Ian McKay’s weekly column in Antiques Trade Gazette has been running for more than 30 years.

Ian McKay’s weekly column in Antiques Trade Gazette has been running for more than 30 years. Full Color

The Fibonacci Sequence

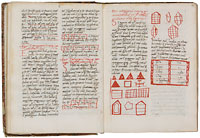

Fibonacci, manuscript copy of the Liber Flos, $338,000 at Bonhams New York on June 22.

The key part in a compendium of five medieval and older mathematical and astronomical treatises, all written in Italy in the late fourteenth/early fifteenth century, this rare manuscript comprises chapters fourteen and fifteen of the Liber Abaci by perhaps the greatest mathematician of the Middle Ages, Leonardo of Pisa, or Fibonacci.

A merchant’s son, born c. 1175, he learned the Arabic ways of arithmetic and computation whilst travelling in Europe and the Middle East as a young man, and in 1202, he wrote his first mathematical treatise, the Liber Abaci, or ‘Book of Calculations.’

No copy of this is known to have survived, but around 1228 Fibonacci completed a second version, to which was added the two chapters known as the Liber Flos.

The first section of the full work introduced to European readers for the first time the Indian numbering system and Hindu-Arabic numerals; the second dealt with mercantile calculations (introducing the use of zero and the idea that a negative number could be used to show a loss); the third and largest tackled mathematical problems, but it was the Liber Flos [Flower Book] that was the most mathematically advanced section.

Little is known of his later life, but his influence was felt for another five hundred years, and in 1500, Luca Pacioli acknowledged his complete dependence on Fibonacci in producing his own pioneering work, the Summa Arithmetica.

Of the few original manuscripts and contemporary copies, most are now in the Vatican collections. A dozen copies of the full Liber Abaci are thought to exist, and four separately transcribed examples of the Liber Flos. Two of those are in the Vatican library, and a third is in the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris.

The compendium containing this example was bound up for Prince Baldassare Boncompagni-Ludovici, an aristocratic nineteenth-century collector of mathematical texts and historian of science. It was he who first exposed Fibonacci’s work to a wider and modern mathematical community, though since the publication of The Da Vinci Code, millions more have at least come to hear the name via the Fibonacci sequence, in which each successive number is the sum of the two preceding numbers.

This example of the Liber Flos was last seen at auction in the 1970s. At that time it was part of the great Honeyman scientific library, sold over eight auctions and four years at Sotheby’s, and in 1979 it sold at £990 (then around $2,000) to the Amsterdam dealer Nico Israel. It was acquired from him by J. G. Bergart, and for the last thirty years has been on loan to the John Hay Library at Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island, who were doubtless sorry to see it go.

Grimm Beginnings, Fairy-Tale Ending

Jacob & Wilhelm Grimm, Kinder-und Haus-Märchen, $206,500 at Sotheby’s New York on June 17.

The work we now know as Grimms’ Fairy Tales was not originally envisaged as a children’s book, but was simply intended to document oral traditions and German folk tales about children. Philologists and folklorists, the brothers Grimm spent much of their lives working as librarians in the Ducal Library at Kassel, but in 1806 they began inviting storytellers to their home and writing down the tales they heard.

In 1812 they published their first collection of eighty-six German fairy tales as Children’s and Household Tales, following up two years later with a second volume of seventy tales. These were not dressed up for children, but presented in pedagogic fashion with faithful renditions of what they had heard, as the brothers viewed it primarily as an educational manual.

The awkward narrative style of many of the tales, some of which were repeated in several different versions, had limited appeal, and the horror and violence of some tales proved off-putting to others, and only a few copies of the original print run of nine hundred copies of the first volume were sold. Though more carefully edited, the second volume sold as poorly as the first, and it was not until 1819, when a second edition, rewritten and adapted for children, appeared that Grimms’ fairy tales found some happy endings.

First edition copies are thus extremely rare. There are very few in institutional collections, and the last auction appearance was in 1982.

The original volume in this set was a second issue of 1813, and both volumes showed some light browning and marginal spotting in rubbed and defective contemporary bindings of half calf over tan boards, but this was probably a once-in-a-lifetime chance to lay hands on a Grimm first.