A Visual History of the Industrial Revolution

Exploring a trove of nineteenth-century engineering plans, blueprints, and drawings in Lowell, Massachusetts By Nicholas A. Basbanes Nicholas A. Basbanes recently received a National Endowment for the Humanities fellowship to work on his book on paper, which is forthcoming from Knopf. His most recent book is Editions & Impressions, a collection of essays. His other works include the acclaimed A Gentle Madness, Every Book Its Reader, Patience & Fortitude, Among the Gently Mad, and A Splendor of Letters.

Nicholas A. Basbanes recently received a National Endowment for the Humanities fellowship to work on his book on paper, which is forthcoming from Knopf. His most recent book is Editions & Impressions, a collection of essays. His other works include the acclaimed A Gentle Madness, Every Book Its Reader, Patience & Fortitude, Among the Gently Mad, and A Splendor of Letters.

As a boy growing up in Lowell, Massachusetts, in the early 1950s, it was accepted as an article of faith in the public schools I attended that the “Spindle City,” as it was known, was established in the 1820s as the world’s first planned industrial community, all of it made possible by the surreptitious introduction of technology into the United States at a time when England fiercely protected its manufacturing secrets.

Beginning in the early 1780s, it was a criminal offense to export any piece of industrial equipment outside of Britain and Ireland, and any technical information that might assist in replicating or improving it. Artisans and craftsmen who operated the machines were forbidden to leave as well. No plans of any sort could be copied, no notes sketched out of any kind, and certainly no three-dimensional models made, however crude they might have been.

While traveling abroad with his family between 1810 and 1812, the Boston merchant Francis Cabot Lowell, a brilliant son of privilege with impeccable letters of introduction was allowed to tour a number of textile mills in England and Scotland. Although his hosts were gracious in showing him around, it was understood that he could take no notes, especially of the power looms then being used to weave cotton yarn into finished cloth. To insure that no secret drawings had been made, Lowell’s belongings were searched twice prior to debarking for America.

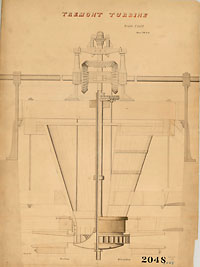

But gifted, apparently, with what we would today call a photographic memory, and a standout student of mathematics while at Harvard to boot, Lowell is believed to have sketched out the essence of what he saw during the voyage home. On his return, he engaged the services of Paul Moody, a “thorough, practical machinist,” according to one early account, with a knack for creative thinking who in time would introduce numerous innovations critical to the development of what were called “self-acting” machines, an early form of automation pioneered in the textile industry.

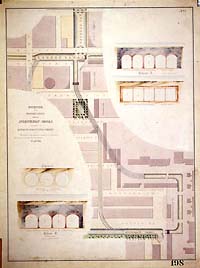

No record survives of how Lowell and Moody pooled their particular skills, but in very short order the collaboration had fashioned a system of water-driven power looms that attracted the financial backing of some wealthy Massachusetts entrepreneurs, brought together by the merchant Nathan Appleton. In a matter of months they converted a former paper mill on the Charles River in Waltham into the nation’s first vertically integrated textile manufacturing plant. By the end of 1814, the enterprise, called the Boston Manufacturing Company, was converting bales of ginned raw cotton into bolts of finished cloth in one sustained process.

By 1820, sales were a heady $260,658 a year, and for the four-year period between 1817 to 1821, dividends to stockholders averaged 19.25% a year, and reached a dizzying 27.5% in 1822. Eager to expand, but limited by insufficient waterpower in Waltham, the merchants turned their attention to East Chelmsford, a rural farming village twenty-five miles north of Boston on the Merrimack River. They would name their new community for Francis Cabot Lowell, who had died in 1817 at the age of forty-two, but whose “entirely new arrangement,” according to Nathan Appleton, had made possible “all the processes for the conversion of cotton into cloth, within the walls of the same building.”