The Gift of Closure

World War II veteran returns books to Germany after more than sixty years

By Christopher Lancette

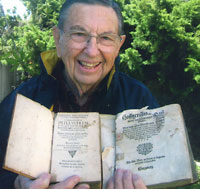

credit: Shirley Dowe, courtesy of Robert Thomas

In April 1945, United States Army private Robert Thomas rode through a German village on a motorcycle and couldn’t quite understand why townspeople were holding white flags and trying to surrender to just him and a lieutenant. In the next few hours, he twice encountered German men in lab coats whom he later learned were actually soldiers concealing automatic weapons.

“We came to the conclusion that they thought we were advanced scouts of a large American force or they would have killed us,” Thomas reflected, some 64 years later.

He was chosen for the reconnaissance mission to explore the village while he was recovering from combat wounds. What they found was one of Germany’s notorious salt mines.

The mine director waived off the German soldiers and allowed the two members of Gen. George S. Patton’s Third Army to inspect the contents of the mine, 2,500 feet below ground. Bathed in nearly blinding light, it contained perhaps two million books that were part of a hidden bounty of German national treasures. A self-described “book nut” since he fell in love with the Long Beach Public Library in California as a kid, Thomas decided to take a pair of parchment-covered books as war trophies – choosing two that looked old and important. One was a commentary in Latin about Roman law published in 1593, and the other a German-language review of court administration in the Duchy of Prussia, published in 1578.

Thomas shipped out before he ever learned the location of the spot where he had spent those mysterious two days. For the next six-and-a-half decades, he carefully preserved the books and hoped they would unlock clues to his past.

“I briefly considered selling the books or passing them down to family, but I didn’t think much about their value,” said the 83-year-old Thomas, now a retired optometrist living in Chula Vista, California, who volunteers as a docent at the USS Midway Museum in San Diego. “I felt that if I could talk to somebody about these books–trace the books down–I could make sense of my experience those two days.”

When he read news of the discovery of a storage mine near Merkers, Germany where the Nazis had stored more than $500 million in German gold, art, and other items, Thomas returned to his quest. He contacted Greg Bradsher, a senior archivist at the National Archives in Washington D.C. and an expert in looted World War II artifacts. Bradsher spent months researching the books and successfully uncovered the name of the village where Thomas encountered white flags and rare books: Ransbach.

“Greg solved my two lost days,” Thomas said, his voice filled with gratitude and relief.

Bradsher suggested that Thomas return the books to their country of origin. Thomas received the same advice from the Monuments Men Foundation, an international organization based in Texas that is dedicated to locating and returning cultural treasures stolen during World War II.

The former GI was easily persuaded. Returning the two sixteenth-century volumes (one was traced to a library in Bonn) would honor his love of his childhood library, where he said he spent so many hours marveling at the fact that he could “borrow books about any subject and read about it.”

Bradsher arranged a formal ceremony with the U.S. Department of State and German Ambassador Klaus Scharioth at the National Archives last month.

“I was glad to see the books returned,” Bradsher said, noting that it’s not often that someone is as generous as Thomas. “Books and all cultural properties really belong with the country or institution where they came from, as part of their culture. Taking them away is like taking a little piece of their heritage.”

It felt good to Thomas, too.

“I was reluctant to turn the books in until the two days were solved,” he said. “Once I knew what happened to me all those years ago, I decided it was the right thing to do. I wanted the books to go back to their homes.”