The Lost Libraries of London

A distinctive walking tour through one of the world’s great book towns focuses on historic collections dispersed by auction, war, and fire By A. N. Devers A. N. Devers is a writer, editor, and rare bookseller who lives in London. Her first book, Train, is forthcoming from Bloomsbury in 2018.

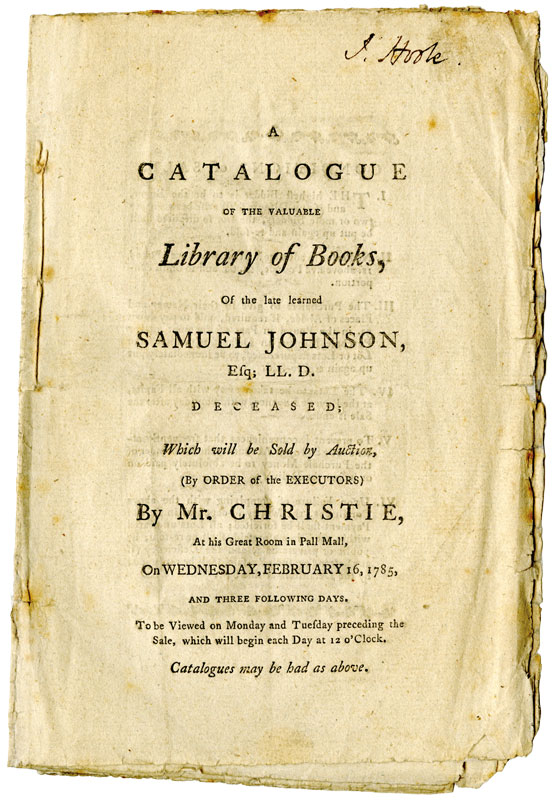

On February 16, 1785, three months after Dr. Samuel Johnson died, James Christie, the founder of Christie’s auction house, held a historic four-day auction of approximately three thousand volumes belonging to the Dictionary of the English Language author’s library.

Christie had been auctioning books for fifteen years, but selling the preeminent critic a language expert’s collection was a career-defining feather in his cap. Unfortunately for scholars, the catalogue produced for the sale is considered an example of what should not be done with a book auction catalogue, with many entries lacking proper titles, keeping scholars at a distance from what is arguably a keystone collection for studying the history of the English language and its origins.

At a fifteenth-anniversary Johnson Club dinner in Oxford celebrating Johnson’s work, the nineteenth-century clergyman and scholar, A. W. Hutton, handed out facsimiles of Christie’s catalogue while commenting on its poor quality, “ … when we turn to the catalogue itself, it is but a very sorry production, sadly unworthy of the occasion that called it into existence.” For example, there were thirty-six total grammar books, or “grammars,” listed, but that is all that is known about them, so academics must do text comparisons between the dictionary and possible book titles to piece together the gaps. Still, the catalogue gives scholars and collectors a general idea of what Johnson had at his fingertips while working on the dictionary. There were sermons, classical literature, philosophy, medical books, poetry and drama, and more. He had Milton’s Paradise Lost and plenty of copies of his own books.

“The whole amount realized was £242 9s,” Hutton reported of the auction total, “being at an average of about nineteen pence a volume, a truly lamentable result, considering that the library included many valuable editions of the classics printed in the sixteenth century, and the first folio edition of Shakespeare, which, if in good condition, as it probably was not, ought to have fetched more than the whole library went for.”

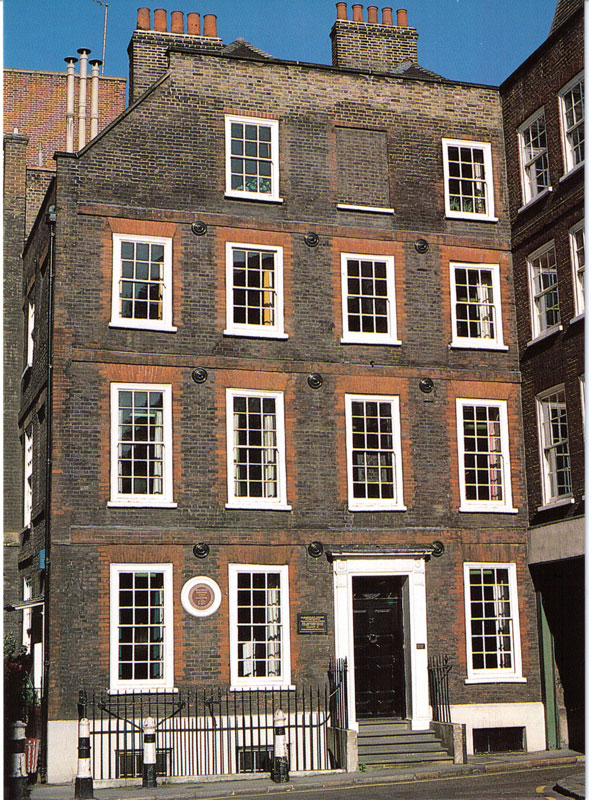

Hutton was wrong about Johnson’s Shakespeare—it was a second edition—but he was right to be offended by the result of the auction. In hindsight, the enormous import of Johnson’s library as formative to the first English dictionary is immeasurable, and it would have been beneficial and prudent to keep it together. Since its dispersal, Johnson’s books have been highly sought after and commanded high prices, despite being, as Hutton suggested of his apocryphal Shakespeare, in poor condition. Luckily for Johnson collectors, this also makes them identifiable—he annotated heavily and signed his name in most of them, as I first learned from Alice Ford-Smith, while standing outside Dr. Johnson’s House, on her walking tour of London’s “Lost Libraries.”