Atomic Scribblings from a Maniac Age

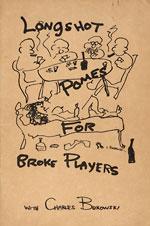

His artwork was similarly showcased in underground newspapers, little magazines, and small press publications in the ensuing decades. The most remarkable case would be Los Angeles Free Press, where his fiction and poetry was championed in over two hundred issues, most of them featuring his illustrations, including several comic strips titled “The Adventures of Clarence Hiram Sweetmeat” that Black Sparrow Press and Paget Press would subsequently issue in limited editions, such as Dear Mr. Bukowski (1979) or The Day It Snowed in L.A. (1986). Bukowski seemed to effortlessly produce so many “The Adventures of Clarence Hiram Sweetmeat” cartoons that in the early 1980s, when he was no longer contributing to the Los Angeles Free Press, he suggested to the High Times editors, who were publishing Bukowski’s short stories on a monthly basis, that he could revive those cartoons for their magazine, but the project never crystallized.xix The “littles,” however, did promote his art, which appeared in the main pages of literally hundreds of issues and even on the front cover of alternative publications such as The Sunset Palms Hotel (1974), The Moment (1990), or the New Censorship (1991), to name a few.

Likewise, booksellers used Bukowski’s drawings to illustrate their catalogues, hence increasing their value. Jeffrey Weinberg recalled that Bukowski was “cooperative, friendly and humble,”xx and selflessly sent him a poem and several drawings for Under the Influence, a Bukowski-only catalogue released in 1984; three years later, in spite of the success brought about by the movie Barfly, Bukowski was generous enough to give away his artwork to a bookseller in Canada: “I decided to produce a list of my Bukowski holdings for collectors, inviting Hank to contribute a cover drawing. He doodled up four submissions—of which I used two.”xxi It seems evident that editors and publishers alike valued Bukowski’s art throughout his career by printing his unmistakable drawings and doodles or, as in the case of Black Sparrow Press or Loujon Press, by selling limited editions of his books with unique paintings that would turn them into highly priced collectibles over time.

Indeed, John Martin, Bukowski’s longtime publisher and editor at Black Sparrow Press, realized from the very onset of their “unholy alliance” that Bukowski’s art would be financially profitable: ninety original drawings by Bukowski were tipped-in to the limited edition of their first lengthy literary venture, At Terror Street and Agony Way (1968), which was soon to become a much coveted possession by collectors. Shortly before The Days Run Away Like Wild Horses Over the Hills was released in late 1969, Martin asked Bukowski to produce fifty illustrations for the signed, numbered edition, hardbound in boards, of the first comprehensive bibliography of his work, A Bibliography of Charles Bukowski (1969). Although painting was apparently the easiest art form for Bukowski, as recounted in the short story “East Hollywood: The New Paris,” he would occasionally complain about the fact that Martin commissioned him dozens of illustrations for each new book, as if they were strictly compulsory. Moreover, he was acutely aware of Martin’s ulterior motives: “I threw 30 paintings in the garbage and Martin just about killed me. I’ve never seen the man so distracted … He claims I threw away 2 or 3 grand. Now, Sanford, you know I didn’t throw away 2 or 3 grand, I threw away some paintings that didn’t look good to me,” he explained to his bibliographer in 1970xxii – the next day he sent a similar letter to poet and friend Harold Norse, mocking Martin’s financial concerns. Even though Martin’s businesslike vision of his art, where paintings equated with easy money, seemed to disappoint Bukowski, he continued to duly create hundreds of illustrations and drawings for Black Sparrow Press up until his death in 1994. Painting was, ultimately, a compulsion tantamount to writing, a most incurable disease he adamantly refused to fight against.