Edward Curtis’ The North American Indian

He didn’t, what with his visits to eighty tribes, his forty thousand negatives, his countless interviews on manners and customs, his tribal histories, his recording of legends, myths and stories, his linguistic studies, his wax cylinder recordings of music, songs, and chants, the basic concepts of seventy-five different languages recorded, and over ten thousand songs recorded. He was the first person to make motion pictures of Native Americans. With his assistants in tow, he tried to record everything. “Curtis brought a real love and respect towards, and curiosity about, Native cultures,” noted Anne Makepeace, author of Edward S. Curtis, Coming to Light and director of the documentary on Curtis, Coming to Light. “He didn’t want to just capture their images … he wanted to enter their lives.”

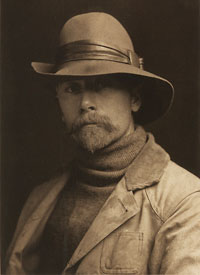

Curtis was born to a Civil War veteran and his wife in 1868 in Whitewater, Wisconsin. Having dropped out of school in the sixth grade in Minnesota, he was a mostly self-taught man. He made his first camera and was immediately smitten with it. So much so that by the age of seventeen, he was a photographer’s apprentice in St. Paul.

In 1887 the family moved west. For $150, Curtis, now in the bustling frontier town of Seattle, opened a photography shop of his own with Rasmus Rothi. Several months later he broke free from that and created another studio with Thomas Guptill. Curtis and Guptill Photographers and Photoengravers was a successful business. Wealthy Seattleites appreciated Curtis’ talent for portraits. He started to make a name for himself with his gold and silver photo processing called “Curt-tone.” He owned the photography studio outright by 1897, marrying Clara Phillips and beginning a family in the meantime.

His star rising, Curtis headed to nearby Mount Rainier one fateful day in 1898. He happened upon a lost climbing party. He guided them on the mountain himself and made fast friends with members of the party that included Clinton Hart Merriam, head of the U.S. Biological Survey, and George Bird Grinnell, editor of Field and Stream magazine. Soon, Curtis was invited to join them as official photographer of an expedition to Alaska sponsored by railroad magnate Edward Harriman. Curtis gladly accepted.

On that journey Curtis became acquainted with naturalist John Muir and writer John Burroughs. It was also during this expedition that Grinnell, an expert on the Plains Indians, showed Curtis that the Indians were a vanishing race, one that should be preserved in some form or other. The seed was planted. Curtis publicly vowed to create a complete record of the North American Indian. It would take him, he reckoned, five years.

Meanwhile, as Curtis’ interest in Indians grew, he entered a “Prettiest Children in America” photo contest conducted by Ladies Home Journal. He submitted a shot of Marie Fischer that caught the eye of President Theodore Roosevelt. Roosevelt invited Curtis to New York to take pictures of the Roosevelt family.

Roosevelt heard then of Curtis’ project and gave him his full support. (In fact, Roosevelt would later write the foreword for the first volume.) Emboldened now by his growing national reputation, his friendships with leaders, writers, and men of wealth and circumstance, Curtis took whatever opportunity he could to stoke his success. He exhibited nationally. He lectured. But he needed money. The project would not be cheap; it required a benefactor. Curtis had the temerity to approach J. P. Morgan himself.

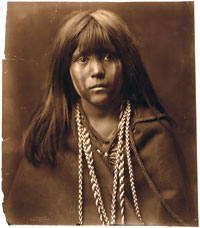

Morgan said no. The tycoon dismissed the photographer straight away at a meeting in Morgan’s lavish office. Crestfallen, and not having anything to lose, Curtis opened his portfolio for Morgan anyway. It was then that Morgan gazed upon the face of Mosa, a Mohave Indian child. Morgan’s assistant later claimed that it was only the third time that Morgan had ever changed his mind about anything. He agreed to give Curtis $15,000 a year ($75,000 in total) to create a twenty-volume set of ethnographic text with the highest quality photoengravings. And so the project began. The rest of Curtis’ life would be consumed by it.

He hoped to get five hundred subscribers to further subsidize the project. A deluxe edition (known now as “tissue sets”) would sell for $3,500 (a princely sum back then). The standard editions (either in Holland Van Gelder paper or on Japanese vellum) would sell for $3,000. He never got nearly that many subscriptions. Of the five hundred numbered sets that were planned, it remains unknown how many were actually printed. Only 272 copies were sold by subscription. That did not stop Curtis.