Charting the Waters

Joseph F. W. Des Barres mapped North America’s northeastern coast as revolution loomed and then sailed back to England to publish his monumental marine atlas, Atlantic Neptune By Jeffrey S. Murray Jeffrey Murray is a former senior archivist with Library and Archives Canada, Ottawa, Canada, and the author of Terra Nostra: The Stories Behind Canada’s Maps, 1550-1950 (Montreal, McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2006).

Joseph Frederick Wallet Des Barres was one of the new breed of surveyors who were slowly making their way into His Majesty’s service in the mid-eighteenth century: foreign born, well educated in the sciences and mathematics, and thoroughly trained in the art of surveying. Following his studies at Britain’s Royal Military Academy, Woolwich, the Swiss cartographer’s abilities were rewarded with a promotion to lieutenant and a posting in 1756 to the Royal American Regiment of Foot. Through a special act of Parliament, the four battalions comprising the recently formed regiment were to be recruited in North America from German colonists, but enlistment was poor and the difference (more than half) had to be made up by accepting men rejected by other British regiments in Ireland. Using open formations and native methods of forest warfare, this unlikely collection of colonists and cast-offs quickly gained the upper hand over the French and their Indian allies at Schenectady, Lake George, and Ticonderoga. Two years later the Regiment proved itself again at the siege of Louisbourg on Cape Breton Island, Nova Scotia.

Using documents captured after the fall of Louisbourg, Des Barres compiled a large-scale chart of the St. Lawrence River and Gulf, which proved indispensible in moving the British fleet to the doorstep of the French capital at Quebec the following year. Four decades earlier, Britain had launched a similar campaign against the strongly built fortress but, without the aid of detailed charts, the 60-ship fleet easily floundered on hidden shoals. The invaders eventually had to admit defeat and retire back to Britain without firing a single shot. Through Des Barres’ diligence, however, the British were able to pass its ships of war and successfully wrestle control of the capital. The British victory not only demonstrated the utility of accurate marine surveys, but also the role Des Barres could play in their preparation.

With assurances of further promotions and a salary of twenty shillings a day, Des Barres was seconded to the British Admiralty in 1763 to undertake a detailed nautical survey of the New Brunswick and Nova Scotia coasts. Des Barres (also spelled DesBarres) understood that a truly accurate marine survey must first begin on shore and must use the system of triangulation. He started by using a theodolite to establish a base line of 350 fathoms (about 645 metres) along the shore. The end points of this line would be fixed, using a quadrant to calculate their latitude and longitude. He then used this baseline to take a series of readings on distant points along the shore. This procedure allowed Des Barres to set up a series of intersecting triangles, and confirm the position of each measurement through trigonometry. As long as the length of one side and two angles of his triangle were known, the position of distant points, which normally would have been un-measurable, could be accurately determined. Once all the points were plotted, a draftsman could then sketch the shoreline between them.

Readings on the depth of the ocean floor were taken by a lead weight attached to the end of a hemp line. The weight was dropped into the water and when it hit bottom, the depth of the ocean floor could be estimated (in fathoms) by the length of rope that had been let out. Sometimes a core of tallow was set into the weight. The sticky tallow picked up debris from the ocean floor, giving the mariners some indication of its consistency.

Because of the irregularity of the shoreline, the work was often exceedingly tortuous. “There is scarcely any known Shore so much intersected with Bays, Harbours and Creeks as this is, and the Offing of it is so full of Islands, Rocks and Shoals as are almost innumerable,” complained Des Barres. The work was also hazardous. The larger survey ships had limited maneuverability close to shore and always ran the risk of hitting uncharted rocks and shoals, the very features they were there to investigate. Smaller boats, as Des Barres discovered, could easily swamp in the unpredictable conditions of the North Atlantic.

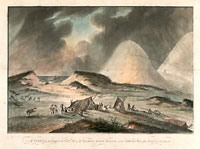

His survey of Sable Island off the southeast coast of Nova Scotia was accomplished under extremely perilous conditions. Situated about 90 nautical miles off Nova Scotia, the fog-bound, low-lying dunes that make up Sable Island lie directly across the shipping lanes between Europe and New England. The mile-long island had already claimed more than 200 known ships by the time Des Barres arrived to chart its shoals (the number of unrecorded tragedies is thought to be much higher). “This survey the Author has accomplished at the Hazard of his life,” wrote Des Barres, “the surf upon the Shores admitting no boat to approach without the greatest risk.”