| |

|

|

|

The Polysyllabic Spree

By Nick Hornby

San Francisco: San Francisco: Believer Books, 2004

143 pages. $14.00

ISBN 1932416242

Books are, let’s

face it, better than everything else,” writes Nick Hornby. If that

opening salvo doesn’t intrigue you as a bibliophile, or if you

strongly disagree with it, you should put down this magazine and find

something else worthwhile to do with your time (canasta, perhaps), because

everything that follows in Hornby’s book, and in this review, is a

passionate

and opinionated dispatch about reading books. To wit: “If we played cultural Fantasy Boxing League, and made books go

fifteen rounds in the ring against the best that any other art form had to

offer, then books would win pretty much every time.

Go on, try it. ‘The Magic Flute’ v. Middlemarch? Middlemarch in six. ‘The Last Supper’ v. Crime and Punishment? Fyodor on points.…Every now and then you’d get a shock, because that happens in sport, so Back to the Future III might land a lucky punch on Rabbit, Run; but I’m still backing literature twenty-nine times out of thirty.” Hornby is the author of several novels—High Fidelity, About a Boy, etc.—that

have been surprising critical and commercial successes;

because they’re good literature and they’re entertaining. The

Polysyllabic Spree is a collection of

Hornby’s monthly columns for The Believer magazine. Opaquely titled “Stuff I’ve Been

Reading,” every column begins with two lists: “Books

Bought” and “Books Read.” Sometimes there’s overlap

between them, but more often, there are curious differences and gaping

holes. Hornby spends much of the column describing what he read and

how he read it. He also makes excuses for what he didn’t read:

didn’t have time; something else came up; he read another book not on

the list; the book was unreadable or boring, and he just

couldn’t finish it.

The lists reflect the divergent interests and

wandering attention span of the average booklover. In one month, he read

Gustave Flaubert’s letters; John Buchan’s 1916 espionage tale, Greenmantle; Michael

Lewis’s Wall Street memoir, Liar’s

Poker; and a self-help book, How to Stop Smoking. In another month,

he completely focused on a single whopper of a book, Charles

Dickens’s David Copperfield. “Where would David

Copper-field be if Dickens had gone to writing

classes?” he asks. “Probably about seventy minor

characters short is where.” His observations on Dickens are

acute (“In The Old Curiosity Shop

I discovered that in the character of Dick Swiveller,

Dickens provided P. G. Wodehouse with pretty much the whole of his

oeuvre.”), as are his insights on literature, publishing, music, and

politics. He’s particularly poignant while discussing George

and Sam, by Charlotte

Moore,

a book about Moore’s autistic son. Hornby relates to the

book and the author because one of his sons is also autistic and, he says,

there are few books like Moore’s that really capture

the

experience of living with an autistic child.

Personal life and cultural life are tightly wrapped in

Hornby’s writing. He admits his peculiarities, ignorance, and

prejudices up front. He dismisses one book (the title and author shall

remain mercifully nameless here) based on single snippet of dialogue:

“I am positive that no one has ever said ‘Arsenal won Liverpool

3-0’ in the entire history of either Arsenal Football Club

or the

English Language.

‘Beat,’ ‘thrashed,’

‘did’ or ‘done,’ ‘trounced,’

‘thumped,’ ‘shat all over,’ ‘walloped,’

etc., yes; ‘won,’ emphatically, no.” Hornby’s first

book, Fever Pitch,

was about soccer, so he knows what he’s talking about here.

These aren’t remotely conventional book reviews.

Hornby’s columns are like a literary reality show in print: Man tries

to read all the books he buys and write a monthly column on deadline,

while striving to maintain a career, a family, and a semblance of

a social life. He doesn’t crack before our eyes, but he does get

physical while reading Wilkie Collins’s No

Name. “We fought, Wilkie Collins and I.

We fought bitterly and with all our might, to a standstill, over a

period of about three weeks, on trains and airplanes and by hotel swimming

pools. Sometimes—usually late at night, in bed—he could put me

out with a single paragraph.”

The process of reading a book is actually work, Hornby

reminds us, subject to short attention spans, forgetfulness, personal

crises, family business, and other interruptions from life. Besieged on all

sides by books— some outstanding, most mediocre —the

professional reviewer must read them all the way through out of obligation. The Polysyllabic Spree is dear to me, as Fine Books & Collections’s book review editor, because

I see my own dilemma in these pages. I don’t need pity, and

neither does Hornby.

But Hornby does sometimes ask for forgiveness,

something I’ve never seen a book reviewer do. “Last

month,” he writes, “I may have inadvertently given you the

impression that No Name by Wilkie Collins was a lost Victorian classic (the

misunderstanding may have arisen because of my loose use of the phrase,

‘lost Victorian classic’) and that everyone should rush out and

buy it. I had read over two hundred pages when I gave you my considered

verdict; in fact, the last four hundred and eighteen pages nearly killed

me, and I wish I were speaking figuratively.… I’m sorry for the

bum steer, and readers of this column insane enough to have run down to

their nearest bookstore as a result of my advice should write to The Believer, enclosing a

receipt, and we will refund your $14.

It has to say No Name on the receipt,

though, because we weren’t born yesterday, and we’re not

stumping up for your Patricia Cornwell novels.”

If his reviewing gig doesn’t work out, Hornby

can always rely on his other job as a novelist, but I hope he perseveres.

I don’t want him to crack before I do.

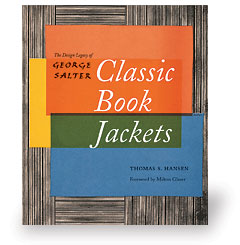

The Design Legacy of George Salter

By Thomas S. Hansen. Foreword by Milton Glaser. By Thomas S. Hansen. Foreword by Milton Glaser.

New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 2005

200 pages. $35 paper

ISBN: 156898491x

If you collect fiction

published in the United States during the middle years of the twentieth

century—by Thomas Mann, William Faulkner, Graham Greene, Ayn Rand,

William Styron, Franz Kafka, John Hersey, Hermann Hesse, John Dos Passos,

or quite literally hundreds of other lesser-known authors—you will be

familiar with the jacket art of George Salter. Salter (1897–1967) was

born in Germany and practiced design in Berlin until emigrating in 1934 to

the States, where he began designing books and jackets for American

publishers.

Trained in calligraphy and design, Salter was one of a

handful of designers, like W. A. Dwiggins, Jan Tschichold, and a few

others, who changed the look of American books from the 1920s to the 1960s.

Salter’s dramatic combinations of hand-drawn lettering and his own

imaginative renderings, based on his intuitive understanding

of the central idea or image of

a book, made for some of the most

distinctive book covers of the period.

Thomas Hansen, a professor of German

at Wellesley

College, has put together the first complete survey of Salter’s

life and work, and it’s both delightful to look through and a

concise, thorough, and semischolarly account of all of Salter’s work.

Hansen divides the short text portion (48 pages) into sections:

Salter’s “Berlin years,” his activities in the 1930s and 1940s

(“From Berlin to New York”), and a final section on his

“Designs of the 1950s and 1960s.” The bulk of the book is given

over to full-color reproductions of more than two hundred examples of

Salter’s best work. At the back of the book are appendixes listing

all of Salter’s designs for German publishers (1922–34) and

American book publishers (1934–67), as well as notes and an extensive

bibliography.

Hansen’s heroic dedication to filling in

the

gaps in Salter’s own records can be seen in the appendixes, where he

lists the nearly 1,000 commissions Salter completed for book jackets,

bindings, magazines, and record covers for an astounding array of clients

(about thirty-five in Germany and nearly a hundred in the U.S.), making

this something between a catalog raisonné and a comprehensive

bibliography.

|

|

|

|