Along Came Lund

His hope was to sell his so-called “rariora” to John Quinn, a New York attorney, art patron, and book collector. Quinn was known for buying manuscripts from contemporary authors whose work he admired. Quinn came to own the manuscripts and typescripts of twenty four works by Joseph Conrad, James Joyce’s original manuscript of Ulysses, and drafts of works by William Butler Yeats, William Morris, Robert Louis Stevenson, Ezra Pound, and many others. However, his purchases from Crowley were probably disappointing. When Quinn’s collection was dispersed, between November 1923 and March 1924, a five-volume auction catalogue was prepared offering 12,108 lots, which were sold in 33 sessions. Of the 67 lots of Crowley books and manuscripts in the sale, only 20 were likely to have been purchased directly from Crowley.

Crowley remained in the United States until 1919, moving from place to place, often staying for only short periods of time to establish contacts with members of a Masonic-related organization variously known as the O.T.O. or Ordo Templi Orientis or Order of the Oriental Templars or Order of the Temple of the East. When the O.T.O. came under Crowley’s leadership its stated beliefs became “Do what thou wilt shall be the whole of the Law” and “Love is the law, love under will.” Free love, purported orgies, and ruined lives and livelihoods were reported in published accounts of the group’s activities.

Crowley arrived in Detroit in 1918, bringing his rariora with him. While in New York he had met a prominent Detroit businessman and Mason named Albert W. Ryerson, who agreed to distribute the trade editions of Crowley’s many self-published books and to publish his journal, The Equinox. Another reason for Crowley’s coming to Detroit was to visit the drug manufacturer Parke-Davis and Company, which was preparing a batch of peyote extract that Crowley intended to use in O.T.O. rituals. Although accounts differ as to why Crowley stored his personal collection in a Detroit warehouse, there it remained, unclaimed, for nearly 40 years.

“Many people leave books in warehouses,” Robert Lund said in 1983.

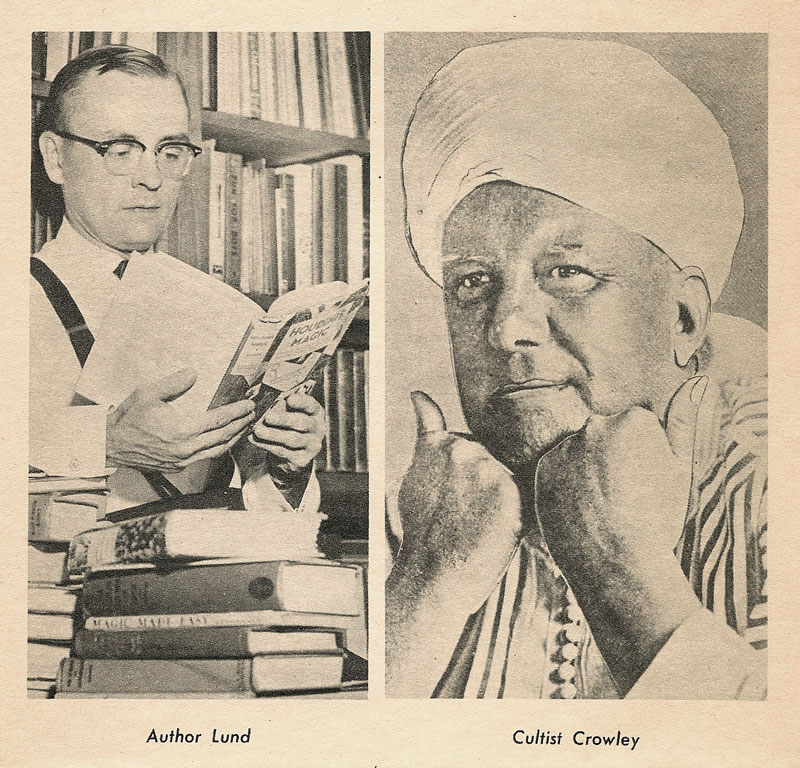

He was being interviewed by author Martin Starr, a member of the Illinois Masonic Fraternity who was researching aspects of Crowley’s life that had never been adequately explained. Lund, he learned, had purchased Crowley’s personal library, and the first question asked was how and when the material was discovered.

“This would have been about 1955 or ’56,” Lund replied, although he was incorrect regarding the date, which is not surprising considering that he was attempting to recall an event that had occurred twenty-five years before.

Workers in the Leonard Warehouse in downtown Detroit “came across some books in beautiful bindings and some manuscript material,” Lund said. “The owner of the warehouse was not about to throw this stuff away. He called in a book dealer, who offered him two hundred, two hundred fifty, some such sum. … This alarmed the owner, because he had never been offered such an amount of money for some old books. He called the curator of rare books at the Detroit Public Library.”

At this point in the interview, Lund and his wife scoured their collective memories to remember the curator’s name—Frances Brewer, it was—who told the warehouse owner she’d find out who Aleister Crowley was and call back. When she did, according to Lund, she told the warehouse owner, “The man who is an authority on magicians is a friend of mine. His name is Bob Lund. Why don’t you call him?”

Lund began his career as a newspaper reporter in Detroit and later became an auto industry columnist for Hearst Publications. He was also an amateur magician and ardent collector of magic—the performing kind—and sought everything relating to magicians’ tricks and careers. “I want it all,” he used to say, and he meant it. Over a period of fifty years, through correspondence with magicians and fellow collectors, and by purchases of posters, publicity materials, scrapbooks, periodicals, and books, Lund’s collection grew to be one of the largest ever assembled on the subject. Every letter, postcard, news clipping, photograph, and item of ephemera that reached him was kept and carefully filed. The collection became so extensive it filled Lund’s home and garage in Southfield, a suburb of Detroit.