A River Runs Through It

How Benjamin Franklin and his cousin, the Nantucket sea captain Timothy Folger, mapped the mighty Gulf Stream By Jeffrey S. Murray Jeffrey R. Murray is a former senior archivist with Library and Archives Canada, Ottawa, Canada.

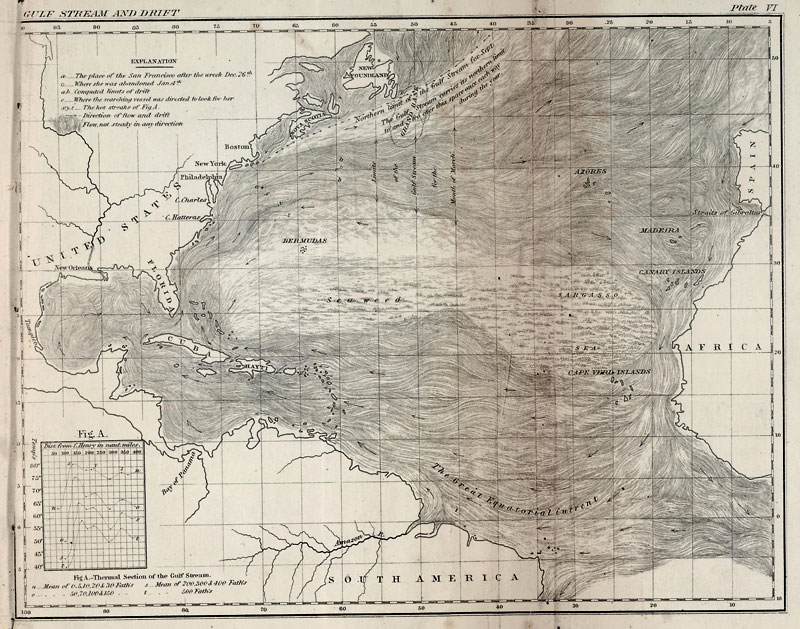

“There is a river in the ocean,” announced Matthew Fontaine Maury to the first congress of the National Institute for the Advancement of Science. As the officer in charge of the US Navy’s Depot of Charts and Instruments, Maury had been invited to the April 1844 meeting to discuss his latest research on the Gulf Stream, one of the least understood of the world’s ocean currents. Comparing this fascinating body of water to a land-based river was a little unusual, but as it turned out, quite appropriate since the Gulf Stream is almost as regular in its course as the Mississippi. As the current moves through its liquid channel at a rate of about one billion gallons a second, it remains unmixed with the confining waters of the Atlantic. But unlike land-based rivers, “in the severest droughts it never fails,” Maury later explained in his internationally acclaimed Physical Geography of the Sea, “and in the mightiest floods it never overflows.”

Although it was known since the days of the Spanish conquistadors, the “North-East Current,” as it was originally called, was not described in print until 1735 when Walter Haxton, an English tobacco merchant, included information on it in his chart of Chesapeake Bay. “It is generally known by those who trade to the northern parts of America,” wrote Haxton in an appendix to the chart, “that the current … runs constantly along the coast of Carolina and Virginia … Knowledge of its Limits, Course and Strength may be useful to those who have occasion to sail in it.”

But since there were no charts warning mariners of the boundaries or velocity of the current, it is little wonder that sea captains got caught in its powerful grip, needlessly adding an uncomfortable number of days and weeks to a transatlantic crossing. However, it was not until the 1760s that the Gulf Stream’s effect on shipping began to emerge as a matter of critical importance. New England merchants had noticed that mail packets bound for New York from Falmouth, England, consistently took two weeks longer to make the crossing than those traveling from London to Rhode Island. Considering there was only a day’s run between the two American seaports, the discrepancy needed an explanation. The Lords of the Treasury referred the matter to Benjamin Franklin, who was in London serving as the Deputy Postmaster-General for the American colonies.

Franklin, in turn, sought the advice of his cousin Timothy Folger. Described as “a very Intelligent Mariner,” Folger captained one of nearly 150 vessels that were employed in the Nantucket whale fishery, nearly half of which hunted along the margins of the Gulf Stream where the whales fed. Experience had taught the New England whalers not to wander into the current, lest the ship soon become separated from its prey. Even if it had a favorable wind, a whaler could expect to lose as much as seventy miles a day against the three-mile-an-hour Gulf Stream. Folger further explained that it was not unusual to find English sailors stuck in the current, and when they were advised “to cross it and get out of it,” the stubborn English sailors “were too wise to be counseled by simple American fisherman.”

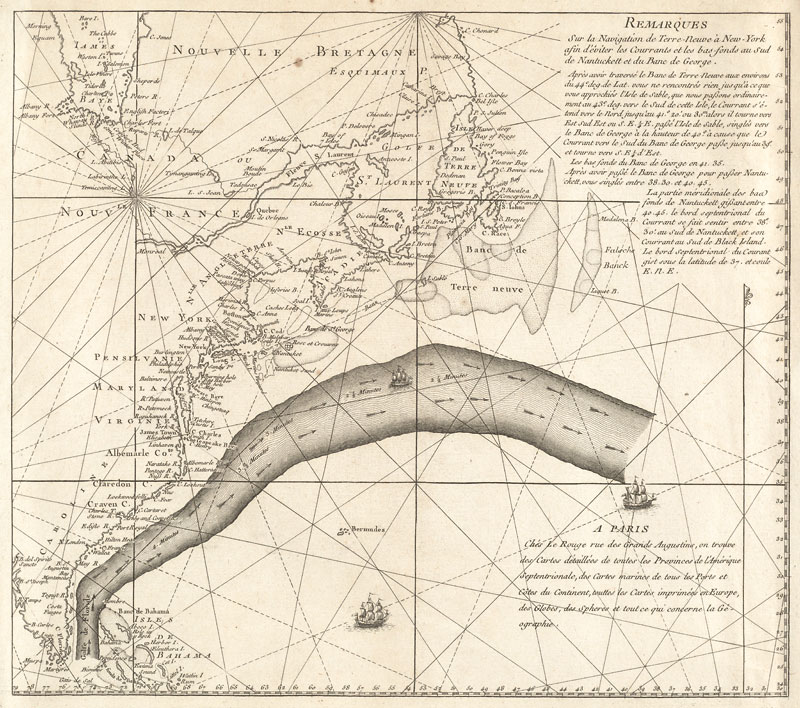

If shipping times were to be improved, British sailors needed nautical charts that accurately identified the course, breadth, strength, and extent of this unusual sea-born river. To this end, Franklin acquired copies of a four-sheet nautical chart of the Atlantic that had been published nearly fifty years earlier by John Mount and Thomas Page, “at The Postern on Great Tower Hill London.” Then with help from the post office, he had Folger’s sketch of the current engraved and superimposed on the older map, along with “some Written directions whereby Ships bound from the Banks of Newfoundland to New York may avoid the said Stream, and yet be free of danger from the Banks and Shoals.”

Copies of the republished map were sent to Falmouth for the use of the British mail packets. Unfortunately, few of their number showed any interest in it, which Franklin quickly dismissed as characteristic of the legendary conservatism of seamen. “Some sailors may think the writer has given himself unnecessary trouble in pretending to advise them,” wrote Franklin to a French colleague, “they have a little repugnance to the advice of landmen, whom they esteem ignorant and incapable of giving any worth notice.”

Despite Franklin’s claims to the contrary, British sailors actually had good reason to avoid his chart. To begin with, the geographical content featured on the Mount and Page base map was outdated. In the fifty years that had lapsed since it was first published, American coastline mapping had become considerably less fanciful and more in keeping with reality. Their crude outline of Newfoundland, for example, more closely resembled something from a century earlier than what competent cartographers were capable of producing in the 1770s.

As well, Mount and Page had situated their prime meridian at Lizard Point on the south coast of Cornwall near Falmouth. The peninsula is the last bit of Britain mariners see when setting out on a transatlantic voyage. But by the 1770s most English chart makers had informally accepted Greenwich as their prime meridian. In other words, longitudes on the Franklin-Folger chart were shifted 5°12' 8" to the west (or about 360 miles when measured at the equator) making it next to impossible to use the chart in conjunction with other navigational aids.

There was also a problem with the depiction of the Gulf Stream itself. Folger stopped the current in the mid-Atlantic at approximately 46° west of Lizard Point, near where the Stream forks into two branches. One part continues across the top of the British Isles and Norway, the other turns south and passes the Portuguese coast on its way to equatorial waters off Africa. Presumably the eastern end was unknown to Folger, which is not surprising since he normally sailed American coastal waters.

With the Revolutionary War on the horizon, Franklin seems to have backtracked on his attempts to reform British sea captains, and may have repossessed what few copies of his chart were circulating in order to keep them out of the British Navy’s hands (which would help to explain why only three copies are known today). However, following the war, he had two new editions of the chart printed. Other than the obvious size difference, the newer editions were more or less identical to his first attempt. One was translated into French and printed in 1785 by Georges-Louis Le Rouge of Paris; the other was published a year later in the journal of the American Philosophical Society.

While the latter was widely known in America’s scientific community, probably few mariners saw it. After his first contact with the mail packets, Franklin seems to have made no further attempts to communicate his findings directly to sea captains. Noting this discrepancy, the American historian Josef W. Konvitz has concluded that the Franklin-Folger chart contributed more to early oceanography than to seamanship.

One oceanographer that it is known to have influenced was none other than Matthew Fontaine Maury. In his Physical Geography of the Sea, Maury became the first to note the Gulf Stream’s complete circulation around the Atlantic, and effectively drew to a close the project Franklin had initiated eighty-seven years earlier. In doing so, Maury credited Franklin for his mapping ingenuity, noting his course for the Gulf Stream “has been retained and quoted on the charts for navigation … until the present day [i.e., 1855].” The Franklin-Folger chart was indeed a uniquely wonderful contribution to ocean science.