Walk the Line

Two and a half centuries ago, Charles Mason and Jeremiah Dixon started their epic survey along what would become the most celebrated border in America Jeffrey S. Murray Jeffrey S. Murray is a former senior archivist with Library and Archives Canada.

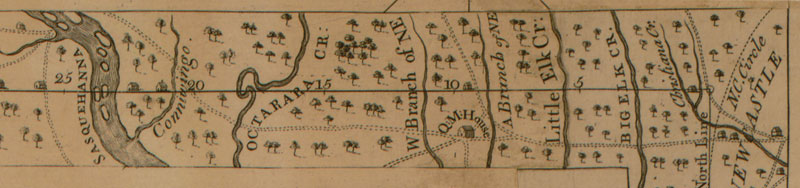

Standing on a small hill overlooking Dunkard Creek, Charles Mason and Jeremiah Dixon aligned their latest survey post “and heaped around it Earth and Stone three yards and a half diameter at the Bottom and five feet High.” The conical monument was about thirty miles short of Pennsylvania’s southwest corner and “233 Miles, 13 Chains and 68 Links” from their starting point, “the Post mark’d West.” Behind the forty-man survey crew lay several hundred miles of near impenetrable Pennsylvania woodland; ahead were wandering bands of Shawnee marauders, the mortal enemies of their Iroquoian escorts. If Mason and Dixon continued to push the line west to its completion, as their financial supporters back in England had requested, they were sure to find themselves embroiled in an Indian war. The leader of the native guides recognized the danger and took issue with the surveyors’ hesitation to call a halt to their fieldwork. His emphatic declaration that he “would not proceed one step further Westwards” left the Englishmen with only one option. Dunkard Creek would have to be the end of the line.

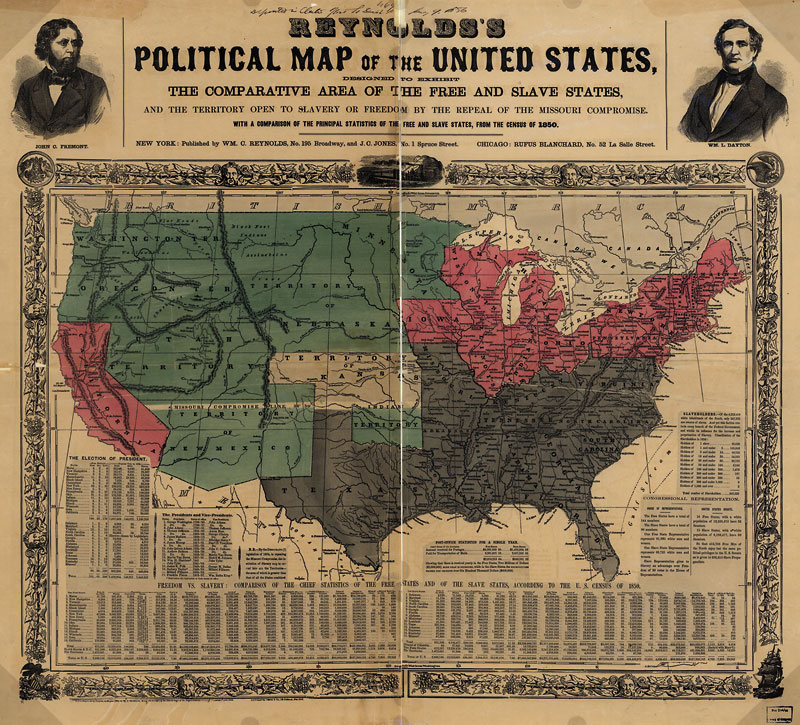

The 1763–67 survey by Mason and Dixon marked the culmination of an eighty-year border dispute between Pennsylvania and Maryland—a dispute which at times had degraded into some of the worst bloodshed witnessed on the American frontier. When the lands were originally awarded in the mid-to-late seventeenth century to two of England’s aristocratic families, the Penns and the Calverts, ambiguous wording in the royal grants and faulty maps misplaced Maryland’s northern border within the limits of Philadelphia. A clear interpretation of the grants was obviously required, along with a demarcation of the border on the ground.