The Big Sell

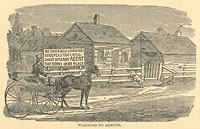

Long before giant superstores, peddlers wandered rural back roads hawking every kind of book imaginable. And they didn’t always get what they were promised. By Jeffrey S. Murray

“I have just returned from answering an ‘ad’ for a book agent,” wrote a young Elizabeth Lindley in her diary. “Am perfectly delighted with the contract I made, and now feel that I was very stupid to have wasted so much time grieving in poverty on account of my pride.” For a $3.00 outlay, Lindley was given a sample copy of the book she was expected to peddle throughout New York State—a fine, leather-bound, limited edition of the works of William Shakespeare—and was guaranteed a princely salary of $35.00 a week. “Just think of it,” continued an elated Lindley. “Why, I can live well, dress swell, and save a little for a rainy day.” 1

By the early 20th century, peddling had already helped sell 2.5 million copies of Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry Finn.

Door-to-door peddling was a long-established method of distributing books when Lindley signed her contract in the early decades of the 20th century. The system had already helped to sell 2.5 million copies of Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry Finn, and 320,000 sets of President Grant’s two-volume memoirs. Even as late as the 1940s, door-to-door selling was a popular method of introducing new titles to an estimated 30 million Americans without direct access to a library or book retailer. Today’s in-home encyclopaedia salesman is the last vestige of an industry that at one time extended to the four corners of the continent.

It seems most canvassers were attracted to the business through newspaper and magazine advertisements that promised liberal reimbursement. But before they could begin knocking on doors, would-be agents were expected to invest from $1 to $5 in the publisher’s sales kit. These kits usually included a complete copy of the book, a sales prospectus, a how-to-sell pamphlet, and various publisher’s handbills.

In exchange for the kit, agents received exclusive rights to canvass a single title in a specified territory, but the canvass had to be undertaken at the agent’s own expense. For each title sold, agents received a commission, from which they deducted their transportation, room and board, and all shipping costs from the publisher. If a customer died, moved, or learned how to hide from canvassers, the agents were expected to cover the loss.

By far the most effective tool in the sales kit was the prospectus. Containing a few sample pages from the original publication, the prospectus was akin to a modern-day movie preview: a tantalizing snippet of great things to come. Being much shorter than the original publication, the prospectus had the added advantage of being considerably more transportable on rural back roads. More importantly, it had plenty of room to list all the subscribers who the agent had talked into purchasing a copy of the complete book.