Wishful Thinking

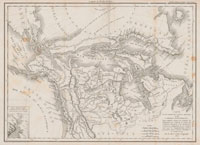

La Verendrye and his four sons spent the rest of their lives searching in vain for this magical route. Their quest eventually took them within sight of the Rocky Mountains. One would assume that failure to find the mysterious grand river of the west would have dispelled the rumors of its existence, but on the contrary. French cartographers simply relocated it to the other side of the Rockies. “It is precisely on the other side and at the foot of these mountains” argued Father Castel, a Jesuit missionary and scholar based in Paris.

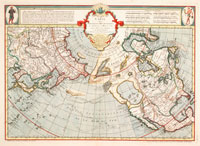

Another theory thought the passage would take the form of a great inland sea that connected the Pacific with Hudson Bay. Champlain himself was among the first to champion this idea. In one chance meeting he had with some natives while exploring the upper reaches of the Great Lakes, he heard of a great inland sea. “I hold that if this be so, it is some … sea which overflows in the north in the midst of our continent.” His mythical sea—which he labeled Ocean Glacial or Mer du Nort Gracialle—was thought to extend south and west of Hudson Bay, its icy waters covering much of what we now know as the Midwest.

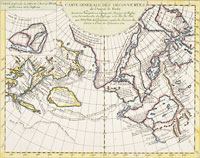

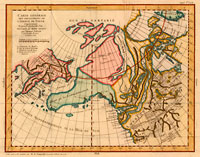

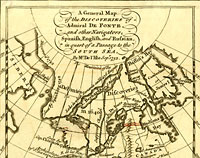

Perhaps the strangest and most imaginative maps showing a Northwest Passage were those based on the apocryphal 1640 voyage of the Spanish admiral Bartholemew de Fonte. In a letter published in a 1708 edition of the British magazine The Monthly Miscellany or Memoirs for the Curious, de Fonte claimed to have sailed up the Pacific coast of the Americas. Somewhere north of Vancouver Island he found a strait that led to a great inland sea where he met a merchant ship from Boston. Although it is now believed that the magazine’s editor wrote the piece, the great English proponent of the passage, Arthur Dobbs, took the article to be genuine and gave it credibility when he included the de Fonte expedition in his An account of the countries adjoining to Hudson’s Bay in the north-west part of America (1744).

The de Fonte ‘discovery’ remained a cartographic realty for more than half a century and entrapped some of the brightest and most prominent mapmakers, among them Joseph-Nicolas de L’Isle (a member of the French Academy of Sciences), Thomas Jefferys (the official Geographer to King George III and producer of a wide range of commercial maps), and Benjamin Franklin. In a thirteen-page letter to Sir John Pringle, King George III’s personal physician, Franklin weighed the evidence and concluded “De Fonte’s Voyage is genuine … & that the Country upon that Passage is for the most part habitable, & would produce all the Necessaries of Life.”

The Treaty of Paris (1763) left France without any significant possessions in North America and their interest in the western sea became purely academic. It was now up to the British to finish the search. In an effort to help advance the debate, Britain’s Parliament passed an act (first in 1745 and re-affirmed again in 1775) that offered £20,000 to the first ships of His Majesty’s Royal Navy to confirm its existence. Over the next quarter century, British interests approached the passage from its supposed eastern and western outlets.