Paper Chase

An original Bill of Rights mysteriously disappeared in 1865. When it reappeared some 138 years later, the asking price was $5 million, and the FBI took note. By Rebecca Rego Barry Rebecca Rego Barry is the editor of this magazine.

Lost Rights: The Misadventures of a Stolen American Relic

David Howard; Houghton Mifflin Harcourt; 344 pages; hardcover; $26

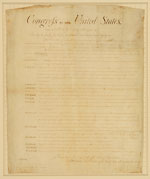

In David Howard’s engrossing true-crime tale, one historic document stands front and center: the Bill of Rights. More specifically, the Bill of Rights that is most likely North Carolina’s once-missing copy. Only fourteen parchment originals of the Bill of Rights were penned, one for each state and one for the federal government. Several have gone missing over the years, and at least one (New York’s) was destroyed in a fire. North Carolina’s copy left the state in 1865, when, as the story goes, a Union soldier pilfered it as war booty (damn Yankees!). The document was later sold for $5 to Charles Shotwell, who framed and displayed it in his Indiana home for the rest of his life.

Fast forward to the 1990s when Shotwell’s granddaughters, nearing retirement, realized the document might be worth more than anyone dreamed. Perhaps with Antiques Roadshow in mind, the sisters—knowing little about the document and even less about the historic document business—began looking around for a buyer. What they ended up with was a wily antiques dealer from Connecticut named Wayne Pratt, of Roadshow celebrity, who gave them far less than he thought it was worth, and yet assumed all the risk regarding the document’s suspicious provenance. If someone could prove that the copy was truly North Carolina’s, he would be unable to sell it, and the state could demand its return through its strict replevin laws. But Pratt always believed he could make millions on it, and he convinced many others to back this incredible opportunity.

As Howard peels away at the history of this artifact, he reveals the way it touched the lives of everyone involved—the previous owners, historians, lawyers, political figures, antiques dealers, real estate developers, museum officials, and historic document experts Seth Kaller, Bill Reese, and David Redden. In this story, obsession, greed, and betrayal stand against (though sometimes mingle with) wisdom, diligence, and honesty. It is human nature writ large.

Anyone who followed the news of the document’s discovery and seizure by the FBI will remember how it all turned out and will, no doubt, have opinions on who was in the right. Even so, Howard delivers intriguing details through exhaustive interviews, court documents, and historic and contemporary press coverage that are sure to make one think twice. Howard is a faithful reporter, allowing readers to make their own conclusions from the material he presents. In the postscript he writes, “Pratt’s involvement with the Bill of Rights ultimately has a Rashomon-like quality, with different onlookers divining different realities. Some see an innocent victim taken down by power-hungry government opportunities; others see a conniving carpetbagger or a scheming rat; still others view him as an ambitious, hard-driving entrepreneur who simply took bad advice.”

There is but one stumbling block to full enjoyment of this book, and that is the lack of photographs. Whether weaved into the text or printed in a separate insert, readers would have greatly benefited from a handful of accompanying photos, e.g. the Bill of Rights in question (or any original), the hand-written docketing that provided the most effective material evidence, and a photograph of Charles Shotwell, Wayne Pratt, John Richardson, Ken Bowling, or any of the other fascinating people whose lives became entwined with this very special piece of parchment. The absence of images is simply illogical—almost unforgivable!—and yet, the narrative zips along, satisfying its reader.

Clearly Howard, the executive editor of Bicycling magazine, is a skillful researcher, reporter, and writer, and in Lost Rights, he has produced a story that is both suspenseful and thought provoking. For collectors, dealers, archivists, and armchair historians, his book has much to offer, not the least of which is a poignant cautionary tale.