Fields of Gold

A century ago, misleading maps drove southerners to seek their fortune in the Yukon By Jeffrey S. Murray Jeffrey S. Murray is a former senior archivist with Library and Archives Canada.

“On looking at a map, it seems the easiest possible job to follow the right course, but in fact it is rather more difficult than it looks,” reported James Shand in an open letter to the readers of the Edmonton Bulletin. Shand and his three companions were among the throng slowly making its way from Edmonton, in present-day Alberta, to the gold fields of Alaska and the Yukon. They were anxious to cash in on what was widely hailed as the biggest gold find in history. Although considered seasoned northern travelers, the Shand party had considerable trouble finding its way through the maze of creeks and rivers that made up the Mackenzie and Athabasca Rivers. Their map often led them in the wrong direction, causing unnecessary delays and adding unwanted miles to their exhausting trip.

The difficulties that Shand faced were not uncommon for would-be prospectors of 1897. The maps made available to them were often little more than promotional pieces for those southern businesses—the transportation companies and large outfitters, in particular—that stood to make fortunes servicing the needs of the Yukon-bound gold seekers.

The intent of the promoters was to encourage as many people as possible to participate in the rush to Dawson City and the Klondike River, the center of the Yukon gold trade. It is not surprising that their Yukon maps emphasized the vastness of the Klondike gold fields and their easy accessibility from the south. The maps often provided information on dozens of routes linking southern “gateway” communities to the Yukon interior. Inevitably, these routes—they were actually only trails—were marked as if they were the equivalent to a major railway or transportation corridor in the south. All were given the same consideration, even those that existed on paper only and were life-threatening for novices of wilderness travel. The maps offered no warnings to Klondike-bound fortune hunters about the hardships they could expect to encounter.

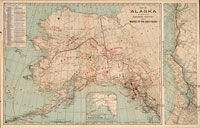

The most common type of map produced by promoters of the gold rush covered the entire northwestern portion of the continent (Alaska, present-day Yukon, and British Columbia). Without exception, the maps portrayed the region as a vast landscape, completely void of a native presence, but full of riches ready for the taking: all the unexplored river valleys were labeled as “gold fields,” and the entire region colored yellow, just like the gold they were flaunting. Often areas which experienced earlier gold strikes, such as the Omineca, Cassiar, and Cariboo regions in central British Columbia, and which would be familiar to nineteenth-century adventurers were also marked. All these areas were labeled with the same typeface as that marking Dawson City, thereby giving the mistaken impression that they were of equal importance.

Map publishers found the Klondike gold rush to be a very lucrative source of new business. Since so little was known in the south about this remote corner of the continent, the southerners were naturally desperate for any information they could find, and maps were particularly high on their lists. The Province Publishing Company of Victoria and Vancouver, British Columbia, was among the first to hit the newsstands along the west coast with a map of the Klondike. Their four-color wall map was produced in three formats: a paper edition that sold for fifty cents, a mounted edition that sold for seventy-five cents, and a waterproof edition that sold for one dollar. None of these prices were insignificant considering a night in a Vancouver hotel cost about one dollar and a meal about twenty cents. Despite its high price, the map quickly went into a second, revised, printing of one hundred thousand copies, and eventually a third edition was done as well.

Apparently, some treasure seekers were willing to pay almost anything for a map of the gold fields, particularly if they felt it gave them an advantage over their fellow treasure hunters. One group of gold seekers, met by Charles Camsell on the trail out of Edmonton, admitted to paying $300 for their sketch map of the gold-bearing creeks in the Yukon. Having grown up at a northern fur trade post, Camsell was initially surprised by their naiveté, but before long he found several others with copies of the same map, which “the vendor must have sold to dozens of prospectors for the same amount. In one case,” continued a shocked Camsell, “the owner of the map told me he had got it from a friend while the two of them were engaged in shingling a barn in the Okanagan country in the State of Washington. The maps were no good as these fellows found out later, and the person who sold them was probably never at the locality in his life.”

Given the types of maps circulated, it is perhaps to be expected that many fortune seekers were terribly optimistic about how easy it would be for them to get to this fringe of the frontier. Alphonso Waterer came across just such a group in front of an Edmonton hotel. “A bunch of men were discussing the Yukon, and were most anxious to learn where we came from and how we proposed reaching Alaska,” he recalls in his memoirs. “They were a motley crowd and most of them rather too inquisitive from our point of view. One party of five were looking over a map and as they thought that Dawson appeared to be only a short distance away they made up their minds to reach it in 2 or 3 days.” In reality many of those who followed the Edmonton route to Dawson City spent up to three years on the trail. Even the best-equipped and most experienced adventurers took a minimum of fourteen months.

Would Shand and his fellow gold seekers have set out for Dawson City had they known how daunting the route actually was? It is difficult to say. One thing is certain, however, the maps Shand and his fellow prospectors carried to the Klondike were more representative of southern dreams than northern realities.