Between the Pages of a Book

Extra-illustration on exhibit at the Huntington Library By Lori Anne Ferrell Lori Anne Ferrell is professor of early modern history and literature at Claremont Graduate University and director of its program in early modern studies. She is the author, most recently, of The Bible and the People (Yale University Press). Illuminated Palaces will be her second exhibit at the Huntington Library.

The closed stacks are neither warm nor particularly well lit. In fact, it’s eerie in here, especially since I have no way to get out. (Well, there goes one academic’s fantasy.) I am only the guest curator, so I am not allowed keys to the important rooms that hold the Huntington Library’s rare books and manuscripts. I have been locked into this area for an hour in order to evaluate potential items for an exhibit titled Illuminated Palaces: Extra-Illustrated Books from the Huntington Library. I am alone.

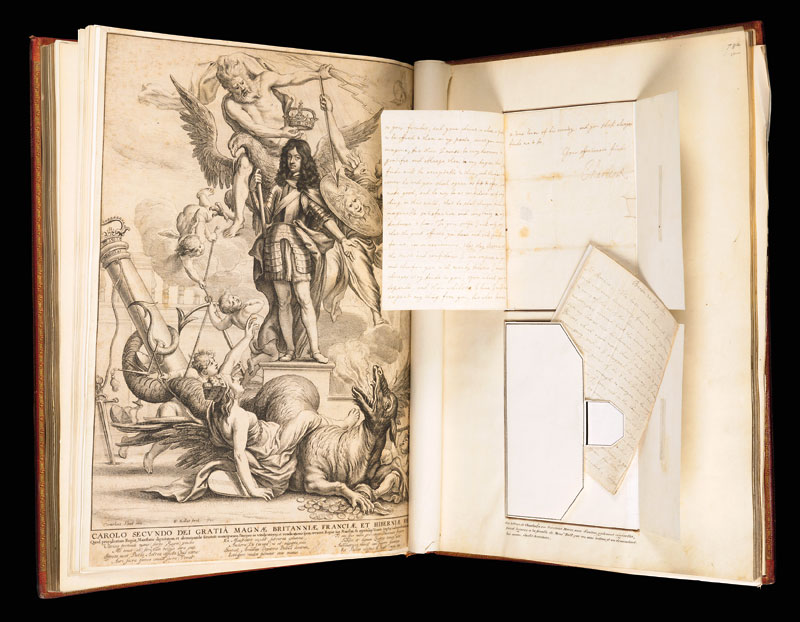

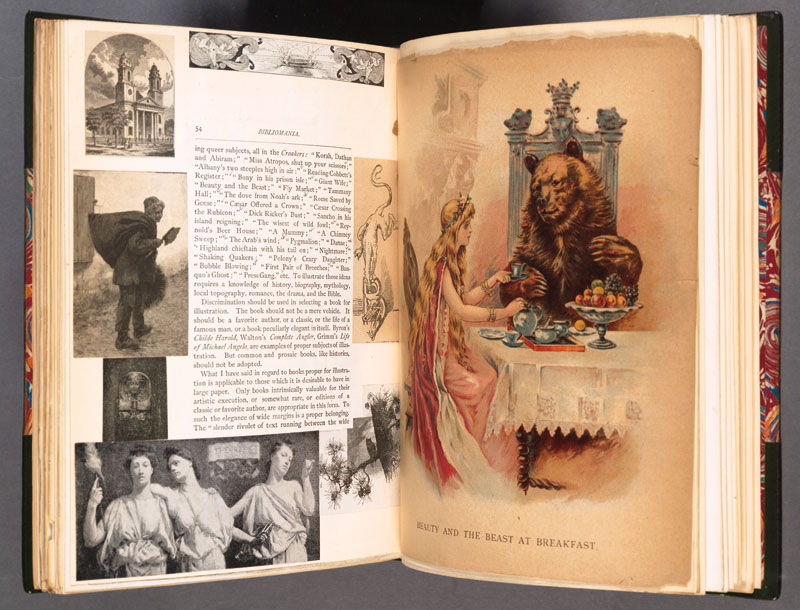

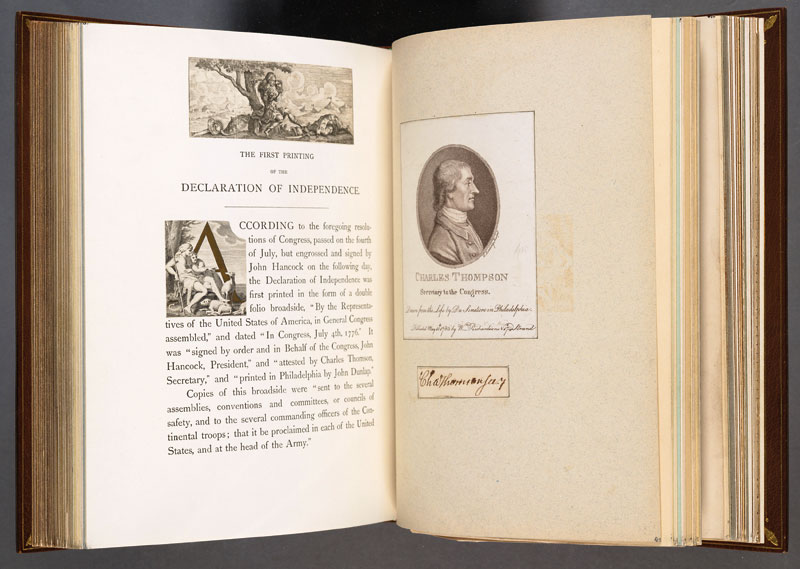

Well, not exactly. There is a stunning folio propped on the cradle before me: volume one of Grammont’s Memoirs, a racy firsthand account of the court of King Charles II of England (1660–1685). Like most of the Library’s more than one thousand “Grangerized” books, Memoirs was acquired in the first half of the twentieth century and has not been catalogued. This copy was extra-illustrated by the indefatigable print collector Richard Bull (d. 1806), and so I should feel anything but alone right now: its pages are crowded to bursting with hundreds of portrait “heads,” making passages from this account of the amorous intrigues of England’s “merry monarch” seem like so many parties on a page. One unusual opening catches my eye. At left, a striking double-folio political engraving of the king has been tipped in, folded in half to fit. (I open it and think, handsome devil; no wonder you were so merry.) At right is something less decorative and more mysterious: a folio sheet on which are glued two handmade envelopes. I pry one open and pull out a letter written by King Charles II. I stop breathing for a moment, regain control of myself, and open the second envelope. It contains another holograph letter by the king.

In real life, I teach, research, and write about early modern English literature and history. To people like me, letters like these constitute archival evidence, not showpieces. And so, after this exhibit closes, these two letters will part company with the book that has hidden them for over two hundred years. They will be properly catalogued (as will the book) and placed into the safekeeping of the department of manuscripts. Historians of Restoration Britain will travel to San Marino, California, to study their contents. Right now, however, I don’t have time to read. I am anxiously conferring with my senior partner on this project, the Huntington Library’s curator of early printed books, Stephen Tabor, about whether we can put this extraordinary opening in the exhibit.

Stephen thinks the conservator and exhibit designer can be persuaded to construct the kind of props that will allow us to safely display the unfolded print extending out from the right, the envelopes on the left, and the letters out and open. But it’s by no means a sure thing; research libraries like the Huntington are charged to conserve as well as provide access to rare books and manuscripts, and we don’t know whether such a set-up will be too damaging to be sustained over the course of a four-month exhibit.

In other words, it’s just a typical day working with those singular treasure troves known as “extra-illustrated books.”