Projecting the Empire

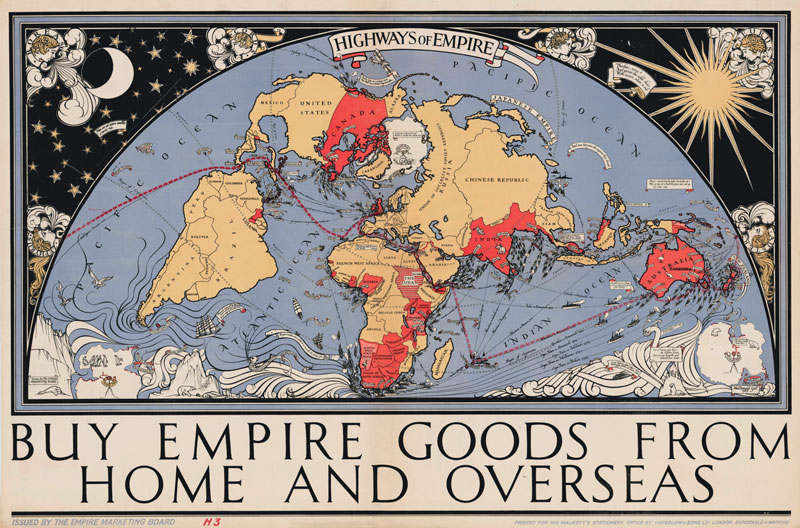

Gill’s poster map was originally intended for display through existing commercial sites, and about three thousand copies were printed in forty-eight sheets to fit twenty-foot by ten-foot billboards. But the cost of renting these sites proved not only prohibitive but limiting as well, since most cities in the United Kingdom regulated their number and location. Consequently, a poster-size edition of the map was quickly put into production in early 1927. This smaller version could be displayed for free by retailers in their shop windows, especially during Empire Shopping Week.

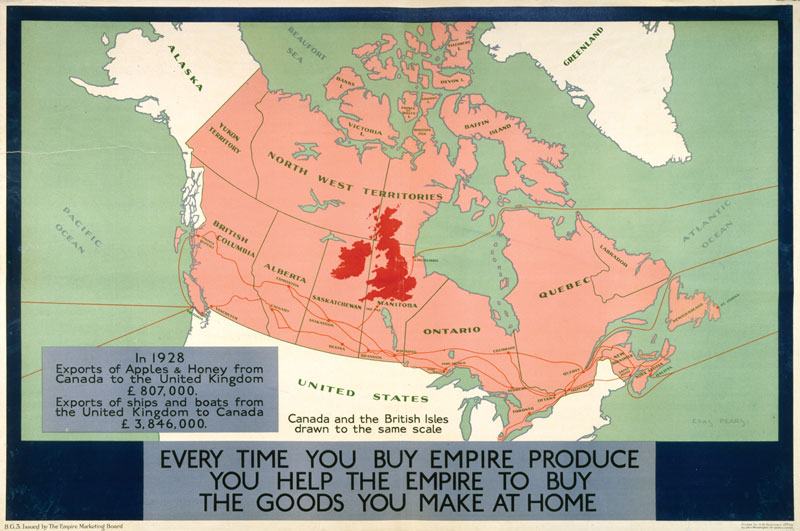

Gill’s map aside, the EMB posters that generally attracted the most attention were produced in multiple sets and were displayed in the Board’s own frames, of which some seventeen thousand were set up in public areas across the country. The frames were made from English oak and measured about twenty feet long and five feet high. They were organized into five panels: three large and two small. The two smaller panels often carried cheaper letterpress messages that linked the three large lithographed posters together into a common theme. Often the center panel in the display was a map that conveyed some little tidbit about Empire trade. So as to keep these posters in the public eye as much as possible, the EMB changed them about every three weeks.

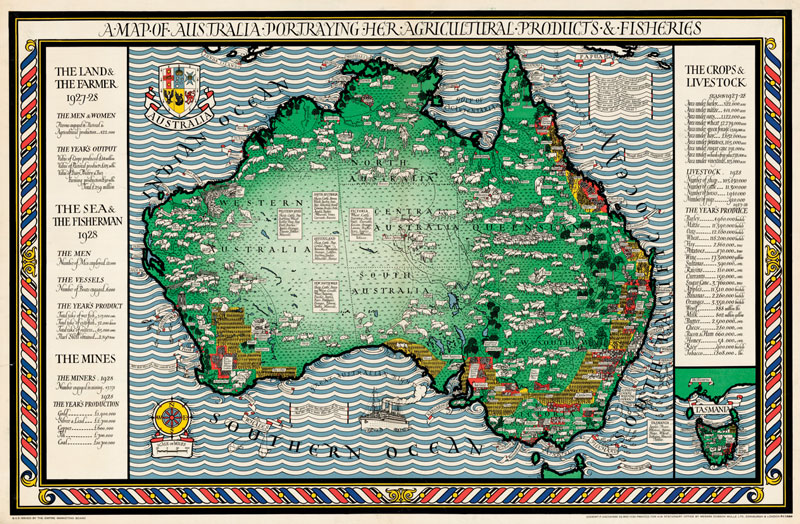

The Board was well aware of its unique role in conveying the “dignity” of government and went to considerable length to commission maps and other artwork of the highest quality. Good design was not an option but a necessity to “move the hearts and minds” and bring “the Empire alive,” as one contemporary advertising critic put it.

The importance the EMB placed on good design, historian Stephen Constantine points out in Buy and Build, is evident in the commissions paid to its artists. In an era when seven hundred pounds would buy a nice three-bedroom semi-detached house on the outskirts of London, the EMB paid as much as three hundred for a full set of five posters. Gill’s single map, Highways of Empire, earned him a handsome £157. It also enhanced his reputation. The EMB was so inundated by requests from schools for copies of the map that several additional print runs were ordered. The Board sold these extra maps at cost along with a separate booklet describing the ocean highways Gill highlighted.

Even two years after it was issued, public demand for Gill’s map still exceeded the Board’s supply. In one 1929 exhibition sponsored by Schoolboys’ Own, the EMB had twenty-six thousand copies of Gill’s map ready for handout, but one hundred thousand visitors mobbed the display, knocked down the rails, and caused the Board to close its booth.

The public also heavily endorsed other poster maps published by the Board. One, which also featured the Empire, was described by British teachers as a “wonderful help both in Geography and History lessons,” “admirable for illustrating school geography,” “a splendid means of showing our boys … the links of Empire,” and “invaluable for British Empire lessons.”

Despite its well-received advertising campaign, critics found the EMB to be little more than a relic of an old colonial mentality. In a speech to the British Press Association, one Canadian parliamentarian, C. A. Dunning, called it “a completely outdated idea.” Why would self-governing dominions like Canada, Australia, New Zealand, or South Africa want to raise raw materials for British industry, when they could just as easily used those products to create their own industry? What the Empire really needed, said Dunning, was a transfer of British manufacturing skills and good old industrial know-how.

Dunning’s sentiments gradually gained in popularity across the Empire, and in 1933 the EMB was ordered closed by Britain’s Parliament. With the nation facing its greatest economic depression in history, the EMB’s substantial budget was to be put to other uses. Imperial trade would still be encouraged, but through a system of preferred tariffs rather than a subsidized marketing campaign.

When the EMB ceased operations, it left behind a legacy of more than eight hundred different poster designs. More importantly, the seven-year campaign had single-handedly changed the hearts and minds of British consumers. “Five years ago women did not know much about Empire products,” observed the London reporter for the Sydney Morning Herald. “But now they ask straight away … and woe betide the shopman who cannot produce … Empire products.”