A Quest for Illumination

The earliest known Hebrew Torahs in codex form date from the tenth century and were made in the Middle East and Northeast Africa. Only in the mid-thirteenth century do illuminated copies begin to appear in Northern Europe. By then, these manuscripts were serving the needs of wealthy members of the Ashkenazi Jewish community who had settled the areas along the Rhine around the end of the first millennium (now western Germany and northern France).

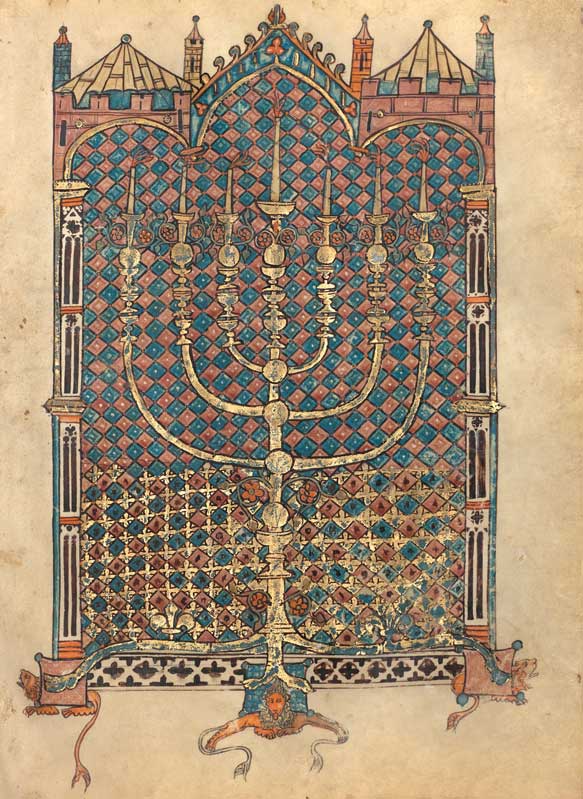

The Rothschild Pentateuch’s lavish illumination divides the text into sections to be read weekly so that the entire Torah would be read over the course of a year. The opening of each of the five books is celebrated with monumental Hebrew initials intertwined with lively marginal figures or a full-page illumination. Introducing the book of Leviticus is a commanding miniature of a shimmering menorah set against a geometric background of blue, rose, and gold. The towers that surmount the illumination evoke the setting of the tabernacle, the earthly dwelling place of God, where the menorah served as the only source of light. The miniature serves as an appropriate transition from Exodus to Leviticus, for Exodus details instructions for the building of the tabernacle while Leviticus documents the proper care of the tabernacle implements, including a pure gold menorah.

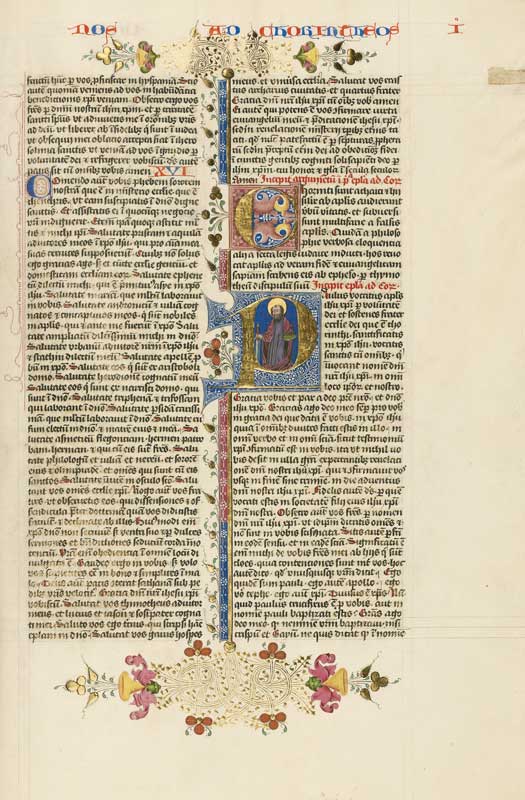

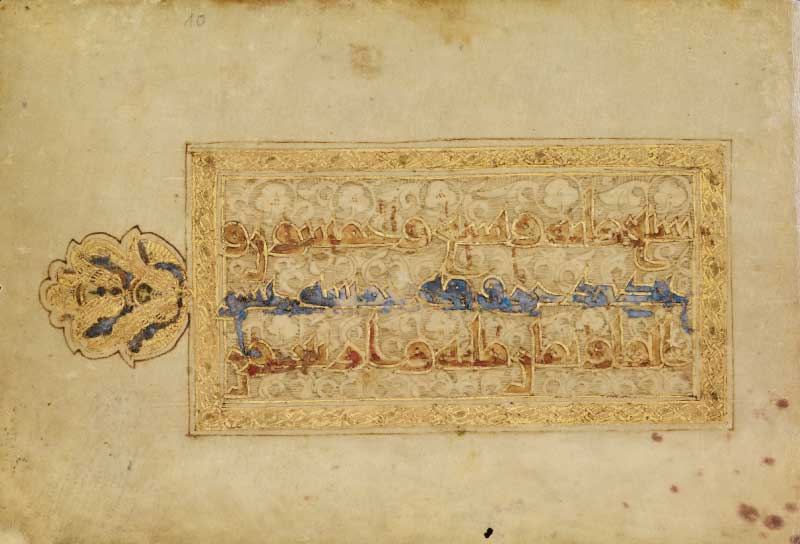

The acquisition of the Rothschild Pentateuch allows the Getty, for the first time, to represent the medieval art of illumination in the sacred texts of the three Abrahamic religions—Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, founded in that order. These religions trace their belief in the singular God to a common patriarch, the figure of Abraham (Ibrahim). Practitioners of all three religions have been called “people of the book” for their shared belief in the primacy of the divine word as conveyed through sacred scripture. Copies of the Torah, Christian Bible, and Qur’an are among the most beautifully illuminated manuscripts of the Middle Ages, represented by three objects from the Getty collection in Art of Three Faiths: a Torah, a Bible, and a Qur’an, on view until February 3, 2019. In addition to the Rothschild Pentateuch, visitors encounter a Christian Bible made in Cologne in about 1450, precisely during the years following Johannes Gutenberg’s introduction of the printing press in Central Europe. Throughout the book, we can observe centuries-old hallmarks of handmade books: carefully ruled lines (visible in the margins) arranged in two columns, embellished with decorated letters and pen flourishes. A ninth-century Qur’an from Tunisia complements the group. It was made within one hundred and fifty years of the prophet Muhammad’s death and is one of the earliest examples of chrysography (or writing in gold) of the period. Each of these manuscripts demonstrates that the word of God (Allah) provided luminous opportunities for artful decoration in book form.

The exhibition was organized by three of the curators in the manuscripts department, an unusually large team for an exhibition of just three objects. The plan to create a presentation that would allow us to represent the three major faiths of the western Middle Ages came about quite suddenly on the heels of the acquisition and required quick collaboration. Perhaps the biggest challenge was that the Pentateuch—and to some degree, the exhibition—had to remain a secret until the acquisition was officially announced. These circumstances meant that all of the usual exhibition design and communications meetings happened behind closed doors with a team that was sworn to secrecy. Now, we are delighted to be able to share this exhibition and our newest manuscript publically and enthusiastically.