Covering Walker Evans

An exhibit explores the intersection of fine art photography and book cover design By Andrea L. Volpe Andrea L. Volpe writes about American photography and culture. She has written for Cognoscenti, The New York Times, and Afterimage and is finishing a book about American cartes de visite and photograph albums during the Civil War. Find her at andrealvolpe.com and follow her on Twitter at @andrealvolpe.

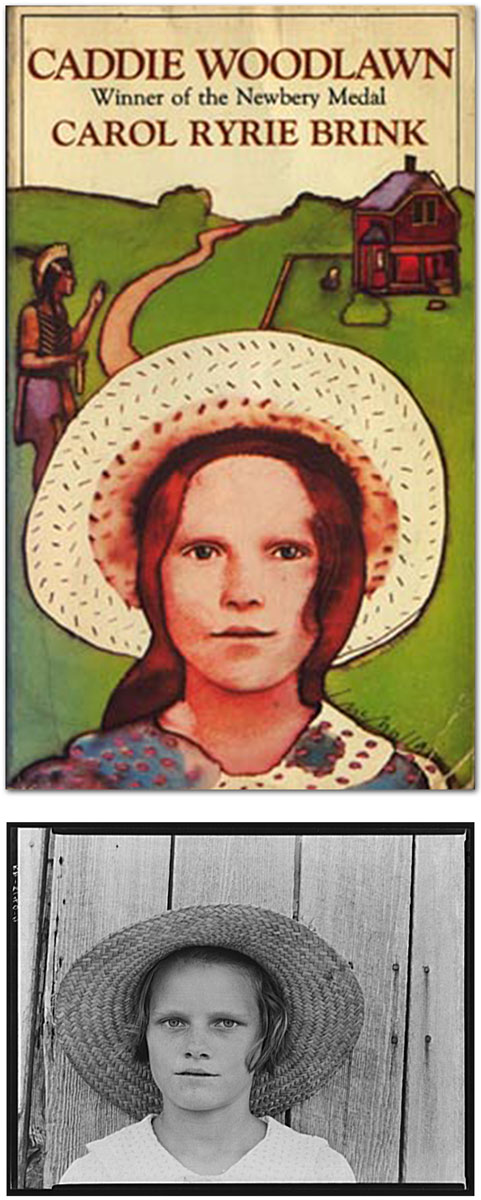

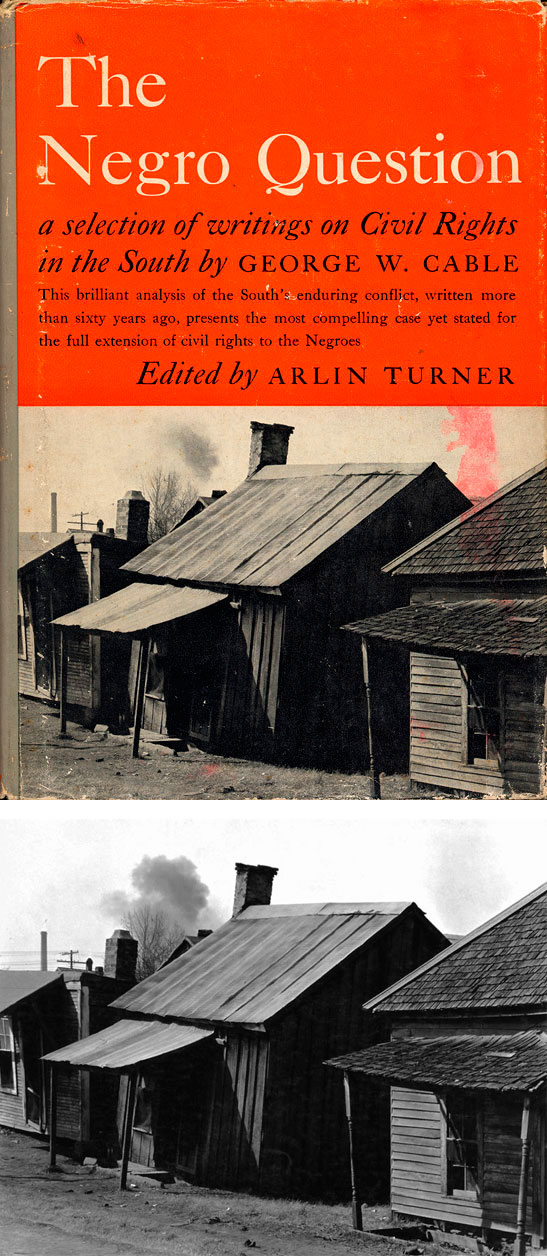

Covering Walker Evans, an exhibit of books whose covers are illustrated with—but are not about—Evans’ photographs, examines what happens to the fine art photograph when it becomes a metaphor for a book’s contents. Curated by photographer Karl Baden from his collection of secondhand titles, the show is at Harvard University’s Carpenter Center for the Visual Arts through August 31.

The thirty-six books, ranging from literature, sociology, and history, show how Evans’ images were appropriated as illustrations beginning in the 1950s. They are a small selection of a larger collection—between four and five thousand books—whose covers either reproduce or riff off of fine arts images (see it online at CoveringPhotography.com). “It interests me that I’m doing something that I don't necessarily trust, which is buying the book for its cover,” Baden said.

The collection comes from years of bookstore browsing. “I started doing this in about 2000. I have an affinity for the history of photography; I've done a number of projects on it, so it's always on my mind and it’s the way I think. It started when I was going to bookstores looking for photobooks that I didn't have. Mostly I didn't find them, but I did start finding these. I started putting a collection together and as I brought the books home, I had more ideas because of the connections that I was making.” Those connections were about the way photographs change through time, culture, and context. The books themselves are the evidence of this process. "I like the fact that they are used, I like it if they have writing in them, I like the provenance," Baden said.

Baden’s collection couldn’t be more antithetical to the photobook. But his exhibit speaks to the way Evans’ American Photographs, made alongside his one-man photography show at the Museum of Modern Art in 1938, influenced photography. That exhibit, which drew in part on Evans’ Farm Security Administration (FSA) photographs, shifted the photograph from document to fine art. The almost square book, with an essay by Lincoln Kirstein, included eighty-seven photographs with the verso sides left blank. There was no text save an index. Part I offered an unsentimental, collective portrait of America through its people and institutions. Part II presented carefully framed views of vernacular architecture. Evans’ spare style became more apparent with the turn of the page.

American Photographs established the photobook as an art object and Evans as the preeminent American photographer. Evans encouraged Robert Frank to take the road trip that lead to The Americans (1958). Influence unfolds from there: Ed Ruscha’s Twentysix Gasoline Stations (1963), Lee Friedlander’s The American Monument (1976), William Eggleston’s Guide (1976), and Stephen Shore’s Uncommon Places (1982), right through to Alec Soth’s Sleeping by the Mississippi (2004).

Baden’s collection poses a question: what happens to photographs when they become art, after, and because of, the photobook? It also gives an answer: in print, photographs are mobile and reproducible; they can shift meaning, loaning it out to other contexts. But when context shifts, meaning shifts too—photographs, despite their documentary claims, are malleable.

Evans’ photographs are an ideal case study. FSA photographs, held by the Library of Congress, cost nothing to reproduce and are immediately recognizable. “If you're going to do a book about the Dust Bowl or something like that,” Baden explained, “chances are you're going to use a FSA photographer.” See an Evans photograph on the cover and you expect a match between the picture’s content and the book’s subject. “But once you get into poetry, fiction, memoir,” he said, “it becomes less literal and more metaphoric.”

The metaphoric use of a photograph could signal that a book’s text, like photography more generally, is objective. It could also evoke aesthetic affinities—what’s between the covers is as lyrical as an Evans photograph. Baden’s point is that a fine art photograph on a book cover always signals cultural transformation: putting a photograph, made to challenge the very definition of art, on the cover of a book turns the image into a cultural icon. It may look like the same photograph, but it’s not. “Form remains the same but the content changes,” Baden said.

We all have books with covers like this on our shelves. A quick Internet search of “Walker Evans cover photograph” reveals numerous results, with familiar thumbnails. They are the measure of the fine art photograph’s influence in American visual culture.