Projecting the Empire

In the years leading up to the Great Depression, the British government devised a sophisticated advertising campaign to boost trade across its Empire

By Jeffrey S. Murray Jeffrey Murray is a former senior archivist with Library and Archives Canada.

“Four years ago the Empire Marketing Board wasn’t in existence, now, you can go nowhere without being reminded of its influence,” wrote an unidentified female correspondent. She had found herself immersed in one of the most successful advertising campaigns to hit the streets of pre-depression era London. “Even if you are waiting for a bus,” continued her 1929 article in the Sydney Morning Herald, “you will probably find yourself standing beside a colourful poster … and by the time you have studied it … you have had a pleasant little lesson in Imperial matters, almost without knowing it.”

It was Empire Shopping Week, and shops throughout the city, from the smallest to the largest, had put together grand displays reminding everyone of the virtues of keeping their purchases within the British Empire. The campaign was the brainchild of the Empire Marketing Board (EMB) and was somewhat simplistic in its objectives: if British consumers bought agricultural produce from the Empire, the Empire would be able to use its increased purchasing power to buy manufactured goods from Britain. In the late 1920s, Britain was already feeling the pinch of an economic slowdown—a pinch that would eventually fester into the Great Depression of the 1930s. Anything that could stimulate trade between nations would surely translate into a win-win scenario for everyone.

“It is a great task,” admitted W. S. Crawford, vice chairman of the EMB’s publicity committee in The Empire Mail, “this rousing of the British peoples … to the realization of the importance of Empire. And the one force which can achieve it is that of advertising.” And advertise they did! With an annual budget of one million pounds (about fifty million dollars today), the EMB used every medium at its disposal to trumpet a message of Empire trade—from displays at agricultural shows to public lectures, films, colorful slide shows, billboards, and newspaper advertisements.

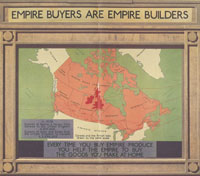

But, just as the unidentified correspondent to the Sydney Morning Herald had discovered, it was the EMB’s poster campaign that was the most memorable, and certainly the most prolific. Although they varied considerably in style, the posters universally romanticized hard work, bountiful fields, busy factories, and crowded shops. Maps were a favorite theme in the EMB’s poster arsenal, and one of its earliest poster designs was a map of the Empire and the ocean highways that linked it to Britain.

The EMB commissioned its Highways of Empire map from MacDonald Gill, a popular graphic artist who had already made a name for himself a few years earlier with a humorous map of the London subway system. His latest project featured an unusual spherical projection and a style that was vaguely reminiscent of renaissance cartography: stars fill the night sky, cherubs blow the major winds, ships ply the world’s oceans, and wildlife embellishes the periphery. Even Gill’s scrolled annotations and use of Latin are reflective of earlier mapping periods, but his bold use of color and strong curved lines definitely gave it a more contemporary Art Deco appeal. No doubt, Highways of Empire would have caused many passersby to hesitate a few moments and seriously contemplate “imperial matters” just as the Sydney Morning Herald correspondent had discovered.