Collecting the Clippings

A happening market for hair collectors By Martha Steger Martha Steger is a freelance writer based in Midlothian, Virginia.

Hair collectors rarely have a bad-hair day—or so it seems in talking to Heritage Auctions’ consignment director Marsha Dixey. “On a good day, you can make $2,500,” from celebrity curls, she said, “but it all depends on many things—condition and size of the lock or number of strands, the market demand for a specific person’s hair, and, of course, the certificate of authenticity.”

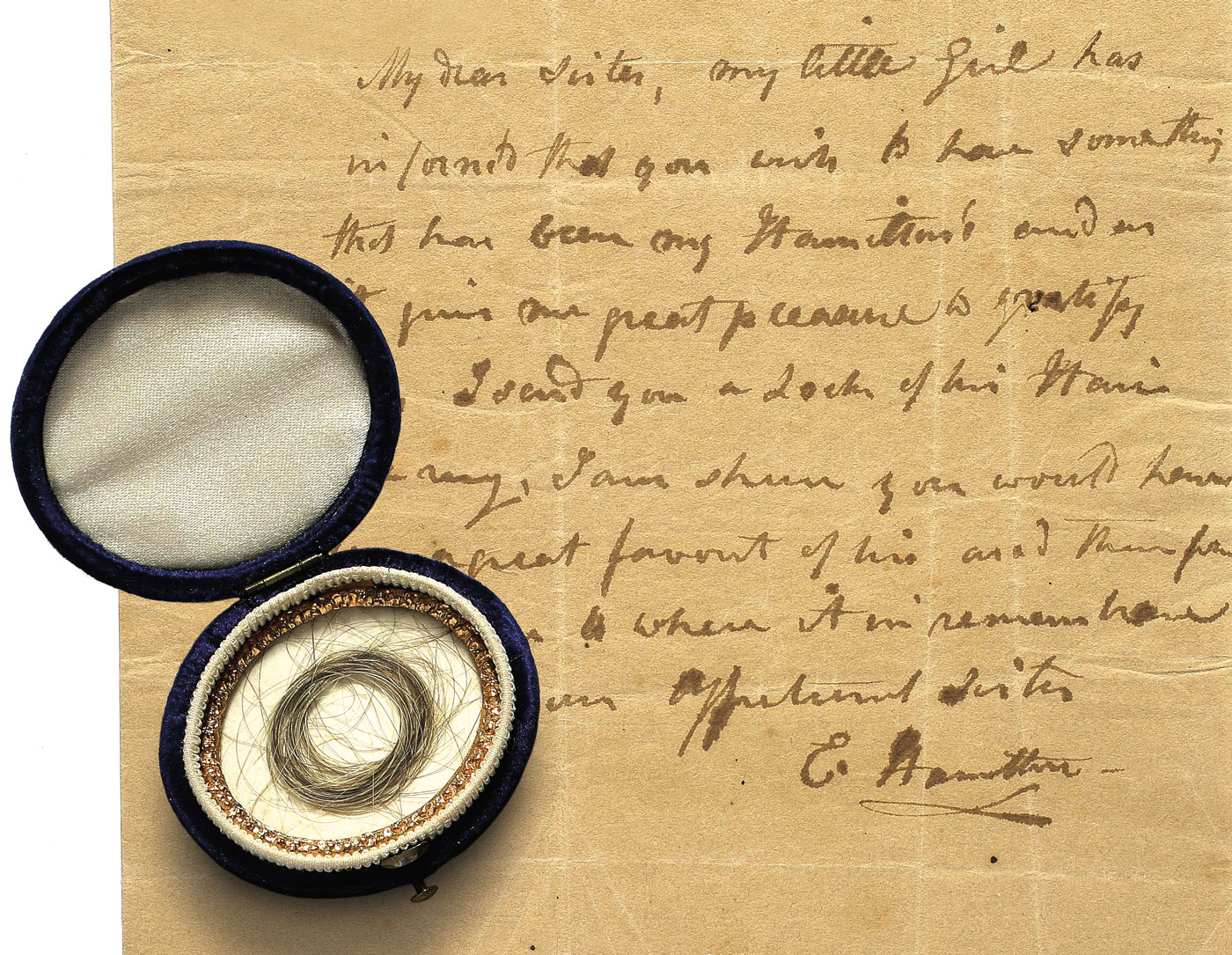

Political figures and pop idols do well. Heritage Auctions sold George and Martha Washington’s tresses entwined in a ca. 1800 brooch for $25,000 in May of 2017, yet a cutting from George alone brought $32,500 the previous December. Higher still was the price paid last year at Sotheby’s for a coil of Alexander Hamilton’s mane: $37,500 (though it was accompanied by a letter from his wife).

But hair collectors who know their subject and watch auctions closely can pick up a piece of history for much less. The Connecticut-based John Reznikoff, owner of University Archives, purveyor of historical documents and artifacts, did just that last October when he purchased what Dixey called “a substantial lock” from France’s Charles X for a mere $1,031. The lock’s provenance was good: an accompanying note, written in French and identifying the hair, bears the House of Bourbon’s coat of arms—historically significant because Charles X was the last French king from a main branch of the House of Bourbon.

“Short of a DNA test, any relic by its nature requires a leap of faith,” said Reznikoff, who most experts in the field regard as the world’s top hair collector. “The leap might be the size of a crack in the sidewalk or the Grand Canyon—but I try to make sure my leaps are cracks in the sidewalk.”

Reznikoff, who has been collecting hair for more than two decades, doesn’t purchase hair of living people. He said he doesn’t want to encourage stalking with scissors. He rarely sells any of the hair in his collection, which includes that of Kurt Cobain, Jimmy Hendrix, Edgar Allan Poe and wife Virginia Clemm, as well as presidents Eisenhower, Reagan, Nixon, and Kennedy.

Though some observers have an “ick” reaction to hair displayed from famous dead people, Reznikoff said, “I’m able to disarm every one of them by saying, ‘I bet your mother has a lock of your hair.’ A couple hundred years ago you valued a lock as a living token of affection—or when a friend or relative died, you clipped a lock as part of your mourning and remembrance.”

“Everyone loves a compelling story,” said Dixey, who doesn’t see the collectibles market for hair deflating any time soon. “That’s usually key, coupled with how much is there (four strands or a hunk?), plus the provenance—where it was obtained.” Like the snippet from Elvis, collected by his barber over a period of more than two decades from towels used around the singer’s neck, which sold for $16,730 back in 2010. Or a piece of John Lennon’s mop-top that was trimmed off when he was preparing for the 1967 film, How I Won the War, which made $35,000 at a 2016 Heritage auction. Or this perfect-storm example: a tuft of Che Guevara’s dark hair, which sold for $119,500 in 2007 to Texas bookstore owner Bill Butler. The hair was consigned by a C.I.A. agent who had supervised the Cuban revolutionary’s burial.