Although my entry is couched in the grandiose and unqualified title “Landmarks of Classical Scholarship,” it cannot be doubted that without the foundations laid by the books in the collection and similar works in the field all the branches of the discipline of classics—the study of the arts and culture of ancient Greece and Rome—could not have grown, let alone have flourished. My collection also contains a few of the most significant contributions outside textual criticism that have greatly changed the scene of classical academia.

My overall collection of books contains some 2,400 volumes, all concerning matters of classical interest. These span the sixteenth to the present centuries, with the majority originating from the turn of the nineteenth century, when classical publications of outstanding quality emanated thick and fast from most quarters of the Western world. The majority of this library is stored around the four walls of my bedroom at home in Cumbria, although additional space has now had to be sought elsewhere. Some nine hundred books—the most essential part of my working library—surround me as I study in Cambridge. I greatly look forward to the day when a single room can house the whole of my collection.

I have built up my library over the past three-and-a-half years, having begun from scratch. My family has always had a quiet respect for books but doesn’t have a house library to speak of nor any interest in Latin and Greek classics. My fascination with books was excited primarily by visits to institutional libraries around the country during my teenage years. Although my interest in books can be traced back a good number of years, my collecting began only recently because in my hometown among the mountains, bookshops, let along antiquarian ones, are hard to come by.

The important parts of my library fall into the following, continuously expanding subcollections: editions of and works about Lucretius, modern verse written in the classical languages, the history of classical scholarship, letters and manuscripts from important classicists, and association copies from the libraries of noted classical scholars. More than a thousand additional books cannot be categorized in the above groups. These books range from standard editions of Latin and Greek poets, orators, historians, and philosophers to facsimiles of manuscripts and paleographic hands (ancient handwriting), analytic commentaries, grammars and lexicons, and all kinds of peripheral material, such as offprints of important nineteenth- and twentieth-century articles.

It is perhaps worth saying a few words about myself as a collector. I believe I possess not only an uncommon interest and passion for collecting antiquarian books but also the resources and ingenuity for the task of actively hunting down the most elusive desiderata. I have often gone to great lengths to acquire some of the items I own. I have, for example, learned basic Danish to charm a Scandinavian bookseller into a price reduction, and I bought and sold the 1516 Aldine edition of Ovid’s Metamorphoses in order to cover the costs of purchasing a yet more important book. I have also spent many hours searching all corners of the Internet for bargains. Since I am hunting Latin and Greek classics, and since booksellers often misspell titles (or leave the author’s name in the genitive case), many excellent purchases can be made at the expense of a seller’s lapsus digiti. The auction site eBay certainly provides an excellent tool for the book buyer, and I have often woken up in the early hours of the morning to win an overseas auction at the last minute. I have made many trips to cities, including those of foreign or even classical lands, for the sole purpose of scouring bookshops, often testing the patience of many a bookseller by asking to look through their items hidden away behind glass. I can ask for a specific type of book in Modern Greek more fluently than I can ask for a beer.

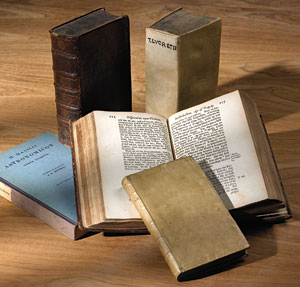

It is a fair question to inquire how, financially, it has been possible for me, at the age of twenty-one, to obtain a library larger than most other people’s. I have no independent wealth, so I have had to seek funds through the traditional routes. I have won a number of university prizes and scholarships on academic grounds, the money from which I have directed into building and extending my library. I have also coedited a forthcoming Latin dictionary for the publisher Penguin, the money from which has aided my bibliophilic urges. Importantly, I have very rarely bought an antiquarian book at anything near its “worth,” but rather I continually seek bargains (an increasingly difficult exercise) and believe it is the first principle of building a library that content should override condition. I go weak at the knees for fine bindings as much as the next person, but I see more gold in a tattered copy of a scholar’s magnum opus than in a sumptuously produced and beautifully preserved volume that possesses no interest independent of that. My library reflects this catholic approach to seeking material, which has facilitated my forging a collection that already holds significant breadth and depth.