Atomic Scribblings from a Maniac Age

The lost artwork of Charles Bukowski By Abel Debritto Abel Debritto lives in Spain.

By 1966, Charles Bukowski’s work was featured in so many “little magazines” that he was soon to be hailed as a “spiritual leader” of the so-called mimeograph revolution that was taking place across the United States. His poetry was unabashedly promoted in hundreds of alternative periodicals, which would eventually earn him the indisputable honor of being the most published author of the decade. Shortly before the mimeo revolution reached its peak, Bukowski began to work on an unusual project titled Atomic Scribblings from a Maniac Age. While Bukowski had illustrated some of his previous publications, such as Longshot Pomes for Broke Players, Atomic Scribblings was to be the first book where his artwork would be predominantly showcased, with a few interspersed poems, thus turning the volume into a rara avis in the Bukowski canon.

However, despite Bukowski’s intense, passionate involvement in the project, it was finally aborted when the publisher, Wayne Philpot, vanished with Bukowski’s drawings in 1966. Philpot, who had printed Bukowski’s poetry in his little magazine, Border, in January 1965, was probably stunned by the quality of the drawings and doodles Bukowski selflessly decorated his lengthy letters with—Bukowski profusely illustrated his correspondence and short stories from the mid-1940s onwards. Philpot requested several drawings and one of them, titled “Sunday Afternoon In Heaven,” graced the front cover of Border #2 in April 1965. Bukowski’s illustrations had such an impact on Philpot that it immediately prompted him to tackle the book of drawings and poems: “I have a proposition that may … or may not … interest you … Border Press … would like to bring out a limited edition of Buk’s drawings (black & white) with only a few poems along w/them (4 or 5).”i Bukowski gladly complied by sending dozens of drawings to Philpot during the ensuing months. Bukowski was corresponding with several authors and editors at the time, and he would discuss the ongoing project with them; as he confided to Canadian poet Al Purdy in June 1965, he had already begun “a book of poems and drawings, mostly drawings, untitled and undone so far, but that I will work up in a couple of months for Border Press.”ii In an undated letter to Steve Richmond, Bukowski mentioned the volume again: “[I am] now working on a book of black and white drawings for Border Press … have got 20 or 30 into him already.”iii Bukowski so enthused about the notion of having his drawings published in book form that he even showed them to Henry Miller in August 1965. Two months later, in a letter to Purdy, he would declare that he was “still working in my book of drawings for Border.” iv In another undated letter from Philpot to Bukowski, probably from late 1965, he listed the fifteen drawings he had accepted so far for the book: “Easel of a Fanatic with Indigestion,” “The Death of Karl Marx,” or “Portrait of a Dog Elected to a Senatorial Seat” were the titles of some of the drawings to be published in Atomic Scribblings.

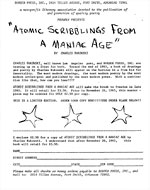

Promotional flyers, order forms, and advertisements were issued in late 1965. However, in a common, yet infuriating practice among small presses and little magazines, the project came to nothing without a single explanatory note to the parties involved. Bukowski, who had undergone similar experiences, such as a joint William Corrington/Charles Bukowski chapbook cancelled by Marcus Smith in 1962, suspected that Philpot’s artistic enterprise would not be completed, as he remarked to Douglas Blazek, who had advertised Atomic Scribblings in Olé in early 1966: “Please do not run any more ads … this guy does not respond to inquiry and evidently isn’t going to publish the thing, yet he’s hooking all the $3.50’s [retail price] that come in and make me look like a crook.”v Almost six months later, Bukowski would confirm his suspicions to Marvin Malone, an editor he overtly admired, as opposed to Philpot and other editors who did not seem to take publishing seriously enough: “I like to play with drawings. Did over a hundred for some guy in Arkansas who was going to bring out a book of them, but no word from him in a couple of years, no response to inquiry, no return of drawings, no book. Where do these guys come from?”vi A year later, in November 1967, he would sum up the episode to Allen De Loach, editor of Intrepid, where his work would appear in the late 1960s and early 1970s in several issues of that little magazine: “I sat up night and day for 3 weeks, drunk, naked, laughing to myself, awakening in the morning … covered with india ink … I gave him a title … Atomic Scribblings Upon a Farting World and mailed the batch to him. I saw ads for the book here and there. I wrote Wayne. No response.”vii Apparently, Bukowski concluded, for some unfathomable reason, Philpot burned all the drawings.