Composing a Collection

Take away the rock stars, and music offers unexpected variety and opportunity for collectors By Joel Silver Joel Silver is Curator of Rare Books at the Lilly Library.

With the tremendous popularity of music of all kinds over the centuries, and the large amount of printed and manuscript music that has been produced, there are many possibilities for collectors who want to get started in this field. Collectors approaching music for the first time may be both surprised and bewildered by the breadth and depth of what is available. Like other areas of the performing arts, the primary works themselves can be endlessly supplemented by a vast array of ephemera, autographs, and pictorial material.

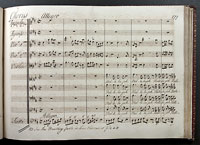

Most of us first encountered music books in the form of sheet music, school songbooks, or instrumental pieces, but the earliest music was produced in manuscript form, and manuscript music predates printed music by many centuries. Though music from the earliest era is usually unobtainable, there are still opportunities for collectors to acquire later medieval manuscript music as it appeared in psalters, missals, and other service books. Complete medieval manuscripts of any kind are generally too expensive for most collectors, but many manuscripts have been (and even continue to be) broken up, and the individual leaves can sometimes be found for a few hundred dollars, which may well be within a collector’s reach.

As is the case in any area of collecting, a collector’s own interests should be the primary factor in deciding how to form a collection, but the availability and price of potential acquisitions form the practical daily backdrop to any collecting pursuit. In the field of music, as in other fields, the market has been shaped by what has survived, how collectors and scholars of the past and present have viewed these objects, and how the availability of material today has been affected by what has gone into institutional libraries, and has thus been removed from the market.

In this respect, antiquarian music is not very different from any other book-collecting field—if it’s famous, and you’re interested in first editions, it’s likely to be popular among collectors and expensive to acquire. This hasn’t, however, always been the case in music collecting. Book collectors are often looking back to a more glowing past, but you don’t have to look too far to find a golden past in music collecting. In 1934, John Carter edited New Paths in Book Collecting (London: Constable), an influential and interesting anthology of essays by various authors, on collecting fields that were not within the then-current collecting mainstream. The untrodden fields discussed in the book included, among others, such now heavily collected subjects as detective fiction, American first editions of the period 1900-1933, and English book illustrations from 1880-1900. The book also included an article by bibliographer, librarian, and collector, C. B. Oldman, on “Musical First Editions,” which was described as being the first effort of its kind in English. Oldman included a great deal of information on the first editions of some of the works of major composers, and he pointed potential collectors toward many of the standard reference works and bibliographies in the field. He was also careful to say that there was still a great deal to be done in the field of music bibliography, and this is still the case today. Oldman concluded his essay with some timely advice to collectors:

“At its present stage, musical bibliography may be one of the most tantalising, but it is also one of the most fascinating of hobbies. Enough is known to make a start possible, but not enough to take away the joy of discovery. And the collector need not fear that his hobby will make undue demands upon his purse. Musical first editions are still ridiculously cheap. Very few cost more than a few pounds and many can still be picked up for a few shillings. But the market is becoming more and more organised—it is no longer possible to find first editions of Handel in the sixpenny tub, which was where I discovered a few years ago the only first editions of Handel that I possess—and before long the speculative buyers will come rushing in and prices will begin to soar. For the collector of moderate means there is no time like the present. If he waits too long he will find that another ‘new path’ has already been closed to him.”