FINE PRESSES

Janus Press

"When you work by hand," she said, "you have the luxury

of time that allows the materials to tell you what they want to be. Even

though I produce quite a bit of work, I wait for the work to be in a certain

form. I search for the right action, for the yes." For Van Vliet, what is

all-important in the work is its wholeness. "I don't think of myself as

a meticulous craftsman," she said. Here she spoke of others in her trade

who she would call masterful. In fact, she was consistently generous in

her praise of other fine presses during our talk. "I think of myself as

an orchestrator. I want all the things in a book to fall together. I want

all the parts to need to be there."

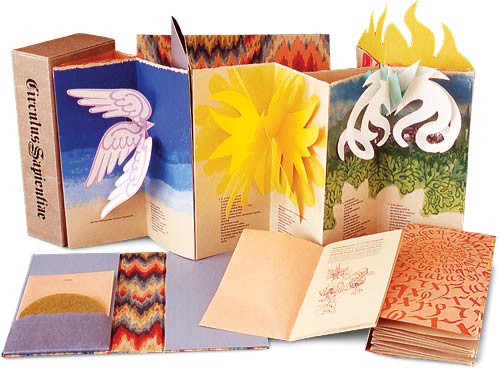

Circulus Sapientiea An elaborate construction

inspired by the medieval songs of Saint Hildegard. Published in 2001 in

an edition of 120 copies.

That means that there will always be a sense of

urgency to the work, an urgency derived from necessity that, as Ezra Pound

put it, makes art "news that stays news." And the proof is there: You can

open any book from the Janus Press, regardless of subject, regardless of

year, and feel this freshness and vitality.

Van Vliet has continued growing throughout her

long career. For example, in the late 1980s, she created the first of her "quilt" books,

Aunt Sallie's Lament, based on a poem by Margaret Kaufman. (It was later

produced in a trade edition by Chronicle Books.) There followed an inventive

series of books and broadsides inspired by the mostly anonymous American

quilt makers of the past. In 1989, she produced what Ruth Fine calls "the

most alluring of all the paperwork books," Dido and Aeneas. Fine also calls

it "the most complicated and… arguably the most ambitious of Van Vliet's

publications." This in Janus Press's thirty-fifth year.

These structural innovations-which she generously

reveals in Woven and Interlocking Book Structures, a book she co-wrote with

Elizabeth Steiner-may tend to overshadow the traditional work emanating

from Janus Press. That would be lamentable. In her 1976 rendition of Hayden

Carruth's poem "Loneliness," for instance, the reader feels what Neal Turtell,

the co-curator of the exhibit and the executive director of the National

Gallery Library, describes as Van Vliet's masterful employment of typography "to

be harmonious with the text." One of the things the curators hope this exhibit

will demonstrate is how the seeds for Van Vliet's accomplishments were there

from the beginning. Indeed, if you look carefully at the 1998 Janus Press

publication, Seven Poems by Emily Dickinson, created some twenty years after

the Carruth text, the link is inextricably there; the harmony is now unmistakably

clear and right and even more profound.

Still busy, still working hard, still ranging far

and wide, Van Vliet is presently finishing The Gospel of Mary, a text, according

to Fine, "thought to have been written at approximately the same time as

the better-known Gospels of Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John." Next up is The

Silences Between, poems by the New Zealand writer Keri Hulme, author of

the acclaimed novel The Bone People.

In speaking about the idea of making things deliberately

by hand, as she has done for fifty years, with the plentitude of time for

her artistic vision to reveal itself, Claire Van Vliet said, "That's why,

for example, there's such beauty in a handmade wall." Her fellow Vermonter

and maker of wonderful deliberate works of art himself, Robert Frost, couldn't

have described Van Vliet's vision better himself.