Tom Wolfe

Prior to Mr. Wolfe’s death on May 14, 2018, we talked to the bestselling author about politics, prose, and the death of New Journalism fifty years after The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test By Martha Steger Freelance writer Martha Steger, based in Midlothian, Virginia, interviewed Tom Wolfe after The Right Stuff came out in 1979 and again after his narrative on modern architecture, From Bauhaus to Our House, was published in 1981.

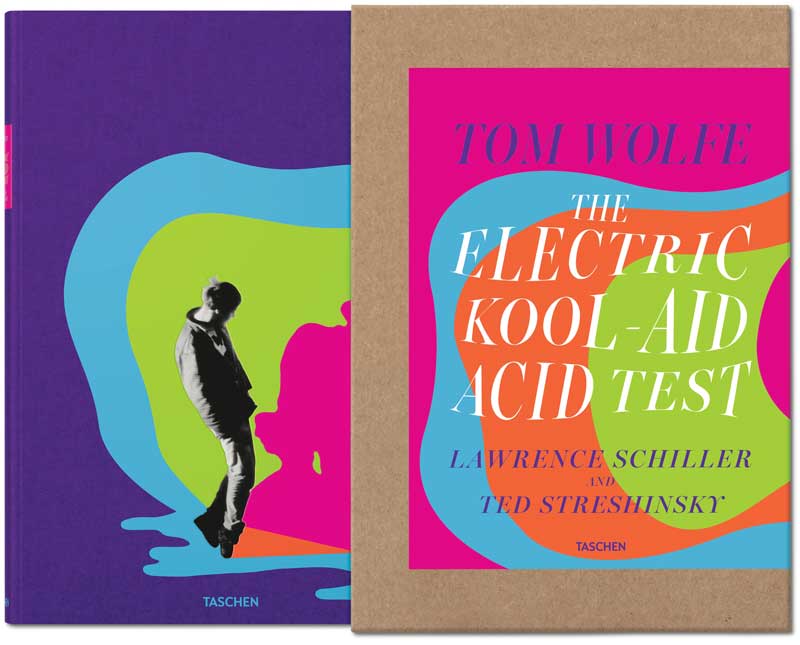

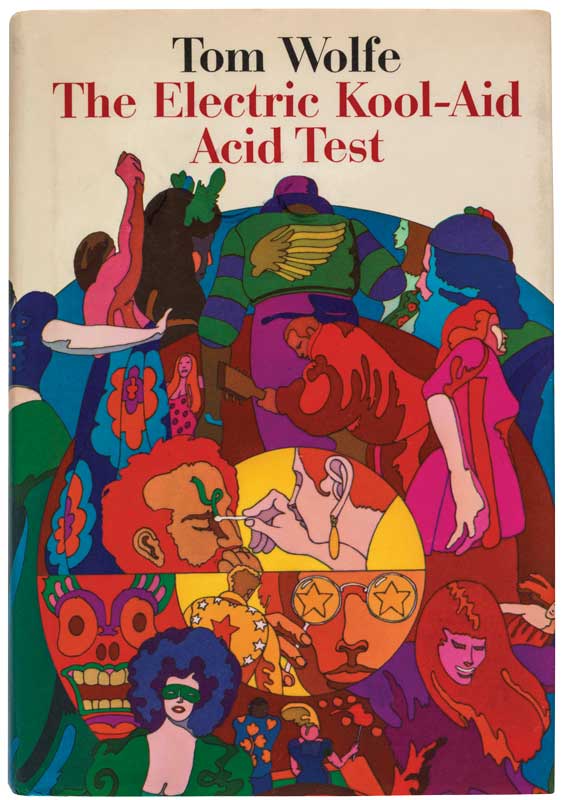

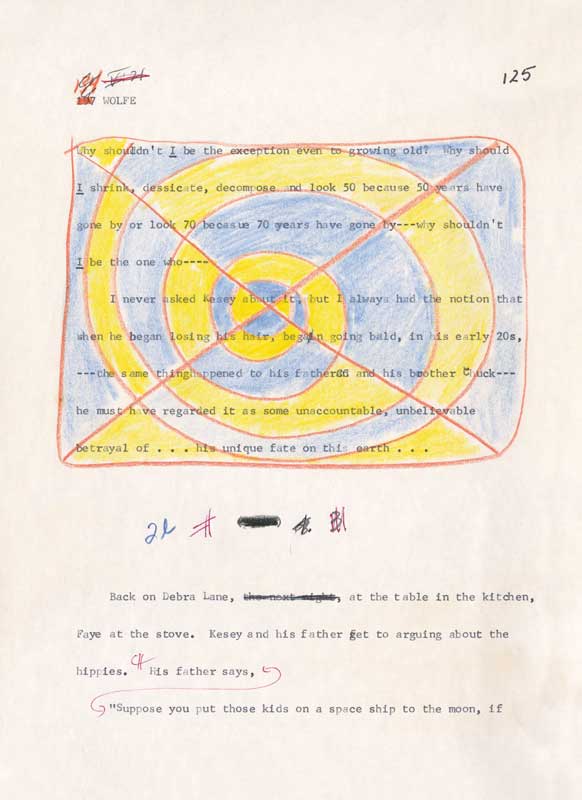

It’s not every bestselling author who lives to see collectors’ editions of his books, but Tom Wolfe is rare by many standards. This year marks the fiftieth anniversary of his countercultural classic, The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test, chronicling a LSD-powered cross-country bus trip by Ken Kesey and his Merry Pranksters, for which the German art book publisher Taschen had already put in place a letterpress-printed limited edition. Next year, the fortieth anniversary of his 1979 bestseller, The Right Stuff, is apt to see the same treatment, plus a National Geographic series. The author of several bestsellers, including The Bonfire of the Vanities and A Man in Full, Wolfe is, at 88, not content to rest on his laurels. Instead, he continues to chase the story.

In fact, Virginia’s native son is at work researching his next book. It will focus on the medical profession, though he isn’t sure whether it will be fiction or nonfiction. (A reader can’t help but wonder what he’ll come up with, especially given his prescient 1996 article, “Sorry, But Your Soul Just Died,” on neuroscience and brain imaging.)

Wolfe owes his success to breaking the conventions of traditional newspaper writing while remaining true to realism. Long before the advent of “trending,” Wolfe foresaw—and in some cases facilitated—American cultural trends. He predicted the rise of NASCAR with his March 1965 profile of Junior Johnson for Esquire magazine. “The Last American Hero Is Junior Johnson. Yes!” was the basis for the 1973 sports-drama film with Jeff Bridges as Junior Jackson, the character based on Johnson, who went on to win more than fifty races and become a team owner.

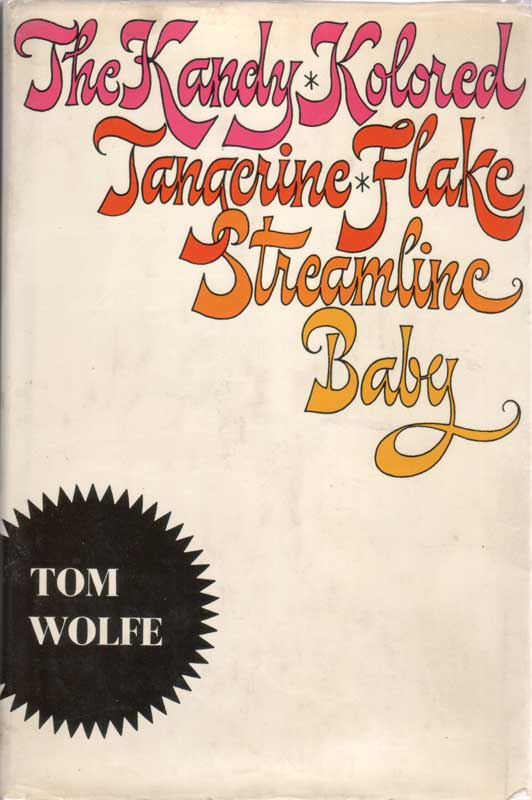

After earning a PhD at Yale, Wolfe’s career began in 1959 with a three-year stint as a city reporter for the Washington Post. In fewer than three years, he had moved on to the New York Herald Tribune. In 1962, when he was writing for New York magazine, he covered Southern California’s hot-rod custom car culture; the popularity of his 1963 article, “There Goes (Varoom! Varoom!) That Kandy Kolored (Thphhhhhh!) Tangerine-Flake Streamline Baby…,” gave rise to his first book, The Kandy-Kolored Tangerine-Flake Streamline Baby (1965), and must have stimulated his later curiosity about Junior Johnson’s early days of racing in North Carolina.

Although usually associated with the New Journalism movement, Wolfe has always been the first to say—as far back as 1972 in writing for Esquire—that he didn’t invent the idea or the term. If he didn’t invent New Journalism, Wolfe helped define it through his astute observations, immersion techniques, and innovative wordsmithery, e.g., lumpenprole: “a bunch of slick-magazine and Sunday-supplement writers with no literary credentials whatsoever in most cases—only they’re using all the techniques of the novelists, even the most sophisticated ones—and on top of that they’re helping themselves to the insights of the men of letters while they’re at it—and at the same time they’re still doing their low-life legwork, their ‘digging,’ their hustling… .”

Most often publicly seen striking a sharp pose in a top hat and one of his three white suits (the fourth is being cut by a new tailor, he said), Wolfe is in no way flashy or dramatic in a conversational setting. His contrasting demeanor in speaking engagements over the years has demonstrated his talent for timing and tone, honed during his fifty-plus years as a writer.

This past January, I visited Wolfe in the book-and-art-filled apartment he shares with his wife on Manhattan’s Upper East Side to talk about books past, present, and future.

Steger/ You said in the late 1970s that people frequently confused you with North Carolina’s Thomas Wolfe. At that time, you said you often got his mail and you wrote each fan back, ‘Unfortunately I’ve been deceased a number of years.’ Do you still get confused with that Thomas Wolfe?

Wolfe/ That’s no longer a live issue. Sadly, Thomas Wolfe is not read avidly any longer.

Steger/ You’ve also said in the past that you didn’t invent New Journalism. Who did?

Wolfe/ Pete Hamill was the first to use the term, I think. Seymour Krim [New York writer and literary critic] said Hamill asked him, ‘Why don’t we do a piece on this new journalism?’ I don’t think the article ever ran, but Hamill began using the phrase, and it stuck.

Steger/ New Journalism involved delving deep into a subject. You were avidly read early on because you embedded yourself inside diverse cultures and groups. How do you set up those relationships?

Wolfe/ I never say, ‘I want a lot of your time.’ I’ve always started with one person and if I could get along with that one person, I would just follow the chain of associates. If you can get through a whole day with a person, then it will work out fairly easily. People have different techniques for entering [subjects]. Jimmy Breslin, my colleague at the New York Herald Tribune, was really aggressive. George Plimpton was not very aggressive. He would do things like play first base with the New York Yankees and that sort of stuff. That had to be set up ahead of time, but he never went charging out on the basketball court saying, ‘Well, okay, what shall I do?’ He would hang around near the wall until someone said, ‘George, come out.’ That was another way [of entering a subject]. I just go with the natural approach. I worked on the Herald Tribune where we would be sent out to do man-on-the-street interviews. I found there was no use saying, ‘Hello, I’m with the New York Herald Tribune and we’re doing a street survey…’ You had to start off with your notebook and saying, ‘Here’s our question today.’ You have to adapt yourself.