The Wright Stuff

Of Mice and Milton

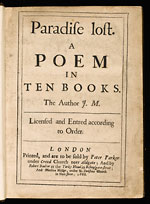

John Milton, Paradise Lost, £23,750 ($36,280) at Sotheby’s in London on July 15.

The title-page that you see here was long regarded as representing a third state of this famous work, but in a 1963 issue of The Book Collector, Hugh Amory questioned this view and most scholars now regard this 1668 title-page, employing Milton’s initials not his full name, as indicating the true first issue.

Amory located just seven copies with this form of title-page and this example, lacking the initial blank and showing some minor soiling and some darkening to the text in its modern Rivière binding of full crushed morocco gilt, adds to that number. Very few copies in period bindings are recorded but one of them is certainly worth noting here, even though it is twenty years since it last came to auction.

The Isham family library at Lamport Hall was unknown to the wider world until 1867, when Charles Edmonds of London booksellers Willis & Sotheran found the books “in a back lumber room … covered with dust and exposed to the depredations of mice, which had already digested the contents of some.”

Among those that had escaped the mice, Edmonds found hundreds of books of what he called trifling value (what price nowadays, I wonder?) and “a little collection of volumes … the very sight of which would be enough to warm the heart of the most cold-blooded bibliomaniac.”

One was an exceptional copy of Paradise Lost in contemporary calf, and just to make it even more appealing, a wooden case was made for it using part of a rafter removed from the London house in which Milton had started writing his great poem.

The travels of that superlative Isham Hall copy are well documented. Following its discovery, it was acquired by Wakefield Christie-Miller for his library at Britwell Court and there it remained until 1919, when it was sold at Sotheby’s for £460. Seven years later, Anderson Galleries of New York sold it for $10,000 as part of the library of Robert B. Adam of Buffalo, New York, and in 1935, sold it once more, this time from the collection of Seth Sprague Terry of New York. The buyer at $17,5000 was the now legendary US dealer, Dr. A. S. W. Rosenbach, but the book ended up in the English literature collections of one of his major clients, Arthur A. Houghton. When the Houghton library was sold at Christie’s in London in 1979-80, it went to Rosenbach’s former assistant and successor, John Fleming, at $41,800 and last surfaced at Sotheby’s New York in 1989, when as part of Haven O’More’s ‘Garden’ library, when it made $253,000. What might it fetch now?

Margaret the Black’s Lighter Side

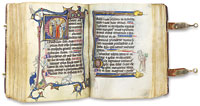

The “Psalter of Margaret the Black” (illuminated manuscript), £97,250 ($146,945) at Christie’s in London on July 7.

Part of the wonderful Arcana Collection, this charming little psalter, written and illuminated on vellum in Flanders in the last quarter of the thirteenth century, boasts a profusion of those little marginal drawings, or drolleries, that are so appealing to today’s collectors. It was probably made in Ghent or Bruges, and from the armorials that it bears and the fact that the only female saint depicted is St. Margaret, it is now known as the “Psalter of Margaret the Black.” Countess Margaret of Flanders was so-called not because of her color or temperament, but from the number of occasions that she was forced into mourning.

There is nothing dark or sad about the manuscript. The one hundred or more marginal drolleries or vignettes, the eight calendar miniatures, the large historiated initials with full borders populated by human, animal, and mythical figures, that decorate her little devotional text are a thing of joy and beauty.

On one page of the spread reproduced here, a huntsman and his dog have chased a hare up part of the frame of an historiated initial, while opposite is seen the figure of a monk. Others marginal drolleries include a hybrid fish-human balancing a spear on his chin, a dog standing on its hind legs to hold aloft a banner bearing the arms of Flanders; a woman holding holding a wreath of flowers that frames a natural hole in the vellum, and St. Francis preaching to two birds.

Ian McKay’s weekly column in Antiques Trade Gazette has been running for more than 30 years.

Ian McKay’s weekly column in Antiques Trade Gazette has been running for more than 30 years.