Walk the Line

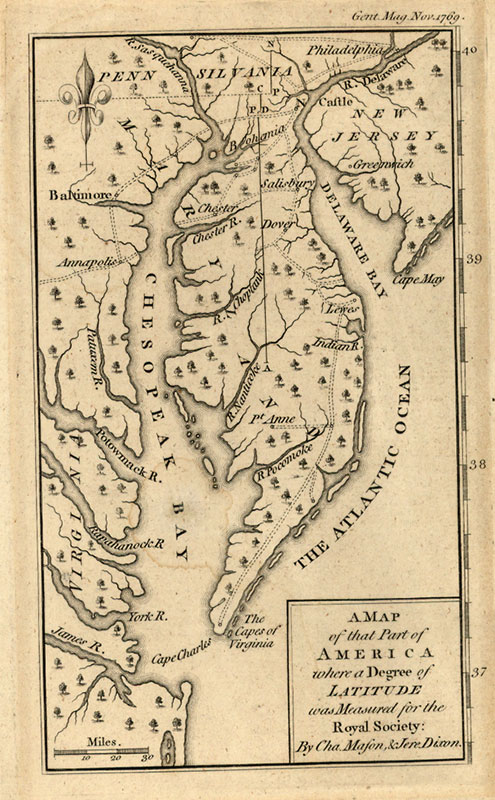

Colonial surveyors had tried to establish the border several times before Mason and Dixon arrived on the scene, but their limited knowledge of spheroid trigonometry made the task impossible. Their instruments were not much help either. Even the celebrated Jersey quadrant, probably the most accurate instrument in the colonies, was good to only one-half arc minute, the equivalent to about 2,600 feet on the ground. The Penns and the Calverts appealed to the Astronomer Royal in Greenwich “to send from England some able Mathematicians with a proper set of Mathematical instruments.”

England’s top astronomer selected Charles Mason and Jeremiah Dixon, two junior colleagues who had already distinguished themselves as talented professionals with their detailed measurements on the 1761 transit of Venus (see Fine Books & Collections, summer, 2012). Charles Mason was an assistant astronomer at Greenwich where he was working on a monumental star catalogue that would improve the accuracy by which navigators could find their longitude and latitude. Jeremiah Dixon was an outstanding mathematician and county surveyor.

Mason and Dixon arrived in Philadelphia in November 1763, accompanied by a shipload of the best surveying instruments England had to offer, among them were two transits; two reflecting telescopes “fit to look at the Posts in the Line for ten or twelve miles;” a Hadley’s quadrant; astronomical clocks; star tables; several sixty-six-foot Gunter chains; ten-foot measuring rods made from precision-cut softwood, tipped with brass, and equipped with a builder’s level; and a zenith sector with a six-foot radius.

The sector was their most precious instrument. It was essentially a telescope fitted with micrometers that were capable of measuring the angular distance to stars. The Mason-Dixon sector was built by the London-based John Bird and was a scaled-down version of the most accurate astronomical instrument then in existence, the twenty-five-foot zenith sector at the Royal Observatory. The smaller, highly sensitive instrument was accurate to within two arc seconds (less than two hundred feet on the ground), and would have to travel the deeply rutted trails of New England’s backwoods on a feather mattress set above the springs of a single-horse, two-wheeled cart.

To ensure the measuring rods were in calibration Mason and Dixon also carried with them a brass standard that was a duplicate of the one held under lock and key in the Tower of London. Every morning and afternoon, Mason and Dixon used a microscope to compare the lengths of the four measuring rods to the standard, which probably measured to within .01 of an inch. Any differences in the rods were duly noted in their notes along with the ambient temperature since contractions in the rods caused by cold temperatures could leave a discrepancy of as much as fifteen inches per mile.