Charting the Waters

Surveying the coastline, however, was only the beginning. The data still had to be put on paper. During the winter months, Des Barres and his assistants drafted the season’s work at his home, Castle Frederick, near present-day Windsor, Nova Scotia, then went back to the coast and compared the drawings to the actual landmarks, especially with regard to bearings. “I went along shore,” wrote Des Barres in a letter to senior British command in 1765, “and reexamined the accuracy of every intersected object, delineated the true shape of every head land, island, point, bay, rock above water, etc and every winding and irregularity of the coast; and, with boats sent around the shoals, rocks and breakers, determined from observations on shore, their position and extent, as perfectly as I could.”

After ten years of fieldwork, Des Barres returned to England in 1774 to prepare his surveys of Nova Scotia and New Brunswick for publication. With a revolution looming in the American colonies, the Admiralty made it clear that it required a more comprehensive work. To this end, Des Barres began planning a marine atlas for the entire eastern seaboard, which he entitled The Atlantic Neptune. Eventually the atlas would include the surveys of at least a dozen other hydrographers–their contributions are acknowledged in the each chart’s title block–and would cover the waters from the Labrador Sea south to Florida, Louisiana, and parts of the West Indies.

In the eighteenth century, the cost of engraving a map in Britain, depending on its complexity, averaged from £2 to £30, but the Admiralty allowed Des Barres nearly £37. Although Des Barres left no indication as to how much time was spent engraving each of the 247 plates used in his Atlantic Neptune, it was not unusual for some of his contemporaries to take as much as a year and a half to two years to complete a complicated plate. One historian has suggested that, with a complex map, an eighteenth-century engraver might be expected to produce only one square inch a day.

In just three years, in 1777, Des Barres was ready with the first edition of his atlas, which was divided into five parts: Book I consisted of “impressions of all the charts plates of my surveys of the coast and harbors of Nova Scotia, with a small book of tables of latitudes, longitudes, variations of the magnetic North, tides etc.;” Book II contained “charts of the coast and harbors of New England composed, by command of Government, by various surveys, but principally from those taken by Major Holland under the directions of my Lords of Trade and Plantations;” Book III comprised charts of the Gulf of St. Lawrence, and the islands of Cape Breton and St. John; Book IV, the coast of North America south of New York based on several surveys; and Book V, “various views of the North American coast.” In later editions of the atlas that were published in 1780, 1781, and 1784, the aquatint views found in Book V were incorporated into the appropriate first four volumes.

Praise for The Atlantic Neptune came from all corners of Europe. A reviewer of the 1784 edition published in L’Espirt des Journaux, Paris, called it “a superb Atlas … indispensable for the navy … of the highest degree of beauty and superior to everything of the kind that has heretofore been published … of the highest possible utility for navigation and commerce.” Another reviewer called the atlas “the most splendid collection of charts, plans and views ever published.”

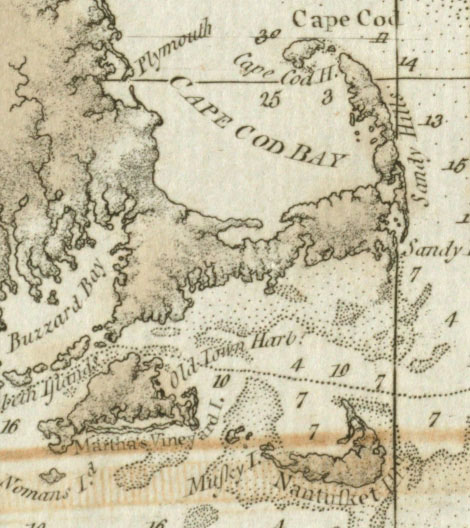

Perhaps the greatest tribute was in knowing that his charts were helping to make eastern waters safe. Captain Hyde Parker of the Phoenix was among those grateful for their existence. Having been tossed about in a storm for three weeks in 1778 and unable to make astronomical observations, his officers believed they were somewhere off Cape Cod, but after taking a few soundings and comparing their readings to the Des Barres charts, they realized the Phoenix was quickly approaching the dreaded Sable Island. A change of course saved the ship and crew from certain disaster.