Half-Baked Alaska

Did Sir Francis Drake Reach Alaska? Don’t Believe the Mapmakers.

By Derek Hayes

I recently heard a lecturer at a local museum argue that the intrepid Elizabethan explorer and buccaneer Sir Francis Drake landed in my local bay—Semiahmoo Bay, now bisected by the U.S.-Canada boundary between White Rock, British Columbia, and Blaine, Washington—in 1579. This was not the first such argument I had heard, though all the previous ones were for different locations, all held dear to their proponents’ hearts.

The issue with Sir Francis Drake is how far he made it north along the West Coast toward Alaska. There is plenty of evidence that he was on the West Coast and plundered a Spanish galleon off Central America. A number of maps depict his voyage of 1577–80, the first circumnavigation of the world by an Englishman, and the first in which the ship’s captain also made it around the world. (Magellan’s ship the Vittoria was the first circumnavigation, in 1519–22, but Magellan died in the Philippines and the ship arrived home captained by Juan Sebastián del Cano.) There seems little doubt that Drake sailed north looking for a western entrance to the Northwest Passage—and, laden with plunder, a quick way home.

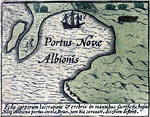

But Drake’s ship—first the Pelican and then the Golden Hind (one of the few that had its name changed while at sea, that usually being considered bad luck)—developed leaks and had to be beached for repairs. As was common in those days, the caulking between the boards of his wooden hull was beginning to fail. One map, an inset on a world map published by the Dutch mapmaker Joducus Hondius in 1595, depicts the harbor where Drake careened his ship—Portus Novæ Albionis, or Port of New England, the name he had bestowed on the entire west coast of America (see map 1).

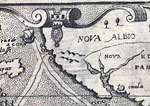

In addition to the inset map, Hondius’s world map shows the track of Drake’s ship apparently erased or altered halfway up the West Coast, a feature shown on a few other maps drawn at the time as well (map 2). And here lies the controversy. The theory is that Queen Elizabeth wanted to keep the Spanish spies at her court in the dark, to lead them to believe that Drake had indeed discovered the Northwest Passage (a belief that was reinforced by the fact that Drake, by pure luck, had had an unusually speedy passage back to England). Despite the fact that entire books have been written supporting the idea that he reached Alaskan waters, there is actually no hard evidence that defines how far north Drake reached, looking for the passage, before he gave up and decided to turn back.

The map of Drake’s harbor has spawned many theories as to its location. The best supported by the available evidence at this time is Drake’s Bay, on the south side of Point Reyes, just north of San Francisco. Others include San Francisco Bay itself; Whale Cove, on the Oregon Coast; and Boundary Bay and Semiahmoo Bay in British Columbia. All the theories have one thread in common: They equate a similarity between today’s coastline and that shown on the map as supporting the case for their location. Some of these are quite believable, with explanations available for almost every feature shown on the map—an island that could become a peninsula at high tide, for example.

The question is how far north Drake managed to sail in 1579.

But there are many inherent dangers in this approach. Mapmakers of the day were faced with many blanks on their maps, regions they had to fill to make their public believe they had something worth buying: new information. There are hundreds if not thousands of examples of maps where features, especially coastlines, have been drawn from imagination, only for later generations to find they actually look like those on a modern map. This is what makes these theories so attractive: Could such similarities be mere coincidence? But further documentary or archeological evidence is needed before we can equate the theory with fact.

One book—which is rumored, perhaps not coincidentally, to have made its author a great deal of money—claims that Drake reached Alaska. The author points to four islands shown on a map drawn by Nicola van Sype about 1583 (map 3), concluding that they represent Prince of Wales Island, in the Alaska Panhandle; the Queen Charlotte Islands (as one island); Vancouver Island; and Washington’s Olympic Peninsula, somehow perceived from the sea to be an island. The presence of these islands, the author argues, proves that Drake must have reached at least as far north as the Alaska Panhandle. However, the author failed to notice that these same islands, at exactly the same latitude, actually appeared on a world map published nearly 20 years earlier, in 1564, by the famous Dutch mapmaker Abraham Ortelius (map 4), and thus could not possibly have derived from Drake’s voyage in 1579. They are in fact merely a copy of one mapmaker’s work by another, something that happened all the time in the days before copyright.

Detailed examination of another piece of evidence advanced in this book led me to become even more skeptical. In trying to prove that the English twice altered a narrative account of the latitude reached by Drake, the author used the results of a “spectral analysis” carried out at his request by the British Library, where the document resides. But the author used only the evidence from the British Library report that suited his thesis; he omitted the report’s conclusion that all the changes had been made before the ink dried, hardly time for the series of nefarious staged alterations the author describes.

This is just one case—one where fortuitously I was able to actually document the process used to come up with conclusions. It underlines the necessity of viewing with a healthy skepticism any conclusion not clearly based on scientifically acceptable evidence. Historical hypothesizing can be great fun, but it should not be confused with proper research.

Derek Hayes is the author of a new book titled the Historical Atlas of the American West, which will be published by the University of California Press this fall.

Derek Hayes is the author of a new book titled the Historical Atlas of the American West, which will be published by the University of California Press this fall.