Going Postal

The extraordinary story of an eccentric collector

By Ellen F. Brown  Ellen F. Brown is a freelance writer who specializes in stories about antiquarian books and the fine arts. Her forthcoming book is called Margaret Mitchell’s Gone With the Wind: A Bestseller’s Odyssey from Atlanta to Hollywood.

Ellen F. Brown is a freelance writer who specializes in stories about antiquarian books and the fine arts. Her forthcoming book is called Margaret Mitchell’s Gone With the Wind: A Bestseller’s Odyssey from Atlanta to Hollywood.

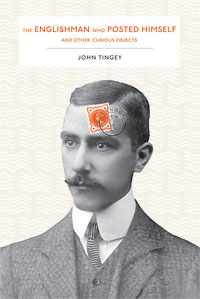

The Englishman Who Posted Himself and Other Curious Objects

John Tingey

Princeton Architectural Press

175 pages

hardcover

$24.95

Conducting interviews for the “How I Got Started” column in Fine Books & Collections is a great job. I never tire of hearing about people bit by the collecting bug and the creative ways they pursue their passions.

Imagine my delight then in discovering The Englishman Who Posted Himself and Other Curious Objects, a gem of a book about W. Reginald “Reg” Bray, a British philatelist and autograph collector who also amassed a remarkable collection of postal curiosa in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The book is actually a tale of two collections: how Bray created his assemblage of oddities and then the modern-day attempts of the book’s author, John Tingey, to acquire Bray-related items, many of which found their way to market after the death of Bray’s wife.

The book is akin to one long “How I Got Started” profile. In 1898, at the age of twenty, Bray obtained a copy of the Post Office Guide, a government publication that described in punctilious detail the services, fees, and regulations of the British post office. He thoroughly studied the manual, fascinated by its guiding principle that mail carriers were required to deliver all mail, including even live animals, so long as it was clearly and legibly addressed. In Tingey’s words, “Bray viewed these rules as challenges, opportunities to determine how far the post office would go to comply with its own regulations.”

Bray spent the next ten years mailing thousands of unwrapped oddball objects to see how the postal service would react. He shipped a slipper, a clothes brush, a pipe, and even a rabbit’s skull, in each case using ingenious ways to address the items. He attached a luggage label to an onion. He carved an address into a turnip. In other instances the fun was in the stationary he used. Shirt collars and cuffs were cut into postcards. Bray’s mother crocheted envelopes with the recipient’s name integrated into the pattern. Tingey takes particular pleasure in Bray’s outlandish experiments with addressing his correspondence. Many a postman must have puzzled over locations described in verse or written backwards. “How the sorters must have invoked the gods on my head when they caught site of my innocent postcards,” Bray once wrote. The prankster’s pièce de résistance was his successful invocation of the “living letters” regulation to mail a dog and even himself.

The disposition of Bray’s collection and how Tingey discovered it add further interest to an already fascinating account. Equally engaging as the narrative are the illustrations. The Englishman is an attractive volume, overflowing with photographs of Bray-iana and the man himself up to assorted hijinks. My favorite is an image of him being delivered to his father’s house. I’ve studied it numerous times trying to decipher the inscrutable faces of the earnest looking mailman and the senior Bray while Reg stands by with the barest hint of a mischievous twinkle in his eye.