Creative Destruction and the Photography Revolution

As accurate imitation of nature became the unchallenged domain of the photograph, artists explored how painting could move beyond the old ideal of “holding a mirror up to nature.” As photography superseded painting as a representational art form, painting would break new ground as a creative one.

Portrait painters, less able to roll with artistic currents, thought photography would put them out of work. Most, in the end, would find a career in hand-coloring photographs. Harper’s Weekly described the shift in 1857: “The vocation for the portrait painter is not gone but modified. Portrait painting by the old methods is as completely defunct as is navigation by the stars.”

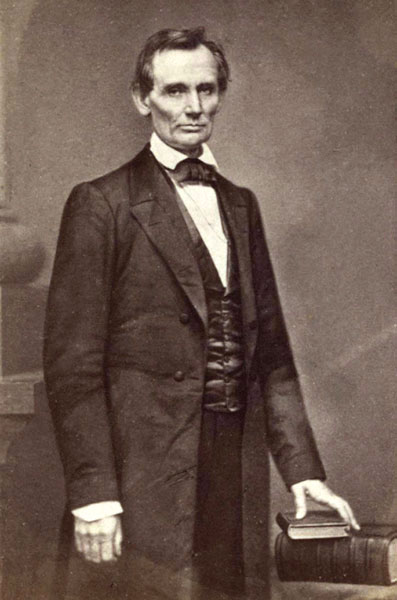

Photography played a role in the era’s destabilization of traditional class relations as well, democratizing access to “the portrait,” which for centuries had been an important marker of status, accessible only to a tiny elite. Photography made portraiture accessible to almost everyone, especially to the burgeoning middle class, whose tastes and desires would increasingly shape nineteenth-century societies. The craze for card-sized portraits (figure 4) in the 1860s and 1870s became a hallmark of how the ascendant middle class presented itself to the world.

Photography transformed the world of politics, helping to elect Abraham Lincoln president—according, at least, to Lincoln himself, who gave partial credit for his 1860 win to the photographer Mathew Brady. Alluding to the picture seen here (figure 5), taken after Lincoln’s famous Cooper Union speech, Lincoln said, “Brady and the Cooper Institute made me President.” Lincoln’s campaign button was also the first to feature a photograph.

Photography also profoundly changed our nation’s perception and understanding of war. Romantic notions of the heroism of war were more difficult to maintain as the mounting casualty numbers from the Civil War were brought home with photographs like Home of a Rebel Sharpshooter (figure 6) by Alexander Gardner.

One of the most interesting aspects of curating this exhibition was the detective work it required. Most nineteenth-century photographs come to us mute, without captions or descriptions, unsigned, undated, and anonymous, both in terms of the photographer and its subjects. One learns to date an image based on subtle clues: the style of a dress, sleeves, facial hair, or a combination of those things. One begins to recognize a Mathew Brady portrait by a specific carpet, which appears in several of his shots.