concatenation of romance, philosophy, natural history…. It was

also an audacious attempt, long before Freud and his modernist followers,

to represent in words the unconscious as well as the conscious processes

of the human mind itself.”

“And what of the man at the helm?” Delbanco

asks. Ahab is one of the most original characters in the history of

literature. He is the first appearance in literature of the modern

demagogue, “a prophetic mirror in which every generation of new

readers has seen reflected the political demagogues of its own times.”

Melville’s achievement came as his reputation

plummeted. The books from his middle period sold poorly. Readers wanted

the light-hearted adventure of the South Pacific found in his earlier

works, not allegorical epics about whale hunting. Many unsold copies

of the first U.S. edition of Moby-Dick were remaindered and

then lost to a fire in the publisher’s warehouse. Melville resorted

to magazine writing, living off the largesse of his in-laws, and working

as a New York customs house inspector for the last decades of his life

His personal life spiraled downward, along

with his writing career. He was moody in temperament, capable of enthusiasm

and energy, but prone to sudden downswings and withdrawals. These outbursts

alienated his wife and four children, especially his sons. Melville

would suffer the ghastly fate of outliving both his boys: Malcolm,

who committed suicide at eighteen; and Stanwix, who died in poverty

at thirty-five.

In this dark period, Melville achieved artistic

triumph. He published two of the greatest short stories in the English

language. “Bartleby the Scrivener,” Delbanco believes,

anticipates Kafka and existentialist literature by decades, grappling

with an un-resolvable tension between “the moral truth that we

owe our fellow human beings our faith and love” and “the

psychological and social truth that sympathy and benevolence have their

limits.” In his 1855 novella Benito Cereno, Melville

explores race and slavery by inverting the relationship between a Spanish

slave-ship captain and his African cargo.

Melville also wrote one last tale, left unfinished

and orphaned when he died. Discovered in a tin breadbox, Billy Budd,

Sailor was published in 1924, three decades after Melville’s

death. Twentieth-century writers such as E. M. Forster, Albert Camus,

and Thomas Mann regarded Billy Budd as Melville’s masterwork,

one of the most beautiful stories ever written. Generations of readers

have been touched by the doom of the Christ-like Billy, but for Melville,

Billy’s death is the inevitable consequence of the conflict between

society’s laws and natural justice, between the individual and

society.

Delbanco’s writing is blessedly free

from academic theory, and Melville is good biography and great

literary history.

Pasco Gasbarro is a book-review editor for this

magazine.

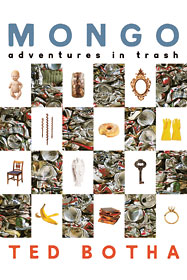

Adventures in Trash

Adventures in Trash

By Ted Botha

New York: Bloomsbury, 2004

243 pages. $23.95

ISBN: 1582344523

According to Cassell’s Dictionary of

Slang, the word mongo was coined in New York in the 1980s.

It refers to trash, or more specifically, to treasure found in trash:

books, artifacts, furniture, even food. Ted Botha’s book explores

a whole culture, and various subcultures, that revolve around mongo.

Those obsessed with mongo often live on the

margins, sometimes by choice, sometimes by misfortune. The “canner” who

collects aluminum cans and glass bottles out of others’ garbage

bins for recycling, says Botha, is looking for mongo, as is the old

woman driving around the city, examining discarded and often broken

furniture on the sidewalk. They may be unemployed, addicts, or psychologically

disturbed; or they may be quiet citizens from the suburbs, enthralled

by the quest.

Botha classifies mongo collectors into different

types. “Pack rats” scour and accumulate for accumulation’s

sake. “Survivalists” look for high-quality mongo, like

used bed sheets rejected by wealthy Long Island households that can

be resold at the flea markets and sidewalk sales of Manhattan. “Anarchists” live

off the excess of restaurants and groceries, scavenging food from cartons

and garbage bins. They’re usually younger people who are involved

in anticonsumer and antiglobalization movements and subsist in the

precious few low-rent spaces left in Manhattan. “Visionaries” assemble

street-found mongo into ingenious works of art and interior décor

that belies their trashy origins.

Most book collectors have seen the eccentric

and disheveled devotees of mongo who lurk at the edge of the book trade

and salvage treasures, which end up on the shelves of more respectable

dealers and in private and institutional libraries. Botha’s chapter “The

Dealer” profiles Steven, a street bookseller whose stock consists

of discarded books and magazines found among the garbage of museums,

luxury apartment buildings, estate sales, and failed stores. He makes

remarkable finds and lives by a code of rules that exemplifies guerilla

bookselling, such as “Good books can turn up where you least

expect them” and “Time spent looking for the right buyer

could be worth a lot of money.” Some of these rules also reflect

the hard life of mongo collectors existing on the edge of society: “Never

get too attached to a book, or for that matter, to anything” and “Most

people think that if you collect off the sidewalk, you’re a bum.”

There are profound characters here, and Botha

is sympathetic to many of his subjects, but he doesn’t dig deep.

An admitted mongo aficionado, he’s more interested in the uses

of mongo—especially for art and interior design—than the

stories behind the people who collect it.

Pasco Gasbarro

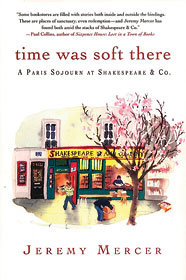

Time was Soft There

A Paris Sojourn at Shakespeare & Co.

A Paris Sojourn at Shakespeare & Co.

By Jeremy Mercer

New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2005

262 pages. $23.95

ISBN 0312347391

Time Was Soft There pleasantly surprised

me, as much as life surprised its author. Mercer, who started his career

as a journalist in Canada, found himself under a vendetta from a thug

whose crimes he had reported. He fled to Paris and, not unlike scores

of writers and artists who make a pilgrimage to the city, found himself

out of work and homeless. Running out of money, he was offered a bed

and a job by George Whitman, the proprietor of Shakespeare & Co.,

the legendary bookstore on the Left Bank. Mercer, who has a journalist’s

crisp style and a good eye for human details, recognizes the real story

is Whitman’s.

Whitman opened for business in 1951 and sometime

later took the name of Sylvia Beach’s Paris store, which had

played host to a bevy of now-famous writers between the world wars.

For fifty years he has hosted authors and artists (offering them a

bowl of soup and a place to sleep), promoted promising careers, and

instigated various causes liberal and profane. The list of writers

who visited and hung out at Shakespeare & Co. is a Who’s Who of

twentieth century literary history: Henry Miller, Anaïs Nin, Richard

Wright, the Beat writers, the Paris Review crowd, and Samuel

Beckett, among others. Whitman says he and Beckett mostly sat and stared

at each other.

Mercer worked in Shakespeare & Co. for

nearly a year, becoming enmeshed in the egos and eccentricities of

this bohemian community, which harkens back to an earlier age of bookselling. “Dude,

Shakespeare and Company doesn’t even have a telephone,” his

colleagues inform him. “Of course we don’t take credit

cards.”

The book’s strength is its two main characters,

the store and its owner, and the book is best when it stays inside

the shop. Whitman’s motto is “Take what you need, and give

what you can.” His aesthetic sense is uncanny, his business sense

scatterbrained. After losing a stash of two hundred francs to a nest

of hungry rodents, he muses, “At least it’s not the books.” Is

Shakespeare & Co. really a business, Mercer wonders, and Whitman

replies, “I run a socialist Utopia that masquerades as a bookstore.”

Pasco Gasbarro

Adventures in Trash

Adventures in Trash A Paris Sojourn at Shakespeare & Co.

A Paris Sojourn at Shakespeare & Co.