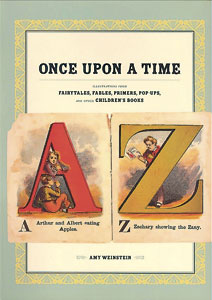

Illustrations

from Fairytales, Fables, Primers, Pop-Ups, and Other Children's Books

Illustrations

from Fairytales, Fables, Primers, Pop-Ups, and Other Children's Books The pop-ups and board books of today have their predecessors in the illustrated books of the mid to late 1800s—often called the golden age of children's literature. In the United States, the children's book market was dominated by McLoughlin Brothers of New York, publishers who used chromolithography, a newly affordable technology in the 1870s, to produce hundreds of titles in glorious color. These books entertained children while meeting parents' expectations of educational value. Once Upon a Time is a generously illustrated showcase of the notable collection of children's books (most from McLoughlin) assembled by Arthur and Ellen Liman and recently presented in an exhibition at the Museum of the City of New York.

The Liman collection includes, among others, ABC books, nursery rhymes, fairy tales, books shaped like theaters (complete with audiences in the wings), and—my favorite category—cautionary tales of the dreadful fates awaiting ill-behaved children. (You can't help but cheer on the urchin with her hat flying off as she skips rope with a defiant glare in Disorderly Girl, from the 1860s.) Amy Weinstein, a curator at the New-York Historical Society, discusses these books in the context of children's book publishing and changing ideas about childhood. Weinstein mixes a fan's appreciation of the books with tart reminders that children were marketing targets long before the advent of Saturday morning cartoons. "Get the story book!" read the promotional copy on a set of 1880s fairy-tale-themed wooden blocks, also produced by McLoughlin.

Perhaps the most intriguing books are the "moving picture" books of the 1890s and early 1900s, when film was attracting the public's attention. In The Motograph Moving Picture Book (London: Bliss, Sands and Co., 1898), the reader places a transparent, ribbed screen over the illustrations to create the illusion of movement in a fountain, a volcano, etc. McLoughlin's Story of the Firemen (1908/1911), with flames pouring out of a building and a horse-drawn engine racing to the rescue, is kin to the many Edison films on the same subject. Indeed, children's books, with their visual appeal and minimal text, may have provided models for those first motion pictures.

Once Upon a Time accomplishes just what the McLoughlin titles set out to do: educate and entertain. The beautifully reproduced illustrations are large enough to read the storybook text. (Dimensions of the books are not provided, unfortunately.) As I turned the pages, I could see the dog-eared, much-loved volumes of my own childhood. A child's physical relationship to the shape of a book is a simple pleasure—and surely, in every collector, that childish delight still lurks.