Dante Devotee

Matthew Pearl, author of five bestselling biblio-mysteries with another on the way, leaped into the Inferno and never looked back By Nicholas A. Basbanes Nicholas A. Basbanes, author of On Paper: The Everything of Its Two-Thousand Year History, was recently awarded a NEH Public Scholar fellowship for a dual biography of Henry and Fanny Longfellow, to be titled Cross of Snow. His other books include About the Author, Editions & Impressions, A World of Letters, A Gentle Madness, Every Book Its Reader, Patience & Fortitude, Among the Gently Mad, and A Splendor of Letters.

I won’t suggest that the novelist Matthew Pearl’s path to becoming a bestselling author is unique in the history of American letters—very little in the realm of human events is unique, it is fair to say—though I know of no other example quite like The Dante Club, and how it was that a young man in his early twenties came to write such an appealing biblio—mystery in the first place.

The idea of even writing a work of popular fiction was not something Pearl, now forty, had thought even remotely possible when he enrolled at Harvard as a seventeen-year-old freshman in 1993. Fact is, he wasn’t even sure what he wanted to do with a “concentration” in English and American literature when he graduated (Harvard doesn’t have “majors”), which is why after receiving a bachelor’s degree summa cum laude four years later, he entered law school at Yale.

“I was not by any means driven to be a lawyer,” Pearl told me over coffee in a Cambridge café, one of several in and around Harvard Square that the father of three young children uses as a makeshift office when he’s working on a new book and needs a bit of private time. “One reason I chose Yale Law School was that it has this reputation for being free-spirited, for being different, and not having grades, so I thought it would be a productive way for me to bide my time until I figured out what I really did want to do. But it’s still law school, and I quickly found I missed interacting with books and literature and reading in the way I had in college.”

So as a diversion, of sorts, he started a little reading group with some classmates. “We met once a week,” he recalled, “and we read James Joyce, we read Kafka, we read Dante, and one of us would lead the sessions—I called my discussion group ‘Dante and the Concept of Justice.’ I also took courses outside law school, but I found that I really missed that part of my life, and at some point I came up with this idea of trying to write fiction. There was no master plan, just the material that was precious to me—and that was the Dante Club.”

“The Dante Club” he was referring to was not the novel he would proceed to write while completing his law degree, and which in due course would find a publisher and become an international bestseller, appearing in thirty languages worldwide. No, what he was recalling instead was the senior thesis he had written as an undergraduate, with a backstory that is equally as serendipitous.

While focusing on such twentieth-century poets as T. S. Eliot, Robert Lowell, and Ezra Pound, the Fort Lauderdale, Florida, native had made a “random decision” his sophomore year to enroll in a seminar that focused on Dante Alighieri (1265-1321). “I had never read Dante, and because the poets I was concentrating on were constantly alluding to, quoting, or referring to him, I thought perhaps I should take that course. I also thought it sounded like a fun experience to take a course called Inferno. Maybe part of it is that because I’m Jewish, you’re not raised thinking about hell, or believing in hell in a religious way—maybe that made it more interesting.”

Regardless of his motivation, the net result was that Pearl became “totally hooked” on Dante, and took additional seminars on Purgatorio and Paradiso, the two other canticles of the Divine Comedy, and began to study Italian. By the time senior year came around, he was sufficiently engaged that he wanted to do his undergraduate thesis on Dante. There was one hitch, however: “I didn’t have time left in my college career to take enough credits that would allow me to switch over to the Romance languages department.”

Happily, the professor who was teaching the Dante courses—Lino Pertile, who would later be a dedicatee for The Dante Club—had an idea that would provide the perfect solution. “Lino told me about the Longfellow House over on Brattle Street, and how the poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow had been the first American to do a complete translation of Dante into English, and that he did it there after the tragic death of his wife with the help of a support group that included Oliver Wendell Holmes and James Russell Lowell.”

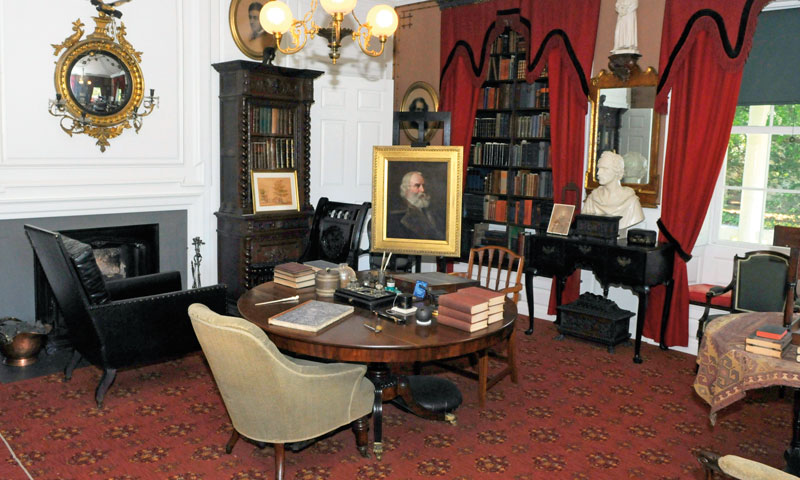

First known as the Wednesday Club by its members for the nights they gathered in the home of the iconic New England poet in the mid-1860s, the Dante Club, as it was later known, was, indeed, instrumental in providing insights and opinions during his translation of the monumental Italian epic, which appeared in 1867, and is still regarded by many critics as one of the very best in English. Especially significant, for Pearl’s purposes, is that the Longfellow House is now a National Park Service Historic Site, with furniture, artifacts, artworks, and archives maintained in situ by a professional curatorial staff that is only too happy to assist scholars, as I have learned over the past three years of my own research on Longfellow.

Just as important were the massive collections of Longfellow’s manuscripts, journals, letters, and lecture notes held in the Houghton Library at Harvard. Pearl’s thesis, “The Dante Club: A Re-assessment of the Emergence of Dante in Nineteenth Century America,” went on to win the college’s Thomas Temple Hoopes Prize for outstanding achievement in 1997, which came with a $2,500 cash award. “The idea that you could actually make money for something you wrote made a huge impression on me,” said Pearl, now a full-time Cambridge resident. “One of the reasons I continued to be interested in Longfellow and his group and the other writers I have written about since then is that I was, and still am, trying to figure out what it means to be a writer.”

Published in 2003, The Dante Club has, at its center, a series of murders being committed in 1865 in Boston and Cambridge by someone with an intimate knowledge of the grisly punishments meted out in the Inferno; a trio of amateur sleuths—Longfellow, Holmes, and Lowell—help solve the crimes. The novel’s stunning success led to four subsequent works; the most recent, The Last Bookaneer (Penguin, 2015), features an antiquarian bookseller.

Next up for Pearl is a mystery thriller, to be titled The Dante Chamber. “It’s a sequel, through Purgatory,” he acknowledged. “In a way it feels like it might be my last one in that world, although it just might not, either, because obviously there is still Paradise out there. But this is a continuation, in London, and still nineteenth century, sort of the British version of The Dante Club—with Christina Rossetti, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Robert Browning, Tennyson—who were all Dante lovers in their own lives.” All of which seems perfectly appropriate, given Pearl’s assessment of his own authorial beginnings. “For me,” he summarized, “it all went through Dante.”