| |

|

|

|

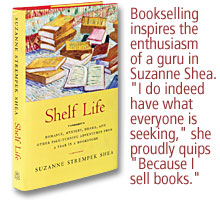

Shelf Life

By Suzanne Strempek Shea

Boston: Beacon Press, 2004

223 pages. $20.00

ISBN 0807072583

Books about books is a misnomer of a genre name.

If these titles were strictly about books, and nothing else, they

would be title catalogs threaded with wisps of narratives: “And

then I bought this. And then I sold that.” Such flat enumerations

would numb the soul of the most passionate bibliophile. The best

books about books are about books and people, specifically, about

the sellers, collectors, enthusiasts, and oddballs, including the

authors themselves. The people must be as interesting as the books.

Shelf Life is primarily about people, emphasizing the relationships

that a bookstore can foster among employees and customers, and even

bridging the canyon between sellers and buyers.

Shea is a writer whose previous book, Songs

from a Lead-Lined Room, described her diagnosis and treatment for

breast cancer. Following her recuperation, she took a job at Edwards

Bookstore in Springfield, Massachusetts, at the request

of friend and storeowner, Janet Edwards. Much to her surprise, the

author became an employee of a retail bookstore, stocking shelves,

filling back-orders, and arranging window displays. She captures

the mundane mechanics of selling new books, including the drudgery,

the frustrations, and the job’s greatest satisfactions—answering

questions and helping customers.

Edwards’s customers provide the book’s most humorous

and illuminating stories. A woman who needs a magazine article

calls the store and asks, “I don’t suppose you

could… cut out the article I want and mail it to me?”

A traveling businessman wants “something I’ll just read

and forget.” Shea considers creating a window display—Books

That Won’t Make You Think—but discreetly shelves the

notion. There are schoolchildren whose excitement about books is

not dampened by required reading lists and customers who would sooner

skip their morning cup of coffee than their regular shop visits.

An older gentleman, awkward and unsure, wants to know how to talk

with women or, more specifically, how to rekindle a romance

with one particular woman. “I’ve found the right one,”

he says. “I just don’t want to make a mistake.”

Any bookseller or librarian will recognize these characters.

These professions are kindred specialties. Both field questions

and decipher the wants of their patrons, finding the right book

for the right person on the right occasion. They wield empathy and

patience to understand what their customers need, especially when

their customers aren’t aware themselves what exactly they

want. It inspires the enthusiasm of a guru in Shea. “I

do indeed have what everyone is seeking,” she proudly quips.

“Because I sell books.”

Janet Edwards has run the store for nearly thirty years, and

her presence in the community is at once rock solid and catalytic.

“The customers call the store Janet’s because Janet

is the heart, the soul, the furnace from which emanates the warmth,

smarts, unflagging energy and goodwill that, despite the rather

hidden location, a ping-ponging economy, and big-box competition,

keeps the place alive.” Her coworkers (all of whom are women)

have a tight-knit symbiosis with the store. It’s not simply

a job for them, but a second family, providing close company, emotional

support, and potluck dinners. Janet correctly claims, “This

is a family business. We only hire family.”

Shea finds herself in the curious position of being an author

in a store selling authors’ wares, straddling several links

in the publishing food chain. She surreptitiously uses her position

arranging the store’s displays to promote her own titles at

the expense of big-name authors like John Grisham, who needs no

help moving volumes. When she recommends one of her books to a potential

buyer with a modest “I’ve heard it’s quite good,”

the woman responds, “Doesn't look it.”

There is another fascinating character at the center of

Shelf Life—the bookstore itself, a destination drawing people

of different backgrounds together to learn, exchange information,

and interact with each other. It’s a case study of the

bookstore in the ecology of a community. The story of Edwards Books

encompasses the story of Springfield, an industrial city in western

Massachusetts trying to revitalize itself after industry has abandoned

it. Stores like Edwards’s are institutions that form the DNA

of a good community, and like the strands of life, they are entwined

in its survival.

There are thousands of retail bookstores in the United States,

yet comparatively few are so special that they create a sense of

ownership in the community. Shea links the demise of

so many independents to the enormous inventories and influential

buying power of chain stores. “All the more reason,”

she suggests, “for traditional stores to stress ‘Let

me find that for you.’” Small, personal courtesies pay

off when customers tell her, “I could have gotten this online

for thirty percent off…but I wanted to do business here.”

That single statement may point to the major problem confronting

many independent bookstores today—and to a possible solution.

Shelf Life is a personal missive from the frontline of

the independent bookstore struggle. Shea warmly observes this world

and captures her colleagues’ and her own enthusiasm, but doesn’t

romanticize it. Bookselling, for all the magic bibliophiles find

in it, is also mundane, and Shea’s readers might see how difficult

and tiresome running a bookstore can be. Seasons and years pass,

children grow up and leave town, catastrophe strikes, wars come,

old friends pass on—but as of this review, Shea still works

at Edwards Books.

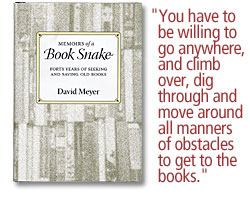

By David Meyer

Glenwood, Ill.: Waltham Street Press, 2001

152 pages. $23.00

ISBN: 0916638545

The malapropism “book snake” is applied

to David Meyer by an acquaintance reaching for the word “bookworm.”

“Snake” suggests a creature that navigates hazardous

terrain and tight corners in a single-minded pursuit of its prey.

“You have to be willing to go anywhere, and climb over, dig

through, and move around all manners of obstacles to get to the

books,” Meyer writes.

As a boy, he accompanied his father on weekly visits to

Chicago bookstores in the 1950s. The chapter, “The Bookmen

of My Youth,” remembers them, especially Bill Newman’s

Gallery Bookstore and the antiquarian department on the third floor

of Marshall Field, “when it was still the great department

store it had been for nearly a hundred years.” Meyer also

relates the fascinating story of Reinhold Pabel, a German soldier

interred stateside during the Second World War. Pabel escaped from

his prison camp, married, and opened the Chicago Book Mart before

he was caught by the FBI in 1953. He recounted his story in the

1955 book, Enemies Are Human. “If you bought ten dollars’

worth of books from Pabel,” Meyer remembers, “he offered

you a free copy.”

The book’s strongest chapter is a profile of Margaret

Donovan DuPriest. Meyer started his career as a “sometime

bookseller” at Maggie’s Old Book Shop in South Miami.

She’s truly a character: “As I dusted the books…I

read titles and checked contents with an idea toward purchasing

books for myself. Maggie frowned on this habit… She did not

consider me a customer, and it was the customers, not the help,

whom she was saving her books for. She may have also not liked the

idea of paying me, only to have the money handed back to her.”

On a whim, she later moved the store north to Greenwich Village

and rechristened it the DuPriest Book Shop, and then relocated it

a year later to Columbia, South Carolina, where she was disappointed

by a literary life less lively than that of New York. Maggie

would be a first-rate protagonist in her own story.

Meyer’s biography is filled with a similar wanderlust.

After college and military service in Vietnam, he traveled the country,

hunting for treasures in bookshops and uncommon places. Along the

way, he encounters remarkable titles, authors, and friends,

whom he often associates with a particular discovery.

Memoirs of a Book Snake almost falls

into the “And then I bought this” class of books about

books. Meyer likes to relate his great finds, bargains he later

resold for substantial sums, but the real highlights are the fascinating

people he meets. Meyer tells a good story and evocatively describes

several book people who should be remembered by collectors. The

chapters are brief, and so is the book itself, a small five-by-seven

inch volume. Unlike many self-published volumes, this is a little

book worth scouting.

Pasco Gasbarro |

|

|