Let Freedom Ring

A 19th-century British Naval Officer’s Journal Records the Price of Slavery

By David W. Pettus David Wingfield Pettus, former president of the National Maritime Park Association in San Francisco, has assembled a noted library of nautical fiction over many years of collecting, and often lectures on collecting at universities and libraries. A graduate of the University of California/Berkeley (B.A., History), he served in the U.S. Army and worked at Life magazine before starting a real estate investment business. He retired to pursue a writing career and is currently at work on a book about Gilbert Elliot’s journal.

David Wingfield Pettus, former president of the National Maritime Park Association in San Francisco, has assembled a noted library of nautical fiction over many years of collecting, and often lectures on collecting at universities and libraries. A graduate of the University of California/Berkeley (B.A., History), he served in the U.S. Army and worked at Life magazine before starting a real estate investment business. He retired to pursue a writing career and is currently at work on a book about Gilbert Elliot’s journal.

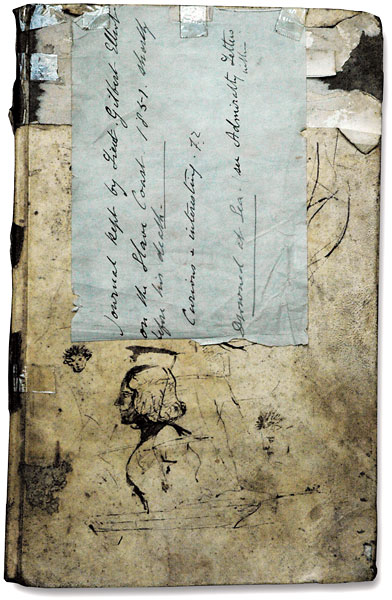

It was two a.m. in San Francisco on July 13, 2006, when I learned that the manuscript was mine. Despite unexpectedly spirited bidding at Sotheby’s in London, my agent had successfully acquired for me an important trove of nautical history, the 1851 Journal of Lt. Gilbert Elliot Jr., RN.

I’ve been collecting books of nautical subjects for many years. When one of my favorite book dealers here in California learned that this unique document was being offered for sale by the family—the first time the journal had ever been seen in public—he immediately called me. Naturally, I was interested, and we engaged an agent in London to inspect and authenticate the journal on which we intended to bid.

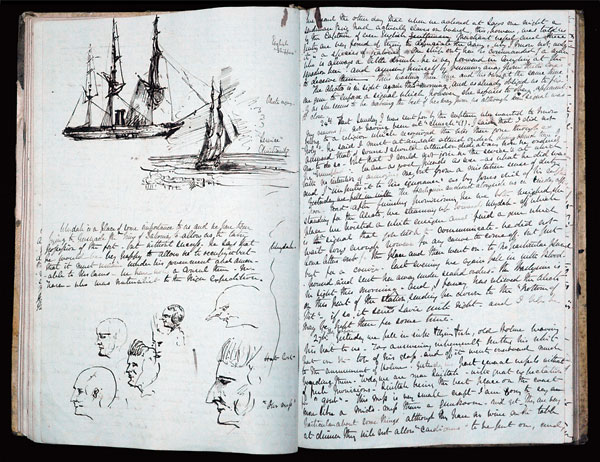

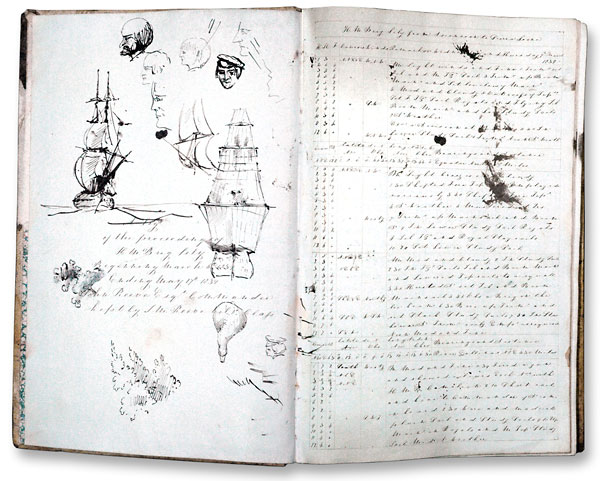

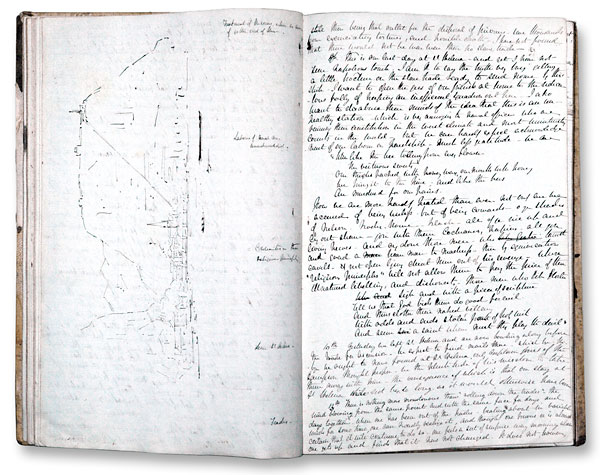

I was drawn to this remarkable volume for several reasons. First, illustrated log books are lovely artifacts in their own right. Additionally they have always been important source material for great literature of the sea. And in this case, the seaman’s pen-and-ink drawings, interwoven throughout the journal, looked to be excellent and particularly evocative. But most important, I was captivated by the idea of studying this young officer’s personal reflections on his mission: to stop the slave trade off the African coast.

Here was a British naval officer charged with overturning the pernicious institution his nation had—after much soul-searching—decided to eliminate from the civilized world, having outlawed slavery in their own country on 1807. Elliot’s journal, it seemed to me, was a vital link in understanding the moral crusade upon which the English people embarked—a mission that, in 1851, cost this young British naval officer and his whole crew their lives at sea.

The description from the Sotheby’s catalogue offered tantalizing quotes from the journal, noting that Elliot was a “confident, critical, and highly articulate” observer of life in the British navy, of West Africa in general and of the slave trade in particular; likely he would have published his journal had he made it home alive.

I was quite taken with this account and determined to acquire the journal and to write the full saga of this young man’s life as it exemplified this crusade by the British nation.

The auction lot included not only the journal—which Elliot had left aboard HMS “Sampson” when he left the ship—but also Elliot’s commission papers, along with letters from the British Admiralty to Elliot’s family, informing them of their son’s death. The bidding on auction day was, as I said, spirited. I feared I might be up against another individual collector with desire and resources to outstrip my own. In the end the other bidder turned out to be a major institution (I later discovered) with limitless desire, but not a matching purse.

I was simultaneously shocked and pleased when the hammer came down: shocked at the price [£16,800]; glad to have succeeded. I experienced, also, a sense of having committed myself to a project of singular importance.