Along Came Lund

The monetary difference was not as substantial as it seemed, considering the fact that Kaplan was selling his entire collection to the university, not just the items he obtained from Lund. More importantly, it was Lund alone who had the greater pleasure of acquiring the long-lost library of Crowley. He confirms this in a final letter on the subject to Marshall:

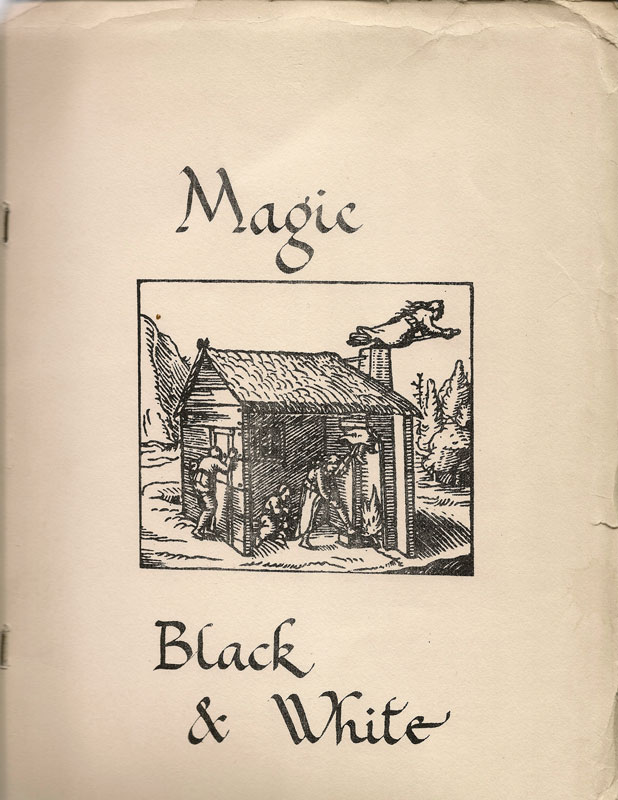

“Magic Black and White”—the exhibition held at Baltimore’s Peabody Institute Library in 1960—included items loaned by Lund and Kaplan. For the “Sorcery” section of the show, Kaplan contributed five photographs of Aleister Crowley. One of these was in his role as “Master Therion,” one of Crowley’s assumed spiritual titles, and another “in magical robes with uraeus serpent crown and magical paraphernalia, including the stole of revealing.”

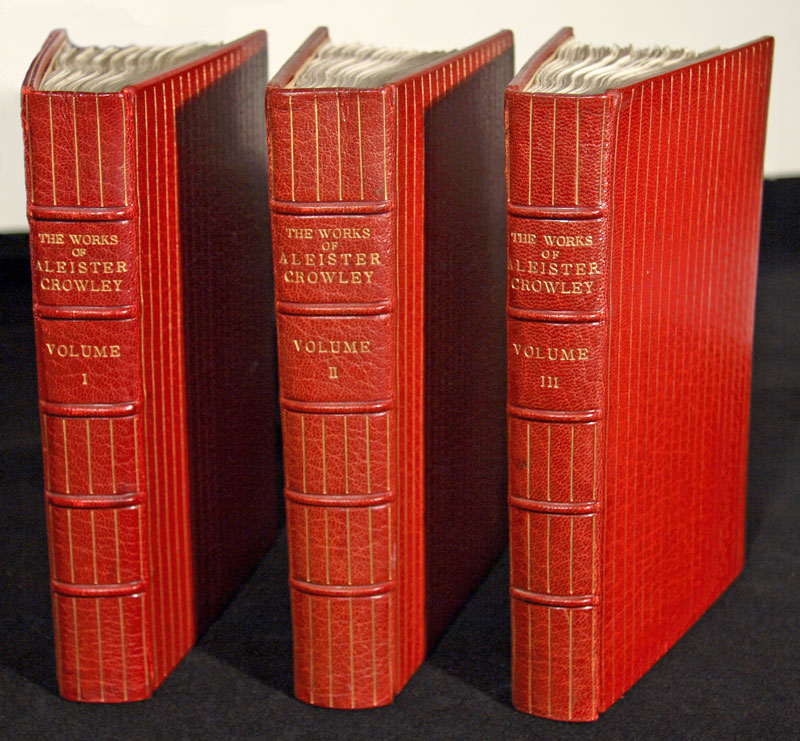

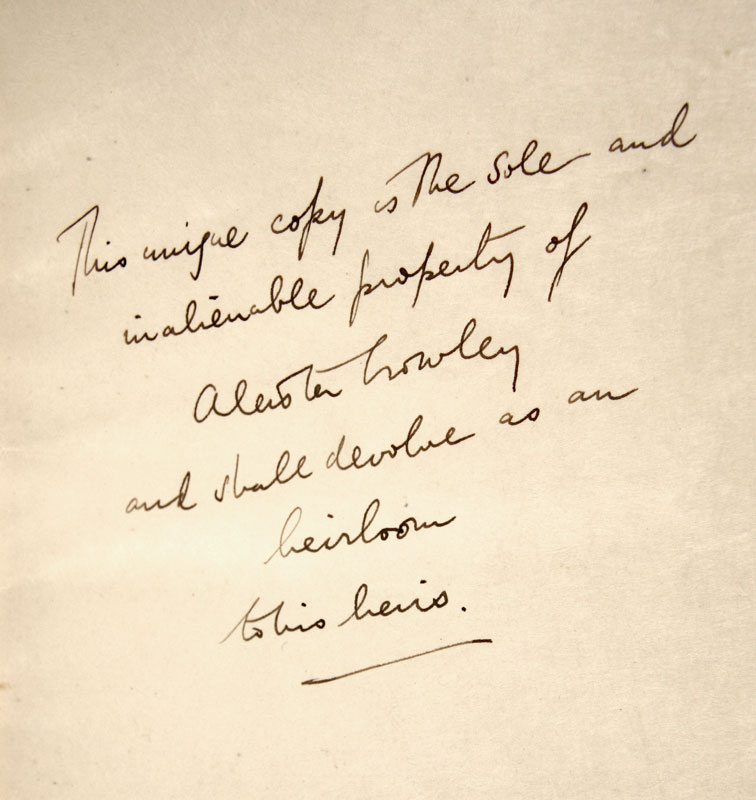

Lund loaned two books that he had not sold to Kaplan: The manuscript of Crowley’s Book of Lies (1913) and The Works of Aleister Crowley, a three-volume collection, each volume published individually from 1905 to 1907. The set is printed on vellum and bound in red morocco with gilt stripes running vertically over the front and back covers and spines. Raised bands on the spines set off the titles and volume numbers. On the front free endpaper of the first volume, Crowley had written, “This unique copy is the sole and inalienable property of Aleister Crowley and shall devolve as an heirloom to his heirs.”

Many of the individual works reprinted in this three-volume set had been in the library Lund purchased. He may have kept this set as a remembrance of those original manuscripts and first editions he once owned. In the late 1980s, he sold the manuscript of Book of Lies, on my recommendation, to a rare book dealer in California—“for upwards of money,” to use one of Lund’s favorite phrases.

I had known Lund since the 1960s, when I was a teenage collector of books on magic and would call him to ask for advice. Over the next thirty-five years, we became good friends and kept in contact by letters, phone calls, and my frequent visits to his home and museum. Our conversations covered many topics, but if they strayed too long in any direction, Lund would say, “Let’s get back to the subject of magic.”

After inspecting his Crowley set in 1986, and seeing that he had tucked a card in it carrying the name and address of the California book dealer I had recommended to him, I sent him a card of my own. I requested that Bob place it next to the first card. Mine read: “David Meyer will buy this Crowley set and pay more for it than any book dealer.”

Lund died the night of one of my visits in October 1995. His widow incorporated the American Museum of Magic as a nonprofit institution three years later. After her death, I received a call from the attorney handling her estate advising me—for I had forgotten—that I could purchase The Works of Aleister Crowley.

My wife and I drove to Michigan to pick up the set of books. On the way home she said to me, “Do you realize what day this is? It’s June 6, 2006.”

666? Not exactly. But perhaps close enough for Karl Germer to believe the date was decreed by black magic.

An unabridged version of this article originally appeared in the Caxtonian, the journal of the book club in Chicago known as The Caxton Club.