Along Came Lund

When an unclaimed trove of manuscripts and self-published books stored in a Detroit warehouse came to light, the dark side of magician Aleister Crowley roused collectors—and kooks By David Meyer David Meyer is the author of Memoirs of a Book Snake: Forty Years of Seeking and Saving Old Books.

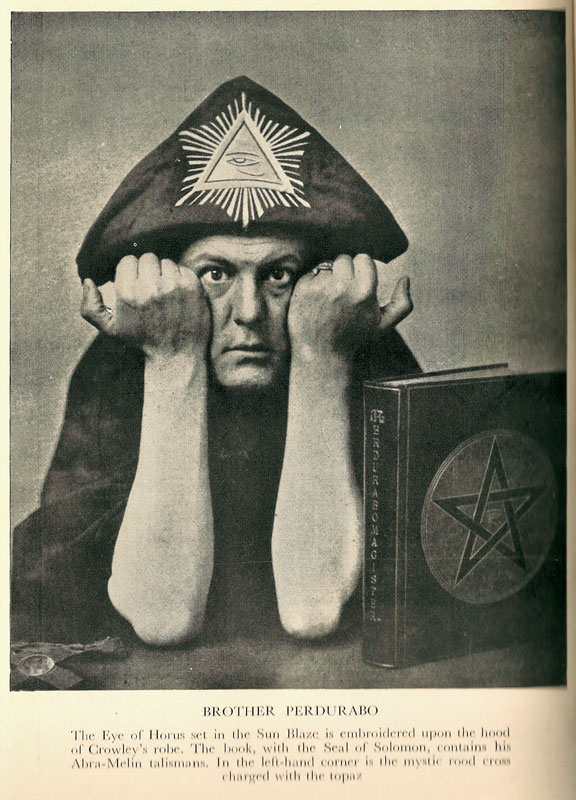

Aleister Crowley appropriated the number “666.” Reference to him as a beast was said to have originated with his unloving mother. He was, to quote the curator of an exhibition on black and white magic at The Peabody Institute Library, “a remarkable Englishman who was a poet, writer, painter, and athlete … but best known as a practitioner of devil worship and black magic. His practices were so notorious that he was commonly referred to by his contemporaries as ‘The Great Beast.’”

Think “crow” to pronounce Crowley’s name correctly, although, unlike crows, he was migratory most of his life. He hiked across China; climbed K2, the second-highest mountain in the world (although he didn’t reach the summit); spent two years roaming India; had his “first mystical experience” in Stockholm; and became a Thirty-Third Degree Mason in Mexico—all by the time he was twenty-seven years old.

He met Somerset Maugham in Paris in 1904, which led Maugham to write The Magician, a novel that included this passage alluding to Crowley: “There was always something mysterious about him, and he loved to wrap himself in romantic impenetrability. … A legend grew up around him, which he fostered sedulously, and it was reported that he had secret vices which could only be whispered in bated breath.”

Maugham was writing fiction, but it was based on what he knew of Crowley. In an introduction to a reprint of the novel, Maugham expressed a more critical opinion of Crowley, saying, “I took an immediate dislike to him, but he interested and amused me. … He was a fake, but not entirely a fake. … He was a liar and unbecomingly boastful, but the odd thing was that he had done some of the things he boasted of. … At the time I knew him he was dabbling in Satanism, magic and the occult.”

Crowley (1875-1947) developed a reputation for wreaking havoc on those would-be believers in the mystical and occult who came under his influence. All his life was complicated by associations he formed, secret organizations he joined or created, followers he corrupted and used, wives he seduced and stole.

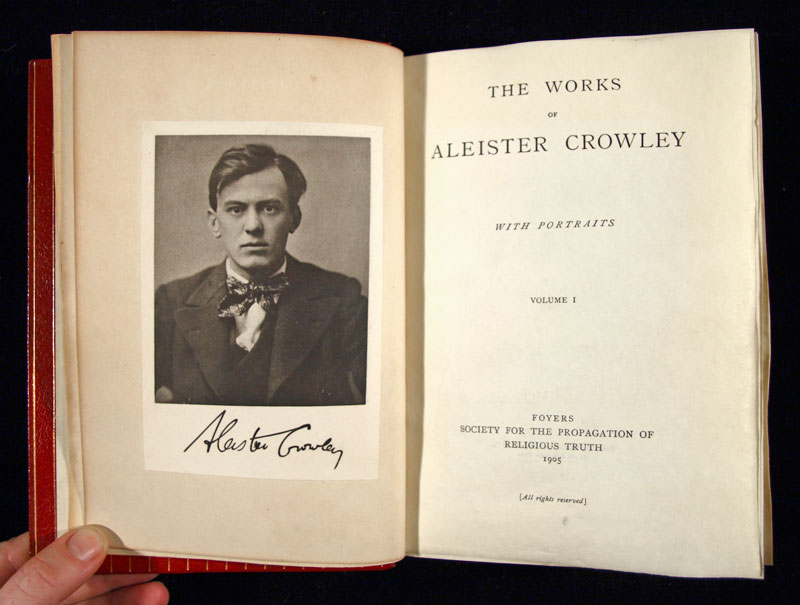

He had been self-publishing poetry, fiction, erotica, and essays since the late 1890s. Much of this was financed by an inheritance from his parents that was estimated at 40,000 pounds, equivalent to approximately $200,000 at the time. By 1914, however, when he came to the United States, he was reported to be nearly bankrupt. He brought with him personal copies of his manuscripts and books. Titles of a few allude to their contents, such as Alice: An Adultery (1903) and Jezebel and Other Tragic Poems (1898). Other titles suggest more obscure subjects: Alcedema: A Place to Bury Strangers In (1898) and Bagh-I-Muattar: The Scented Garden of Abdullah the Satirist of Shiraz (1910), an erotic novel noted in a Crowley bibliography as having been issued in 200 copies, “the bulk destroyed by H.M. Customs in 1924.”

This personal collection, variously described as being carried in two trunks or cases, consisted of approximately 125 titles, many the same but in different formats. Ahab and Other Poems, for instance, was privately printed “from a Caxton font of antique type” at London’s Chiswick Press in 1903. Crowley brought three copies with him: one (of only two copies) printed on vellum, one (of only 10 copies) printed on Japanese vellum, and one (of 150 copies) printed on handmade paper. He also had the holograph manuscript and the original typed manuscript with corrections in ink and pencil in Crowley’s hand—bound in three-quarters leather over marbled boards with raised bands. In fact, most of the typeset works in Crowley’s personal library were printed on vellum; these and a number of his manuscripts were luxuriously bound in full leather, some with silk endpapers, by the famous London bindery Zaehnsdorf.